Products You May Like

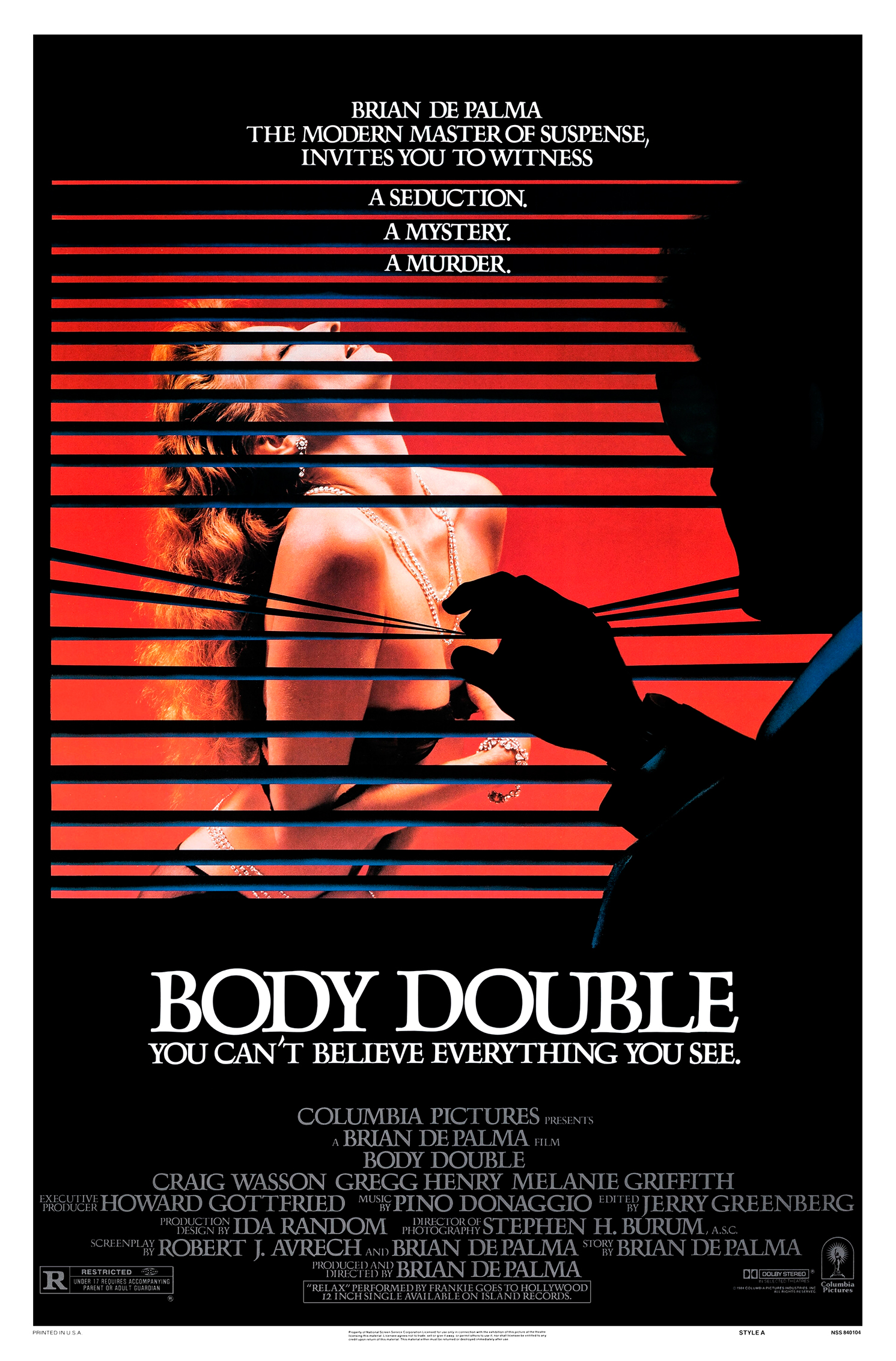

The art of the movie tagline is a slippery business. The right phrase can make the perfect tantalizing teaser, but the wrong words can undersell or even spoil the picture. Very few films have been so eloquently encapsulated as Brian De Palma’s Body Double, advertised with just six simple words: “You can’t believe everything you see.” First released in October 1984, it’s perhaps the director’s most provocative, contradictory box of tricks—implausible but irresistibly stylish, deceptively dumb while stealthily smart, wilfully sleazy yet wildly skillful.

By the early 1980s, De Palma had established a reputation as a talented but highly divisive figure. While the likes of Carrie (1976) and Dressed to Kill (1980) had succeeded at the box office, films like Phantom of the Paradise (1974) and Blow Out (1981) had struggled to find their audience. Further, his idiosyncratic blend of cine-literate suspense, bloody violence, and sharp satire left many cold; for every critic hailing his style and self-awareness, another was condemning him as a shallow misogynist, eternally copying Alfred Hitchcock.

His bluntly bombastic 1983 remake of the gangster story Scarface was widely perceived as a failure at the time, accused of excess in all areas. At first glance, the following year’s Body Double might seem a sheepish retreat into the traditional thriller territory that made his name. However, rather than reign in his controversial approach, the film attacks with a panache and insolence that makes few concessions to the unconverted.

From the start, Body Double plays games with the viewer. Rather than try to persuade us to suspend our disbelief, as most films do, it deliberately emphasizes the unreality of everything we see. It opens on a cheap movie set, replete with a neon sun, dry ice, and a tacky graveyard. As the camera roams, the credits begin, their font draining from red to white in an intentional parody of schlock horror film titles. The shot pans down to a coffin containing a glam-punk vampire, who abruptly breaks the fourth wall by turning and hissing into the camera.

Just as suddenly he freezes, and as fear twitches across his frozen features, we hear a director’s voice asking what’s gone wrong. The stricken bloodsucker is really an actor, Jake Scully (Craig Wasson), undergoing an attack of claustrophobia. As he’s led away by the crew, the fake sun accidentally catches fire, completing the illusion’s descent into total farce.

We then cut to a desert scene as our title finally appears—only for the image to be revealed as a painted backdrop being wheeled across a studio lot. We follow Jake as he ‘drives’ away from the set, filmed against a deliberately obvious and old-fashioned rear projection. Arriving home unexpectedly, Jake promptly finds that even his ‘real’ domestic bliss is false. Despite the cozy romantic photos that decorate the apartment, he catches his girlfriend Carol (Barbara Crampton) in bed with another man. Within just a few minutes the film has made clear that everything we see will be artificial, and the layers of deception only get more complex as we’re lured into a web of shifting identities, misleading performances, and seductive voyeurism.

The screenplay, written by Robert J. Avrech and De Palma, and based on the latter’s story, knowingly thumbs its nose at critics who’d lambasted the director as a manipulative Hitchcock clone. In a direct echo of Rear Window (1954), the newly idle Jake spies on his neighbor Gloria (Deborah Shelton), before realizing that foul play is afoot. Indeed, the initial premise almost promises a remake of Hitchcock’s film if only his work had centered its mystery on ‘Miss Torso’ (Georgine Darcy) rather than the less glamourous Thorwalds—a notion that suggests an extra touch of self-aware wit to the naming of De Palma’s movie.

As in Sisters (1972), Obsession (1976), and Dressed to Kill, De Palma draws on Hitchcock’s style and themes in order to create sly pyrotechnics that are entirely his own. If the initial scenes of Jake stalking Gloria nod towards Vertigo (1958), they soon build into an extraordinarily well-choreographed ballet once they reach the Rodeo Collection mall. Largely free of dialogue, and almost entirely carried by movement and Pino Donaggio’s opulent score, it’s a jaw-dropping tour-de-force, playing with geography and perspective. Stephen H. Burum’s stunning camerawork moves up and down and left to right, using every inch of the space while tightly controlling what it wants us to see.

Sometimes we know more than the characters (as when we see the ‘Indian’ or the security guard sneak by), and sometimes we’re left as shocked as Jake by a sudden reveal. It’s an astoundingly involving sequence, particularly considering that nothing especially dramatic happens. Admittedly, it draws on Hitchcock’s techniques, but even he was rarely so deliciously audacious in scale, nor so fearless in displaying his own mischievous sleight of hand.

Most controversially, the mall scene and indeed the first half of the film revolve around a man spying on an attractive, troubled woman. Rather than play the scenes subtly, De Palma amps up the slick eroticism to cartoonish levels, as if determined to enrage those who’d considered Dressed To Kill too leering and sexist. Of course, the most implausible and overtly sexualized moments are when Jake watches ‘Gloria’ dance at her window, and these are later revealed not to be her at all. However, it’s left for the viewer to decide whether these deceptive performances by adult actress Holly Body (Melanie Griffith) are a comment on the ludicrousness of straight male fantasies, or whether they’re simply a further example of the unrepentant male gaze in cinema.

Certainly, while she has a broadly similar character arc, Shelton’s Gloria remains passive and underdeveloped compared to Angie Dickinson’s Kate in Dressed to Kill, and the scene in which she kisses Jake despite knowing he’s been following her is ridiculously unlikely (if typically stylish). Likewise, although De Palma has always denied it was intentional, Gloria’s death by drill at the hands of her estranged husband has distinctly phallic overtones, as if designed to enrage feminist critics.

Yet judging these moments in isolation overlooks their context and the deliberate contradictions that run throughout the film. If Gloria’s murder is both horrifying and exploitative (a dichotomy at the heart of all horror cinema), her killer is never portrayed as anything but repugnant. Sam Bouchard (Gregg Henry) exudes arrogance, full of untrustworthy bonhomie and casual misogyny as he ensnares the meek Jake in his schemes. His contempt for others is made chillingly clear by the shot of him standing over Gloria’s body, hands on the drill and foot on her throat, his ‘Indian’ disguise adding blithe racism to his repulsively entitled characteristics.

Further, to suggest that the murder fits with the perceived slasher trope of “punishing” sexually active women is to overlook who replaces the deceased as the new female lead. Like Liz (Nancy Allen) taking Kate’s narrative place in Dressed to Kill, the second half of Body Double belongs to Holly Body—an assertive, strong, and sexually uninhibited woman rather than the traditional virginal ‘good’ girl.

While De Palma plays with puritanical audience expectations, he seems to delight in confounding them. Whether the role of a forthright adult film star is progressive or just more male fantasy is debatable, but it certainly suggests that the director’s world is more complex than the conservative standard attributed to certain slashers. (The fact that he had already spoofed the genre at the start of Blow Out and appears to reference Amy Jones’ 1982 The Slumber Party Massacre with Sam’s choice of murder weapon further implies a playful awareness of the pleasures and limitations of the form.)

Perhaps the most provocative and confrontational aspect of Body Double is the way its games implicate us as viewers. De Palma knows that voyeurism is the essence of cinema, and the more transgressive the sights, the better. Like Jake spying on Gloria/Holly from the dark of his apartment, we know we should look away—but we can’t. It’s no accident that the prominent line of dialogue during the porno movie shoot within the film is “I like to watch”. Nor is it a coincidence that just before showing Jake the telescope that sets the plot in motion, Sam proposes a toast “to Hollywood”.

Indeed, the film’s gleefully tawdry thriller plot is arguably a trojan horse disguising a caustically witty commentary on the dreams and disappointments of Tinsel Town. It emphasizes the tedium and hard work of trying to make it: enduring hostile auditions, attending pretentious acting classes, and surviving the trials and tribulations of cheap B movies like the opening sequence’s Vampire’s Kiss. The film is littered with L.A. landmarks, from the Capitol Records Building and Tail O’ The Pup to the Chemosphere that serves as the location for Jake’s adopted home. By locating its violent climax at the L.A. Aqueduct Cascades, it places the sex, danger, and illusion of the plot on an equal footing with the water supply, as though all these elements are essential to the city.

During the finale, Sam tauntingly portrays himself as a tyrannical director, scolding Jake for overplaying his part and ruining his “surprise ending”. Earlier, we see him in his “Indian” disguise supposedly fixing a satellite dish while Jake watches Gloria/Holly, a visual metaphor for the way he (and De Palma himself) will control which images are broadcast within the film, and to whom. His choice of secret identity could even be interpreted as a barbed comment on the self-serving myths historically promoted by American cinema, playing up the supposed “savagery of the disenfranchised to cover up the crimes of the conquerors.

Most pungently, Body Double blurs the lines between Hollywood and the adult film industry, skewering the pretensions of both. An enraged porn star proclaims that he’s “not some fucking stunt cock, I’m an actor!”, while adverts praise the salacious Holly Does Hollywood as “the Gone With the Wind of adult films.” Likewise, when Jake asks for motivational detail during his porn audition, the disgusted producer retorts “What are you, some kind of method actor?” and his ignorance of cum shots leads to the rebuke that they’re not making Last Tango in Paris.

The jaw-droppingly metatextual porno movie sequence even throws in a Norma Desmond lookalike alongside Frankie Goes To Hollywood and gallons of sex club schtick, tipping an insolent wink to Billy Wilder’s classic Sunset Boulevard (1950) while utilizing every ounce of cinematic skill to portray the sleaziest possible style of film. Pleasingly, De Palma doesn’t exclude himself from the mockery. When Jake goes to Tower Records to rent pornography, a woman can be heard in the background asking for his Carrie, as if both films are equally disreputable. Similarly, real-life adult actress Linda Shaw’s confusion of the word exhibitionist for “expositionist” makes a wittily self-aware comment on Body Double itself—a feast of directorial exhibitionism held together by wildly improbable exposition.

As one character observes, “Acting is acting, right?” and Jake’s story is really the saga of him learning how to fake-it-til-you-make-it, a skill embodied by the more worldly Holly. Tellingly, the vampire outfit Jake sports during the abortive opening sequence is echoed by the studded dog collar and black leather later worn by Holly. The difference between them is that she wears it with the star-making confidence that he lacks until the film comes full circle for its cheeky end credits. Like Ti West’s MaXXXine (2024), the film simultaneously embraces and satirizes notions of the sinfulness and corruption of L.A. show business, sharing unapologetically ambitious female leads and a cheerfully cynical affection for the superficial sparkle of celebrity and success.

Perhaps inevitably for such a multi-layered, sharp-clawed, and sexualized film, Body Double received a distinctly mixed reception on release and remains divisive 40 years later. Its influence has crept into the mainstream from time to time, for example in Paul Verhoeven’s aggressively blunt Basic Instinct or certain aspects of Robert Altman’s lauded but far more comfortable Hollywood satire The Player (both 1992). Ultimately however it stands alone: a lovingly written poison-pen letter to film itself, and a deliberately thorny celebration of our compulsive need to watch.

Categorized:Editorials