Products You May Like

The mysterious, sudden abandonment of the ancient lost city of Cahokia by its inhabitants has been puzzling historians for a long time now – and experts have cast fresh doubt on one of the most popular theories to date.

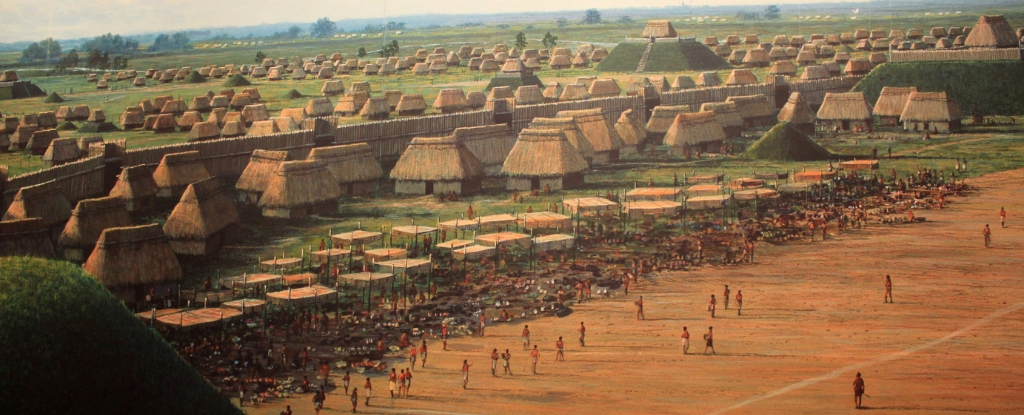

For several hundred prosperous years, Cahokia was the place to be in what is now the US state of Illinois.

Around the middle of the 14th century, the 50,000 or so people who called the bustling, vibrant city home departed for other places, suggesting that something pretty dramatic and life-changing had taken place.

One explanation for this mass exodus has blamed a severe drought followed by widespread crop failure – but a new investigation from the US Bureau of Land Management and Washington University in St. Louis suggests otherwise.

“Given the diversity of their known food-base, the domesticated landscape around Cahokia may have been resilient in the face of climate change and capable of producing more food than was required by Cahokians,” write the researchers in their published paper.

Cahokia was located across the Mississippi River from today’s St. Louis, Missouri, and was likely once the largest North American city north of Mexico. When Europeans arrived, they found huge earthen mounds as evidence of settlement – including Monks Mound, one of the largest prehistoric earthworks of its type.

Here, the research team analyzed soil samples taken deep underground, looking for carbon isotopes (left behind atoms) that act as indicators for the types of crops being planted across the centuries.

Different plants leave different carbon signatures, and the researchers were able to work out that two particular carbon isotopes – Carbon-12 and Carbon-13 – stayed fairly consistent across the period when people were leaving Cahokia. That suggests that drought and crop failure weren’t what was happening.

“We saw no evidence that prairie grasses were taking over, which we would expect in a scenario where widespread crop failure was occurring,” says archaeologist Natalie Mueller, from Washington University in St. Louis.

Mueller and fellow archaeologist Caitlin Rankin suggest that the enterprising Cahokians were likely to be able to adapt to droughts that came their way, while also pointing out that such a sophisticated society probably had food storage systems in place.

Next, the researchers want to do more work to get a picture of crop patterns over a broader region, as well as run tests on the crops these ancient people would have used, to see exactly how they hold up to drought conditions.

Gathering that information would help us see if people switched to different crops in response to climate change,” says Mueller.

However, while these soil samples give us clues about what didn’t happen, they don’t really tell us what did happen. The authors of this study think it may have been a more gradual process than we thought, with a lot of contributing factors.

“They put a lot of effort into building these mounds, but there were probably external pressures that caused them to leave,” says Rankin. “The picture is likely complicated.”

The research has been published in The Holocene.