Products You May Like

We take the internet for granted sometimes, and I say this as someone who had access to the internet for most of my teen years. I grew up before social media, for which I am deeply grateful, but I still had access to Instant Messenger, to chat rooms, to burgeoning websites with forums from my favorite teen magazines, and to message boards galore. These were tremendous resources for getting advice and insight about any and everything, from how to write a good paper or speech, to how to navigate a tricky friendship/romantic connection, to getting to know my anatomy, and so much more.

Now, that information is even more abundant. Not all of it is great or accurate, of course. But there are also more safeguards in place and more professionals working to vet these resources for the strongest and most accurate advice and insight.

But what did teenagers do before the advent of the internet? Certainly, they talked with one another — I suspect, like me, young people got their information about what certain slang terms meant from more worldly friends. They also probably talked to parents or other trusted adults. But there are some topics that aren’t easy to seek advice about from those resources.

In researching the history of Maureen Daly’s Seventeenth Summer, one of the things that stuck with me was how Daly had a robust career as an advice columnist for teenagers. She wrote “On The Solid Side” for The Chicago Tribune, which was syndicated across the country. It offered advice on everything from romance to navigating arguments with parents and more. The columns covered everything from what happens if you tell an off-color joke (see image), how to lose weight if you’re a little too droopy (directed, of course, at young female readers), and why it’s important not to stand up a date (ghosting is not a new phenomenon). Columns like Daly’s, as well as her historically important books for teens, were important because they were foundational in acknowledging teenagers, and specifically white middle class cisgender teenagers, as a demographic socially, culturally, and economically.

It’s not a surprise teen advice book were among the first nonfiction titles written, marketed, and sold to teens — an early forerunner of YA nonfiction more broadly. They sought to encourage white middle class cis teens to be their best selves and to conform to social standards that would ensure their place in “proper” white society as they aged into adulthood. Many, including the recently revisited and re-popularized Glamour Guide for Teens by Betty Cornell, featured or were influenced by the teen celebrities or advice offered in magazines geared to teenagers at the time.

But what were some of these books? How have they aged? What do they have to say about the time and context in which they were written?

Cornell’s book, published in 1951, offered advice on beauty, health, fashion, manners, and more, all courtesy of Betty Cornell, who was a teen model of the 1940s. She was well known for having been extremely thin — the Toledo Blade in 1947 noted her 19 inch waist — but, as she shares in the beginning of Glamour Guide, she didn’t start out that way and indeed, had to work hard to change from “tubby teen” to her svelte figure.

If Cornell’s name or book sound familiar, you may be remembering that her book was used as inspiration for 2014’s award-winning YA nonfiction memoir Popular: Vintage Wisdom for a Modern Geek by Maya van Wagenen. Van Wagenen’s father found a copy of Cornell’s book and bought it for her, and she followed the advice in the book as she navigated middle school.

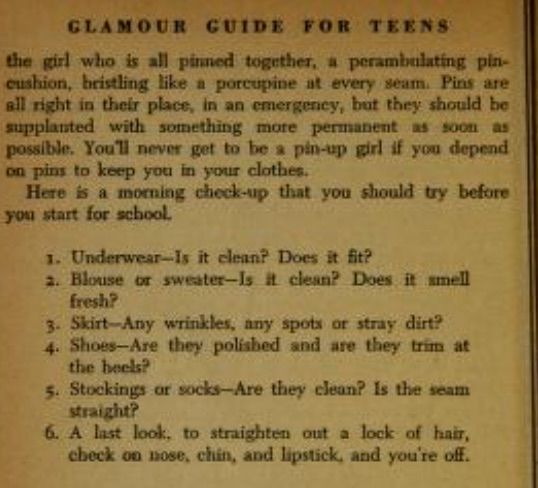

“Beautiful hair is one of the most important things a girl has,” writes Cornell in her book. “Whether it be blond, brunette or red, pretty hair can always overcome the handicap of a not-so-pretty face.” In order for hair to be healthy, she continues in the book’s fourth chapter, it begins with a good diet and exercise, the central topics of the first three chapters of the book. Ever wondered about the wisdom of brushing one’s hair 100 times before bed (see this iconic scene in Now and Then — Chrissy’s mom would have grown up on Glamour Guide); you can thank Cornell for codifying it in her advice book.

Though not necessary to match, do note that when selecting nail polish, it should harmonize with whatever lipstick you wear frequently. The best method for walking to appear graceful and model-like is moving your leg in a singular motion from the hip, working to avoid bending your knees as much as possible. Make sure you always smell nice, too, as one of the best compliments a person can receive is just that. Likewise, underarms are sleeker and more dainty when they’ve been shaved.

But what of behavior? Of dating? Cornell covers those topics, too.

Money is, of course, a teen concern, and mom and dad can’t always provide enough for one’s busy life. Cornell suggests teens think hard about finding a steady job but not at the expense of school and dating. She lays out a sample schedule for babysitting, saying, “there is nothing to prevent you from making up a list of clients and keeping in touch with them.” That schedule not only includes nights of the week and families of which you’d babysit, but also space for a free Thursday evening, free Friday evening, and Saturday night, “free for dates.” Another great job idea? Cooking. It’s as simple as being able to “canvas your block and notify everyone that you will make cakes, cookies, hot rolls, etc., for any parties they are planning.”

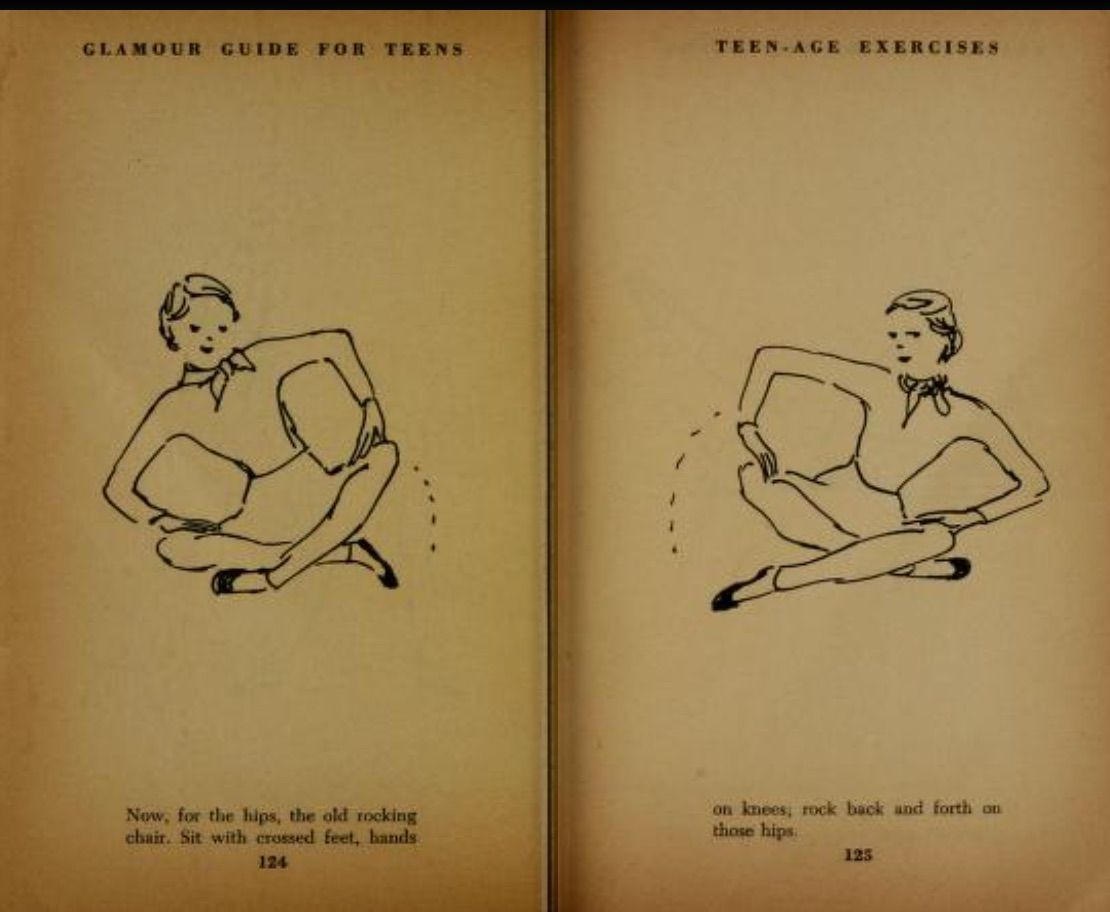

Don’t have a lot of friends or party invites? It could be your own personality being a drag and it’s time to get real about it. Likable people avoid bigotry, and they also avoid blackballing, “a nasty word [. . . that] even tastes bad on the tongue.” And if popularity is on the mind, never fear: the best way to become popular is to be yourself, be kind, and be a leader. You’ll do that by looking good and feeling good, too, and Cornell provides some very basic physical movements immediately after the chapter on popularity to help you along the way.

Cornell’s book has been fascinating for so many readers for so many years. Its depiction of a “purer” time when a girl had little more to worry about than being pretty and liked and that there’s a handy guide for solving this issues might be a big reason. But nostalgia overlooks the more critical role these books played: they created and maintained white, middle class norms, passing down appropriate ways to be and to act that were crafted for middle class white readers — note the models in the book were all white, and when it comes to discussions of beauty, there is no white default, as white is the only option. Is there comfort, maybe, in thinking that culturally, we’re a bit broader? That advice books like these have better embraced a multicultural world?

Maybe, maybe not. If anything, we see what stood as “feminist” at the time has certainly become far more cringe-worthy than empowering. That could even be said of van Wagenen may view the book now, eight years after its publication and post–high school graduation, as (white) young adults have become more attuned to their privileged status.

There’s also the ever-broadening internet, which has allowed those of the global majority to speak up more, to deconstruct white culture and its assumed role as “norm,” and given opportunity to create more spaces for young people to discover their true selves and embrace it — nail shades in a coordinating lipstick or not.

Cornell’s books, which included several additional advice titles, weren’t the only midcentury titles reaching and creating a specific brand of white middle class attitudes and behaviors.

Let’s step back for a second to a familiar name.

In 1946, just four years after the publication of her sister’s popular Seventeenth Summer, Sheila John Daly published a teen advice book as a teenager herself. Older sister Maureen, who’d found success with “On The Solid Side,” passed down the column to Sheila. She had the voice and know-how, of course, being the target demographic herself.

Sheila published Personality Plus only a couple of years after “teen-ager” became a common term used to describe adolescents (and Maureen’s book likely had a hand in making that term popular). It’s not condescending nor pandering, and there’s just enough snark and humor in its pages to give it an authentic feel. In appealing to its readership, Daly peppers the book with references to current pop culture stars and teen idols. Though there’s not a full text available to peruse online, you can read some great lines here, and know that the book must have done well, as Sheila wrote several more teen advice books, including What’s Your P.Q. (Personality Quotient), Party Fun, and Pretty, Please.

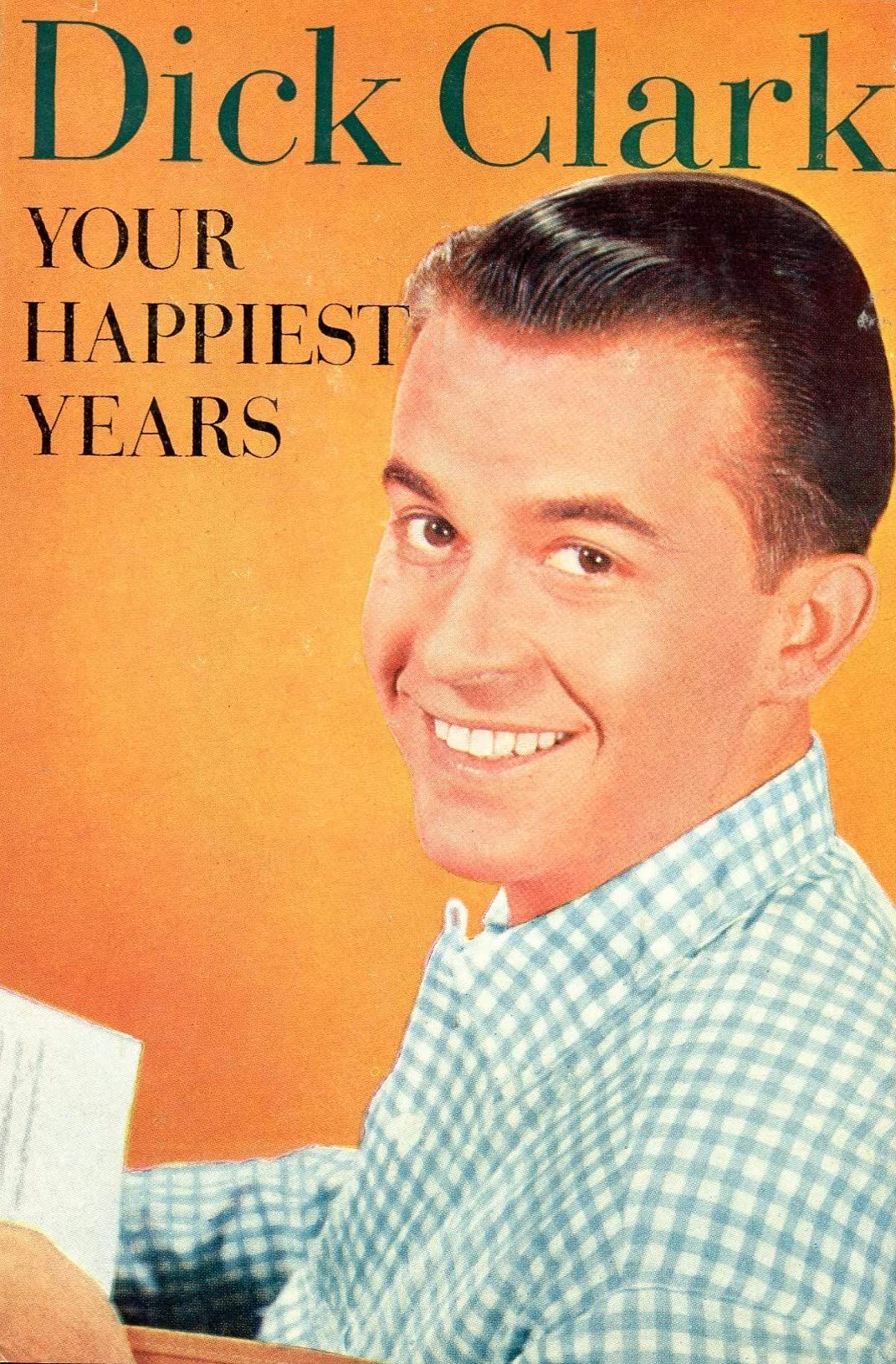

Maybe it’s not surprising that celebrity helped encourage — or sought to emulate — the success of teen advice books. Cornell, as noted, was a model. But she wasn’t the only star writing wisdom for teens. So, too, did Dick Clark in his 1959 Your Happiest Years. Yes, that Dick Clark.

It’s not known whether Clark penned the advice or not, but given the popularity of American Bandstand, which debuted in 1957, his name was enough.

“Teenager,” popularized in the decade before, exploded in use and in the consciousness after World War II, specifically in America. Jon Savage wrote about this extensively in his book Teenage: The Creation of Youth 1875–1945, and one of the themes he explores is the use of the term less as an understanding of a specific age group (like “adolescence”) and more as a marketing category. Clark’s book? It fits directly into this idea, given that teenagers were able to spend their own money (earned through their babysitting or cooking jobs or even those rare “part-time” jobs Cornell cites) and do so on items that met their demands and interests. We see this teenager-as-marketing-idea play out still today, with even how young adult books are categorized and the debate around whether it’s an actual category of books or simply a way to sell certain stories.

Despite the title, Clark’s advice in the book was anything but happy. Where Cornell praised the use of makeup for teens, Clark warned against it. But more, it offered a preview of what teen readers would see echoed in the YA problem novels of the next decades. In one anecdote, Clark recalls the time a girl he knew crashed his car and became injured because she decided to stay the night at a friend’s house without informing him. A boy who had a history of illness didn’t adhere to curfew and came down with tuberculosis.

Girls should observe how their mothers treat their fathers after a long, hard day at work — prepare the meal, of course — and boys should be careful not to spend their money frivolously so as to ensure they have the funds for dating in the future.

Even a major influence on teens knew his job was to reinforce white, middle class, heteronormative standards.

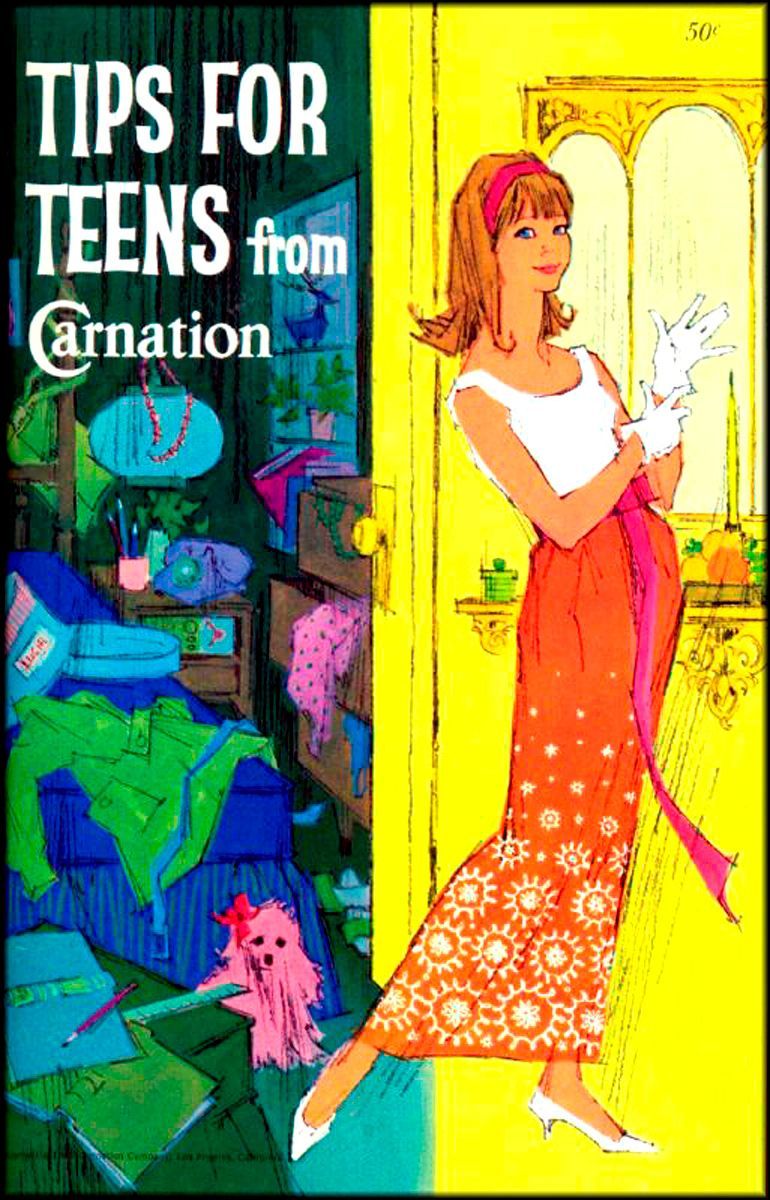

If we take Savage’s argument that teenager was a marketing term, it’s impossible not to then look at yet another teen advice book of the mid-1960s: Tips for Teens from Carnation. Carnation, as in the Nestle brand best known for its condensed milk.

“A bored girl isn’t a pretty girl. Chances are she’s doleful, droopy, dull, and drearily uninteresting and very little fun,” reads a paragraph from the section on breakfast ideas. Ostensibly a cookbook shilling Carnation products, the guide is much bigger than that. It, too, offers white cis het norms to teens in order to not only teach them to conform, but to also consume and that consumption is key to being the best version of yourself possible.

Who can be dull when you could be buying condensed (white) milk?

These are not, of course, the only teen advice books from this 1940s to late 1960s era that are worthy of exploring and deconstructing. But they each highlight what drove their popularity and how it is we’ve found far more wide ranging teen advice books and websites today. No longer are these types of books only serving one purpose. They can’t — and though there certainly are books for teens that prescribe white norms, they’re in small, specialized markets (including those that are, no surprise, funding some of today’s biggest book challenges across the country).

Check out some of the following for even more curious, humorous, and cringe-worthy advice. Many may be available in the public domain or via Google Books and the Internet Archive, as they can be tough to track down via traditional retailers (and fun fact: the rise in popularity of Cornell’s Glamour Guide following the publication of Popular led to resellers and antique book collectors and sellers trying to figure out what, exactly, was causing those books to become high demand):

- Charm is Not Enough by Mary Young (…marry young?)

- The Co-Ed Book of Charm and Beauty by the Co-Ed editors (Co-Ed was a home economics focused magazine published by Scholastic for young people)

- Etiquette for Young Moderns by Gay Head

- For Every Young Heart by Connie Francis (she was involved in American Bandstand, too)

- Hi There, High School by Gay Head

- Once Upon a Dream: A Personal Chat with All Teenagers by Patti Page

- The Seventeen Book of Young Living by Enid Haupt

- She-Manners by Robert H. Loeb Jr. (girls, don’t ever wear shorts…)

- Teen Talk by Marion Glendining

- That Freshman Feeling by Judith Unger Scott

- Your Manners Are Showing by Betty Betz

Want another deep dive into vintage teen reads? Dig into this look at 1950s teen pulp comics.