Products You May Like

On someone’s desk, one of the little gray cubes wouldn’t raise an eyebrow. To the untrained eye, they look like paperweights.

“Marie Curie‘s granddaughter has one. She uses it as a doorstop,” Miriam Hiebert, a historian and materials scientist, told Insider.

The weight of the 2-inch (5 cm) objects might be surprising, though – each is about 5 pounds (2 kg). That’s because they’re made of the heaviest element on Earth: uranium.

The cubes were once part of experimental nuclear reactors the Nazis designed during World War II. As far as researchers know, only 14 cubes remain in the world, out of more than 1,000 used in Nazi Germany’s experiments with nuclear weapons.

Over 600 were captured and brought back to the US in the 40s. But even after that, what happened to most of the cubes is still unclear.

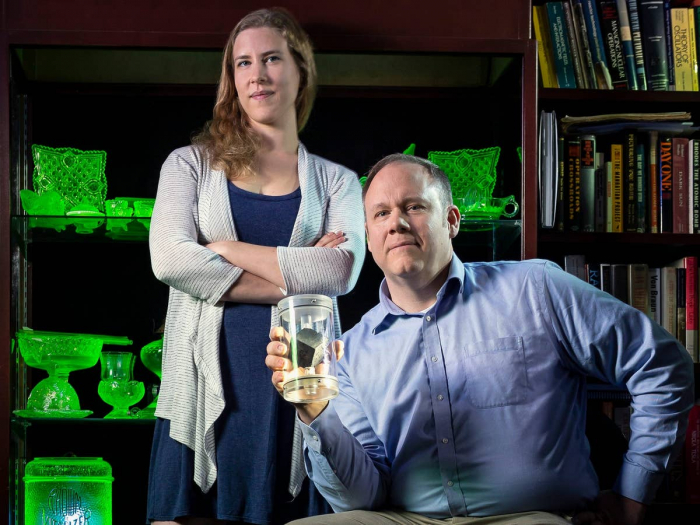

Hiebert and Timothy Koeth, a professor of material science and engineering at the University of Maryland, are writing a book about the cubes. After years of research, they told Insider they think they know what happened.

Miriam Hiebert and Timothy Koeth. (John T. Consoli/UMD)

Miriam Hiebert and Timothy Koeth. (John T. Consoli/UMD)

Small cubes with a long history

Koeth describes the cubes as “the only living relic” of Nazi Germany’s nuclear effort.

“They are the motivation for the entire Manhattan project,” he said.

Leading up to the war, Germany was a world leader in physics, and the science of nuclear energy was in its infancy. In 1938, German chemist Otto Hahn revealed that he’d created fission by blasting neutrons at a uranium core.

Scientists fleeing Europe, including Albert Einstein and Enrico Fermi, alerted the US that Germany could develop an atomic bomb. The arms race was on.

In its natural form, uranium is not very radioactive. So the cubes aren’t very dangerous. But apply a neutron to uranium, specifically the isotope U-235, and it cracks open “like a piñata,” as Koeth put it.

“You smash it open with a neutron, and new elements come out, and also more neutrons,” he said.

To create an explosion, this must happen in a chain reaction: The neutron gets captured by another uranium atom, which splits open, creating more neutrons, and so on. To make that possible, the neutrons need to get slowed down by a substance called a moderator.

The US used graphite for that, and it worked. Scientists with the Manhattan Project created a self-sustaining nuclear chain reaction in December 1942. But the leaders of Nazi Germany’s nuclear program, Werner Heisenberg and Kurt Diebner, picked heavy water as their moderator: water in which the hydrogen atoms are replaced with deuterium. Cubes of uranium would be dipped into the water.

The Nazis developed two prototype reactors, the larger of which had 664 uranium cubes strung from a plate and suspended over a pit of heavy water. The smaller reactor used about 400 cubes.

The “Alsos” mission

The Allied forces didn’t know how far along the Nazi nuclear program was. And they were nervous.

So in 1943, the Allies launched a secret mission – the codename was “Alsos” – to find out. A team of about a dozen people, including soldiers, scientists, and interpreters, traveled through Italy, France, and Germany searching for traces of the Nazis’ nuclear experiments. Then as the war neared its end, the mission’s objective shifted to making sure nuclear material (or scientists) wouldn’t make it into the hands of the Soviets.

In April 1945, Allied forces found and captured about 1.6 tons of uranium cubes in southern Germany. Heisenberg, his team, and the larger of Germany’s two reactors – neither of which ever worked – had previously been hiding there. Nearly all the cubes were sent back to the US. The Alsos mission never found the smaller reactor.

Alsos intelligence officers after locating German uranium cubes, Haigerloch, Germany. (Samuel Goudsmit/AIP Emilio Segrè Visual Archives)

Alsos intelligence officers after locating German uranium cubes, Haigerloch, Germany. (Samuel Goudsmit/AIP Emilio Segrè Visual Archives)

Cubes were picked off the pile

After the cubes arrived in the US, Hiebert said, their trail went cold. The US was highly secretive about its own nuclear program, so there aren’t many public records about the Nazi uranium.

“We currently know of 14, out of almost 1,000 that existed in total,” she said, “so most of them are still unaccounted for.”

But those 14 offer clues about what may have happened to the rest.

Koeth, who has been an avid collector of nuclear objects since his early teens, has two of the 14. Both were given to him by colleagues. The first was a birthday present about a decade ago, but the giver asked to remain anonymous and Koeth won’t reveal how they got the cube.

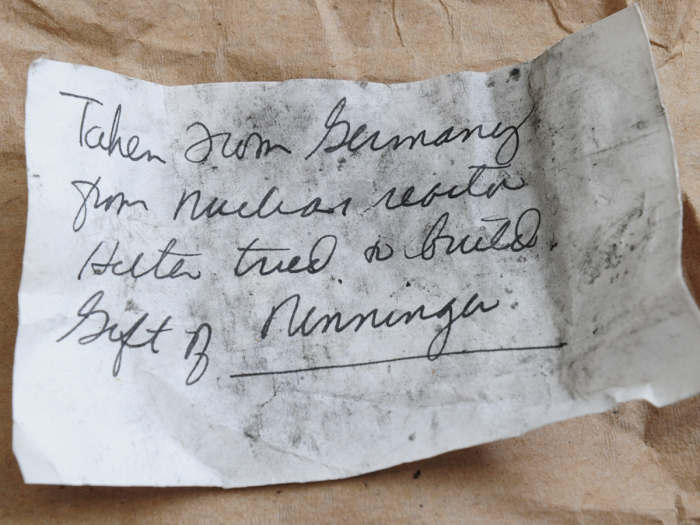

It came with a handwritten note that read: “Taken from Germany from nuclear reactor Hitler tried to build. Gift of Ninninger.”

The note that accompanied Koeth’s cube. (Timothy Koeth)

The note that accompanied Koeth’s cube. (Timothy Koeth)

Robert D. Nininger, it turns out (his name has just one n), was a geologist for the US Atomic Energy Commission in the 50s. Koeth and Hiebert found documents that show he worked with the Manhattan Project. Geologists with the project had the difficult job of sourcing uranium.

“Just figuring out where to get it from was a huge task,” Hiebert said.

Koeth’s other cube came from a former faculty member at the University of Maryland, who in turn had gotten it from another faculty member, Dick Duffey. During the war, Duffey, a chemical engineer, had worked at a plant in Beverly, Massachusetts, that processed scrap uranium, Koeth said.

Based on these findings and others, Hiebert and Koeth think most of the Nazi cubes that made it to the US were repurposed and used in America’s own nuclear program. But some, they think, got “picked off the pile” and kept as souvenirs.

As for the 400 cubes from the second reactor, Hiebert and Koeth found some documents suggesting they were sold on the black market to what became the USSR.

From a nuclear reactor to counter-proliferation efforts

The Pacific Northwest National Laboratory owns another one of the Nazi cubes but doesn’t have records documenting its history.

So two scientists there, Jon Schwantes and Brittany Robertson, recently figured out a new way to date the cube – and other uranium products – more precisely than was previously possible. To do so, they measured the levels of two atoms, protactinium and thorium, that accumulate over time as uranium decays.

In a presentation last month at the annual meeting of the American Chemical Society, Schwantes and Robertson revealed that when they applied the method to their lab’s cube, the results put it squarely in the expected age range – it dates back to the years Nazi Germany was developing nuclear weapons.

Today, though, the cube has a different function: “The primary purpose it is used for is training,” Schwantes told Insider.

The national laboratory teaches security personnel how to recognize nuclear and radioactive material on sight. So the cube offers a good training example.

“I find that really kind of an interesting storyline for this cube – that it was first produced for somebody’s nuclear program, and now it’s being used for nuclear nonproliferation,” Schwantes said.

This article was originally published by Business Insider.

More from Business Insider: