Products You May Like

Scientists are continually discovering more about how we pick up language from the earliest ages, and a new study looks specifically at how very young children integrate different sources of information to learn new words.

Those sources can be everything from whether or not they’ve seen an object before (which points to whether or not it has a name they’ve heard before) to what they might be chatting about with someone when a new word is introduced.

To figure out more about how these sources are combined, researchers put together a cognitive model, proposing a social inference approach where children use all the available information in front of them to infer the identity of a given object.

“You can think of this model as a little computer program,” says developmental psychologist Michael Henry Tessler from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). “We input children’s sensitivity to different information, which we measure in separate experiments, and then the program simulates what should happen if those information sources are combined in a rational way.”

“The model spits out predictions for what should happen in hypothetical new situations in which these information sources are all available.”

The theoretical system researchers developed was informed by previous research in philosophy, developmental psychology, and linguistics. Data were also gathered from tests carried out with 148 kids aged between 2-5 years old to assess their sensitivity to different sources of information. The data were then plugged into the model.

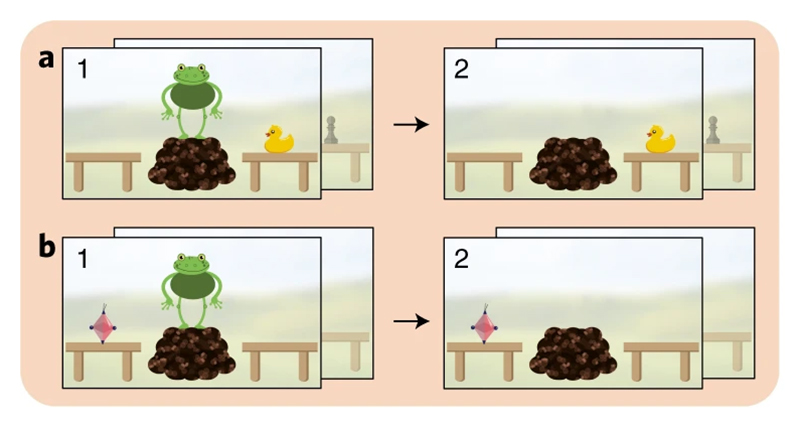

Having gathered predictions from their model, the researchers then ran real-world experiments with a total of 220 kids to see how they might infer the meaning of words such as duck, apple, and pawn, when the relevant objects were put in front of them on a tablet screen.

A variety of cues were given to the children about the relationships between words and objects, including a voiceover from a presenter and a mixture of labels that they would and wouldn’t have already been familiar with. In this way, the researchers could test three sources: previous knowledge, cues from the presenter, and context in a conversation.

Part of the word test app shown to children. (Frank et al, Nature Human Behaviour 2021)

Part of the word test app shown to children. (Frank et al, Nature Human Behaviour 2021)

The model approach lined up very closely with the results of the final experiments, suggesting that these three information sources are used by kids in predictable and measurable ways as they build up their vocabulary.

“The virtue of computational modeling is that you can articulate a range of alternative hypotheses – alternative models – with different internal wiring to test if other theories would make equally good or better predictions,” says Tessler.

The results presented in this study suggest that various alternative hypotheses can be discounted: that certain information sources are ignored, for example, or that the way sources are processed changes as children get older.

What the research gives us is a mathematical perspective for understanding how language learning happens in children, but it’s still early days for this particular approach; more studies are going to be needed with larger groups of kids to help develop the idea.

How we go from knowing a handful of words to knowing several thousand in just a few short years is fascinating stuff – and understanding more about how it works can inform everything from teaching to therapy.

“In the real world, children learn words in complex social settings in which more than just one type of information is available,” says developmental psychologist Manuel Bohn, from the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Germany.

“They have to use their knowledge of words while interacting with a speaker. Word learning always requires integrating multiple, different information sources.”

The research has been published in Nature Human Behaviour.