Products You May Like

Even predators can’t stay awake all the time. But sharks, those sleek hunters of the deep, don’t exactly advertise when they’re taking a power nap.

A strange behavior has given them up, though. Marine biologists have discovered that sharks ‘surf’ ocean currents in a conveyor belt configuration, allowing them to take turns resting.

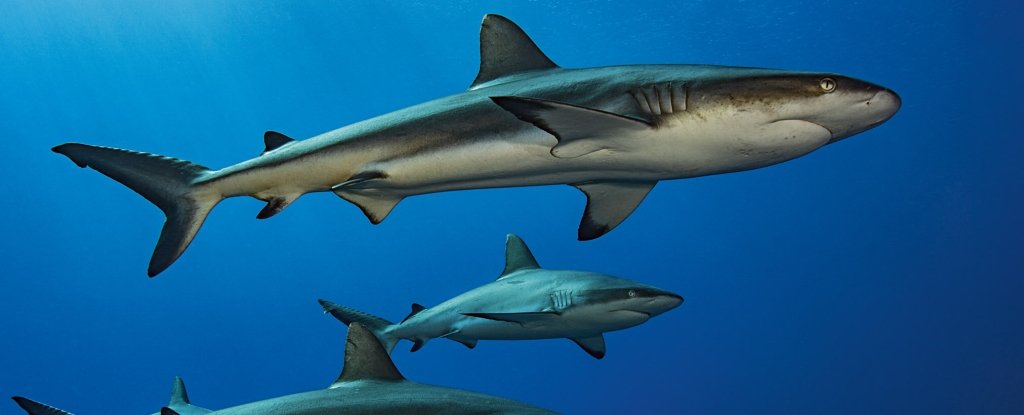

The revelation came when a research team led by Yannis Papastamatiou of Florida International University was studying the nocturnal hunting behavior of grey reef sharks (Carcharhinus amblyrhynchos) at Fakarava Atoll in French Polynesia.

These sharks never stop swimming for their entire lives. They need to keep moving in order to extract enough oxygen with their gills to keep them alive, so stationary resting, like the way other animals rest, is out of the question.

Exactly how sharks rest was a bit of a puzzle, until on a dive during the day, Papastamatiou noticed that the sharks were swimming against the updraft current in a certain channel. Even more interestingly, they were remarkably still, barely moving their fins or tails.

“During the day, they’re pretty placid and relaxed, swimming with minimal effort,” Papastamatiou explained. “It’s interesting because it’s a pretty strong current.”

As they crept forward to the front of the channel, the lead sharks would slip backwards, letting the current carry them back to the starting position. It was like some sort of strange conveyor belt – the sharks would inch forward against the current, be carried back, then inch forward again.

It was a phenomenon that was going to take a diverse toolkit to figure out. The team used a combination of acoustic tracking tags and underwater cameras mounted onto the sharks to track and observe the animals’ behavior when humans aren’t around. They also had their in-field observations of the sharks.

With these tools in hand, the researchers constructed a biomechanical model to calculate the energy expenditure of sharks swimming in these updraft currents.

Grey reef sharks literally live a life of ‘sink or swim’. With the current carrying them upwards, the sharks can relax a bit, keeping their muscle movements to a minimum. According to the team’s calculations, surfing the updraft allowed the sharks to conserve at least 15 percent of their normal swimming energy expenditure.

With this information in hand, the team realized they might be able to look for other shark resting spots, based on our current understanding of ocean currents. They used multibeam sonar to predict and map where updrafts might occur and used tracking sensors to monitor these spots.

With this monitoring data, the researchers were able to confirm that the sharks do indeed choose to hang out in updraft currents during the day, adapting their position to best minimize energy expenditure.

For instance, during incoming tides, which have stronger updrafts, the sharks group tightly together and display the conveyor belt shuttling behavior more strongly, and go deeper where the current is a little weaker.

During outgoing tides, which create more turbulence, the sharks are more spread out and hang out closer to the surface to avoid the roiling water below.

The behavior is similar to the way birds use updrafts to stay aloft with minimal energy expenditure, the researchers said. Future research may be able to use this information to locate sharks and other species, such as squids, that need to stay moving to stay alive.

“This study is a nice demonstration of energy seascapes, a spatial representation of how much energy it costs an animal to move through an environment,” Papastamatiou said.

“Marine environments are a lot more dynamic because of the water currents, which are much less predictable. They can change seasonally, throughout the day, and even minute by minute. Ultimately, the energy seascape helps explain why these animals are in this channel hanging out there during the day. Now we have an answer.”

The research has been published in the Journal of Animal Ecology.