Products You May Like

In the north of the Arabian Peninsula, bordering the Nefud Desert, archaeologists have recently catalogued vast stone monuments dating back 7,000 years. Shaped like long rectangles, the ‘mustatil‘ structures are a mystery – but new evidence suggests they were possibly used for ritual or social purposes.

Mustatils are amongst the earliest forms of large-scale stone structures, predating the Giza pyramids by thousands of years. Hundreds of these structures have been identified, and archaeologists believe they are somehow related to increasing territoriality as the once-lush region gave way to arid desert.

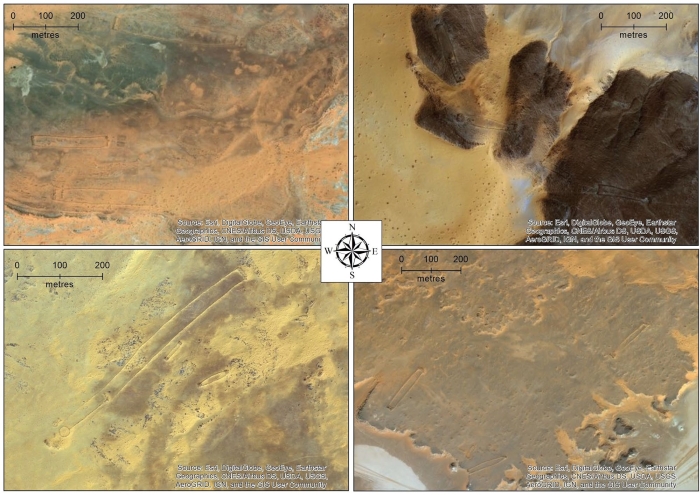

Discovery of the mustatils was first documented in 2017, enabled through satellite photography, which revealed the scale and number of these enigmatic structures in the desert lava field of Harrat Khaybar in Saudi Arabia.

Named ‘gates’ because of their appearance from the air, they were described as “two short, thick lines of heaped stones, roughly parallel, linked by two or more much longer and thinner walls.”

(Groucutt et al., The Holocene, 2020)

(Groucutt et al., The Holocene, 2020)

Now, a team of archaeologists led by Huw Groucutt of the Max Planck Institute for Chemical Ecology in Germany has conducted similar research. Studying satellite images of the southern edge of the Nefud Desert, they identified 104 new mustatils. Then they went out into the field and studied them up close.

Like the Harrat Khaybar mustatils, the Nefud Desert mustatils consist of two short, thick platforms, linked by low walls of much greater length measuring up to over 600 metres (2,000 feet), but never more than half a metre high (1.64 feet).

Similar construction methods can be seen in several mustatils: upright stones were placed vertically into the ground to form the basic shape of the wall, and rocks piled up to fill the gap between them, as seen in the image below. One structure yielded up charcoal, which dated the mustatil to 7,000 years ago.

(Groucutt et al., The Holocene, 2020)

(Groucutt et al., The Holocene, 2020)

This was an interesting time in the history of the region. It falls into the African Humid Period, which started around 14,600 to 14,500 years ago, and ended around 6,000 to 5,000 years ago.

During this time, the Sahara and the Arabian Peninsula had much more plentiful rainfall than they do today, and were much more green and lush.

But the period did not last as long on the Arabian Peninsula. A recent study suggests that the grasslands reached their peak expansion around 8,000 years ago, after which the region dried up very quickly, giving way to a landscape more like that we see today.

What the mustatils were actually used for, and why there are so many, is hard to gauge. But the researchers believe that the increased competition for resources and territory following the aridification could have played a role.

A careful study revealed that the long walls of the structures have no openings, and there was a curious dearth of archaeological artefacts, such as stone tools, in and around them. This suggests, the researchers believe, that the mustatils were unlikely to have been utilitarian, used for water storage, or corralling livestock, for example.

(Groucutt et al., The Holocene, 2020)

(Groucutt et al., The Holocene, 2020)

What their searches did turn up were assemblages of animal bones, including both wild animals and cattle or aurochs bones – although it’s unclear whether the latter were wild or domesticated. And one rock was found with a geometric pattern, pictured above. It was on the surface of an end platform inside one of the mustatils, where anyone standing inside could see it.

“Our interpretation of mustatils is that they are ritual sites, where groups of people met to perform some kind of currently unknown social activities,” Groucutt said. “Perhaps they were sites of animal sacrifices, or feasts.”

Another possibility is suggested by the close proximity of some of the structures. Perhaps, the researchers speculate, the purpose of the mustatils was the act of building them – a social bonding activity to increase community cooperation skills.

“The lack of obvious utilitarian functions for mustatils suggests a ritual interpretation. In fact, mustatils seemingly represent one of the earliest examples known anywhere of large-scale ritual behaviours encoded in the practice of monumental construction and use,” they wrote in their paper.

“Our findings indicate that mustatils, and particularly their platforms, are significant archives of Arabian prehistory, and their future investigation and excavation is likely to be highly rewarding, leading to a better understanding of social and cultural developments.”

The research has been published in The Holocene.