Products You May Like

A rare merger between clusters of galaxies has just revealed an even rarer sight. Astronomers have found a vast, low-frequency radio ‘bridge’ between the two, spanning a 6.5-million-light-year distance – evidence of a magnetic field connecting them in the early stage of the merging process.

It’s only the second time such a radio bridge has been identified between merging galaxy clusters. But already it’s providing some important clues as to how these bridges form.

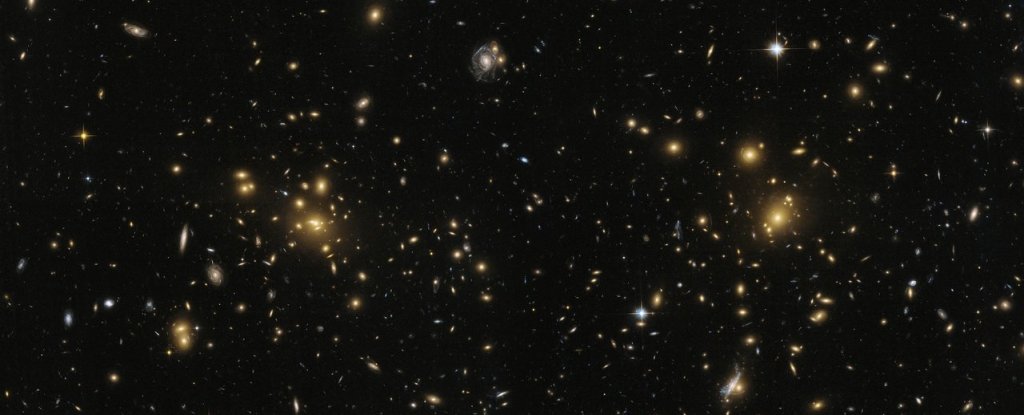

The galaxy clusters are around 3 billion light-years away, in a group called Abell 1758. All up, four clusters are involved in the impending smash-up – two massive cluster pairs coming together.

Last year, X-ray data revealed that the closely bound pair in the north segment, called Abell 1758N, has already moved together and separated, the cluster cores passing each other around 300 to 400 million years ago. They’ll swing back around eventually to come back together. The pair of clusters in the south, Abell 1758S, is still approaching each other for the first time.

Both of these pairs have a radio halo, thought to be generated by the acceleration of electrons in a merger event. And it’s these pairs that are separated by a distance of 6 million light-years, a gap that is slowly closing, for an eventual four-way cluster… bonk.

This scenario is very similar to the galaxy clusters Abell 0399 and Abell 0401, which last year became the first merging galaxy clusters revealed to have a low-frequency radio bridge connecting them.

Using the low-frequency radio telescope LOFAR, which consists of 25,000 antennas across 51 locations, astronomers detected a distinct radio emission at 140 megahertz.

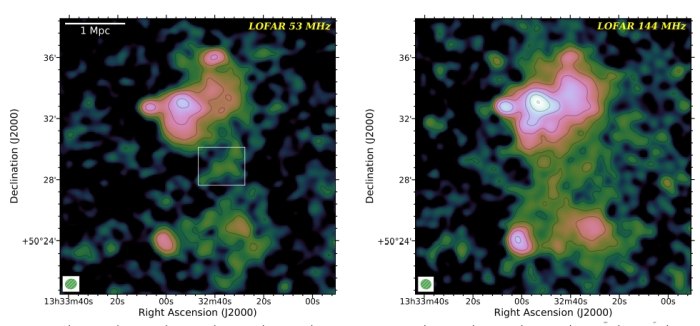

Now a team of astrophysicists led by Andrea Botteon of Leiden Observatory in the Netherlands has turned LOFAR to Abell 1758. At 144 megahertz, they discovered radio emission stretching between A1758N and A1758S, just like the radio bridge between Abell 0399 and Abell 0401.

(Botteon et al., MNRAS, 2020)

(Botteon et al., MNRAS, 2020)

“We confirm,” they wrote in their paper, “the presence of a giant bridge of radio emission connecting the two systems that was reported only tentatively in our earlier work. This is the second large-scale radio bridge observed to date in a cluster pair. The bridge is clearly visible in the LOFAR image at 144 MHz and tentatively detected at 53 MHz.”

This emission is interpreted as evidence of a vast magnetic field connecting the two clusters. If this magnetic field acts as a synchrotron (particle accelerator), electrons should be accelerated along it to relativistic velocities, producing synchrotron radiation detectable as a low-frequency radio glow.

But there’s another possible explanation – Fermi acceleration, in which electrons interacting with turbulence and astrophysical shock waves are accelerated, boosting electromagnetic emission.

In the dense region between two pre-merging clusters, such turbulence and shock waves could be generated in the early stages of a merger. And the team’s findings suggest this could be especially true if the clusters were already gravitationally disturbed in some way – for instance, if each cluster was a pair of smaller interacting clusters in its own right.

Botteon and his team bring two supporting arguments to this scenario. Firstly, a lower mass pair of merging clusters, only one of which had a radio halo, showed no evidence of a radio bridge in LOFAR observations, according to a paper last year.

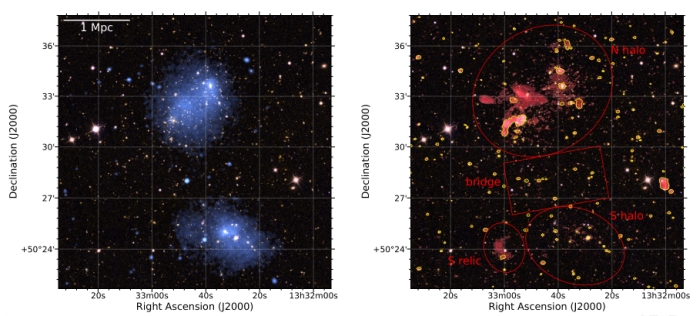

Chandra observation (left) and LOFAR (right). (Botteon et al., MNRAS, 2020)

Chandra observation (left) and LOFAR (right). (Botteon et al., MNRAS, 2020)

Secondly, the team also looked at observations of Abell 1758 taken using the Chandra X-ray Observatory. And they found that the X-ray emission very closely correlated with the radio emission at 144 megahertz – consistent with predictions of the Fermi acceleration scenario.

In the merger of Abell 0399 and Abell 0401, the researchers found that synchrotron acceleration could not alone account for the vast distances covered by the electrons. They ran simulations, and found that shock waves generated by the merger re-accelerated high-speed electrons, resulting in an emission consistent with the LOFAR observations.

So it seems likely that there are multiple types of acceleration at play – that a magnetic field can stretch millions of light-years across space between galaxy clusters, but shock waves and turbulence add that special something that completes the bridge.

“Only two giant intra-cluster radio bridges have been detected to date,” Botteon and his colleagues wrote.

“These are among the most giant structures observed in the Universe so far, and their origin is likely related to the turbulence (and shocks) generated in the intra-cluster medium during the initial stage of the merger, which boost both the radio and X-ray emission between the clusters.”

There are quite a few merging galaxy clusters that have been identified out there in the wider Universe. Searching them for more of these mysterious radio bridges could help figure out what generates these enormous structures.

The research has been published in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.