Products You May Like

Prehistoric sculptures depicting human-like faces have some scientists thinking certain expressions might well be universal across time and culture.

New research has found ancient Maya people and other Mesoamerican civilisations, such as the Olmec, were sculpting scenes of pain, elation, sadness, anger, strain and determination in ways that are still recognisable to us up to 3,500 years later.

Collecting pictures of ancient sculptures from Mexico and Central America, researchers paid 325 English-speaking participants – gathered through Amazon’s crowdsourcing marketplace – to look at isolated faces and match them up with select emotions and emotional states.

The photographs were cropped to only show the face, with no other context given. Unbeknownst to the participants, these sculptures depicted people being held captive, or tortured, preparing for combat, playing an instrument, embracing a loved one or struggling to lift a heavy object.

Another 114 online participants were asked to read about the portraits and assign them emotions and emotional states based only on a verbal description of the situations depicted by the sculptures.

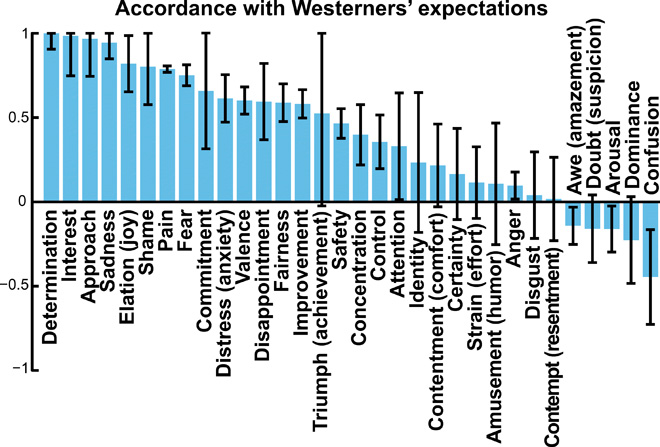

On the whole, researchers found participants interpreted the sculptures in a similar way to how the Western, English-speaking world would expect someone to feel in that scene.

This, the authors argue, suggests the faces we pull are not puppeteered by the forces of modern culture, but are inherent impulses that have existed for millennia.

“The present results thus provide support for the universality of at least five kinds of facial expression: those associated with pain, anger, determination/strain, elation, and sadness,” the authors write.

“These findings support the notion that we are biologically prepared to express certain emotional states with particular behaviours, shedding light on the nature of our responses to experiences thought to bring meaning to our lives.”

(Cowen and Keltner, Science Advances, 2020)

(Cowen and Keltner, Science Advances, 2020)

Above: Accordance between emotions perceived in sculptures’ isolated faces and Western expectations for emotions in eight portrayed contexts.

The argument joins a longstanding debate among social scientists that isn’t likely to be resolved by any one study. While some scientists think the way we portray our emotions, such as frowning or smiling, is universal and inherent to our nature, others see facial expressions as culturally dependent.

Even when looking at the same data from emotion recognition studies, these two broad schools of thought can disagree. While many studies have shown people images from other cultures to see if they identify the same expressions, others argue these methods are tainted by the presence of researchers and the influence of Western thought.

The new study gets around this somewhat, by conducting the survey online and drawing on ancient Maya art which predates any contact with Western civilisations.

Still, even this method has limitations. The authors admit they cannot know for certain whether the sculptures are accurate portrayals of everyday lives in prehistoric Mesoamerica.

“We have no direct insight into the feelings of people from the ancient Americas,” they write.

“What we can conclude is that ancient American artists shared some of present-day Westerners’ associations between facial muscle configurations and social contexts in which they might occur, associations that predate any known contact between the West and the ancient Americas.”

Still, we can’t assume that the way we interpret things today is how ancient cultures would have seen it.

Psychologist Deborah Roberson, who was not involved in the study, told Science News there are likely subtle distinctions between how the Maya expressed themselves all those years ago, and how we express ourselves today.

Such subtle variations have even been shown among us today. Comparing Western facial expressions and Eastern facial expressions, for instance, studies have shown the way we interpret happiness, surprise, fear, disgust, anger, and sadness in the faces of others may very well differ across cultures.

While this might imply facial expressions are not hard-wired or genetic, other studies have found facial expressions remain the same even for those born blind.

In all likelihood, the human arsenal of facial expressions is probably a mix of both nature and nurture. For instance, research on a culturally-isolated society in Papua New Guinea found that while some expressions, like smiling and scowling, were understood in the same way as in Western culture, an open-mouthed gasp was interpreted not as shock, but as a threat.

In a similar way, the new study found contempt, disgust and awe were particularly universal. Some facial expressions, it seems, could be more universal than others.

The study was published in Science Advances.