Products You May Like

Scientists don’t always like being right: take the team that warned in a paper published in 2017 that the St. Patrick Bay ice caps in Canada would soon disappear, for example. The latest NASA satellite imagery shows that their prediction has sadly come true, and even faster than they expected.

Scientists from the National Snow and Ice Data Centre (NSIDC) at the University of Colorado Boulder initially predicted the disappearance of the St. Patrick Bay ice caps would take place over five years, but it’s actually only taken three.

The frozen sheets, probably in place for several centuries, measured more than 10 square kilometres (3.86 square miles) combined at the end of the 1950s, and have now shrunk down to nothing. It’s a sign of the climate change that’s gaining momentum all around the world, and showing no signs of stopping.

“When I first visited those ice caps, they seemed like such a permanent fixture of the landscape,” says geographer and NSIDC director Mark Serreze. “To watch them die in less than 40 years just blows me away.”

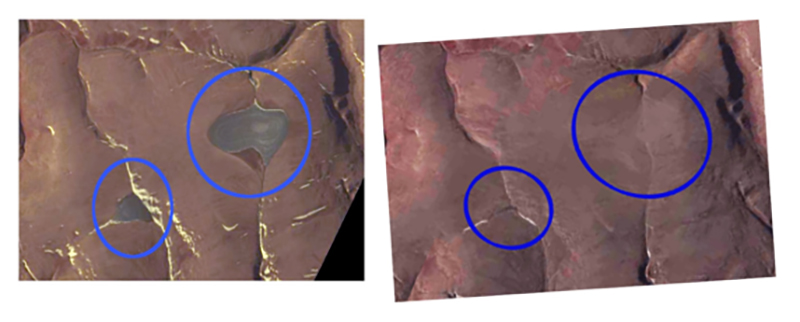

Ice cover in 2015 (left) and 2020 (right). (Bruce Raup/NSIDC)

Ice cover in 2015 (left) and 2020 (right). (Bruce Raup/NSIDC)

Serreze was a young graduate student when he first set foot on the ice caps in 1982, and he was the lead author of the 2017 paper alerting the world to their drastic demise. By 2015, the ice caps were only five percent the size of what they were in 1959.

Recent imagery from the Advanced Spaceborne Thermal Emission and Reflection Radiometer (ASTER) instrument on the NASA Terra satellite shows no trace of the St. Patrick Bay ice at all. The ice in this region is unlikely to return any time soon.

The two ice caps that have vanished are part of a group on the Hazen Plateau, in the north of Ellesmere Island in Nunavut, way up in the Arctic Archipelago – one of the most northerly points of Canada.

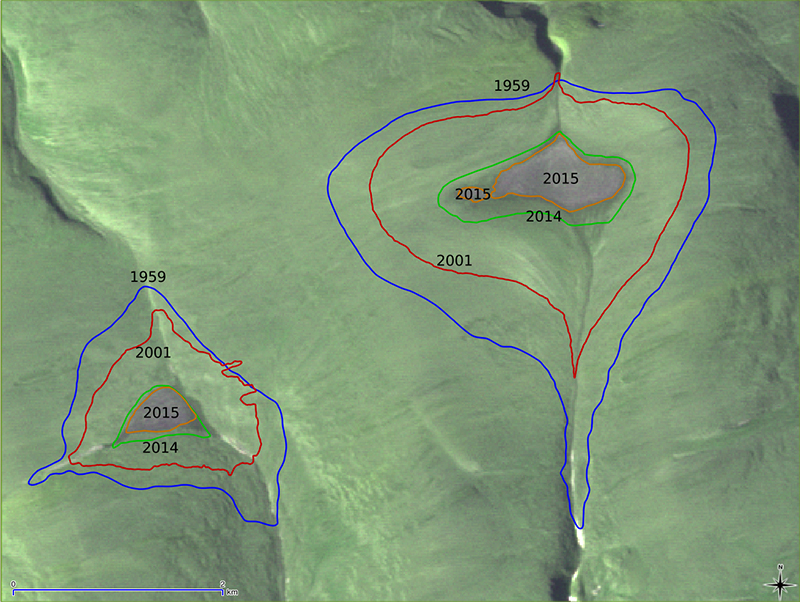

Two ice caps often linked with the St. Patrick Bay pair, the Murray and Simmons ice caps, are faring better due to their higher elevation – in 2015 their ice cover was at 39 percent and 25 percent respectively, compared with the 1959 figure. However, scientists think they too could soon be gone.

When Serreze and his colleagues first started surveying the Hazen Plateau ice at the start of the 1980s, scientific consensus on global warming was still forming, and some researchers had suggested the planet was actually in a period of global cooling. The studies started back then were partly an attempt to find out one way or the other.

Ice cover tracked over time. (NSIDC)

Ice cover tracked over time. (NSIDC)

Now there’s no doubt what’s happening. While the St. Patrick Bay ice caps may not be two of the most famous or significant points of geological interest in the world, they represent a small microcosm that reflects what’s happening to our planet as a whole.

They’re also a reminder that while scientists aren’t infallible, they very often do know what they’re talking about – and that when we get warnings about what’s coming our way in the future, we’d do well to take heed and to take action.

“We’ve long known that as climate change takes hold, the effects would be especially pronounced in the Arctic,” says Serreze.

“But the death of those two little caps that I once knew so well has made climate change very personal. All that’s left are some photographs and a lot of memories.”

The original 2017 research was first published in The Cryosphere.