Products You May Like

A liquid phase originally proposed in the 1910s has finally been realised. Using a liquid crystal compound, scientists have discovered a new “ferroelectric nematic” phase that could open up an entire new class of materials and technological advances.

There are many phases of liquid crystal, but one of the most common is the nematic phase. This is the phase that enables liquid crystal display technology, so you can probably understand why scientists are interested in it.

Such phases are defined by how the molecules behave within the material. The liquid crystal compound is made up of rod-like organic molecules with positively and negatively charged ends, somewhat like really tiny bar magnets.

In a nematic phase, these molecules are divided with half pointing one way, and the other half pointing the other, arranged more or less at random.

But in the 1910s, two physicists – Peter Debye and Max Born – proposed a different scenario for the molecular arrangement.

According to their two papers – published in 1912 and 1916, respectively – it should be possible to design a liquid crystal in such a way that the molecules fall into a state of polar order: This means there should be clear patches where the poles of the molecules are all oriented in the same direction, and this direction can be flipped by applying external electric fields.

Such a property is well documented in solid crystals; it’s known as ferroelectricity – so named because of its similarity to ferromagnetism. But, although the same ferroelectric behaviour had been hypothesised in nematic liquid crystal, it has remained elusive.

Then, in 2017, a team of physicists revealed they had developed a new rod-shaped organic molecule that could be useful for liquid crystal – the compound RM734. In subsequent studies, RM734 displayed some unusual behaviours.

In particular, while RM734 behaved like a conventional nematic liquid crystal phase at higher temperatures, its behaviour was more unusual when temperatures were lower – the molecular orientation was observed deforming in a “splay” arrangement.

This is where the new research comes in – physicists at the University of Colorado, Boulder were intrigued by this weird behaviour, and went in for a closer look.

They were mucking about with RM734 under a polarised light microscope, and applied a weak electric field to try to induce the splay nematic phase.

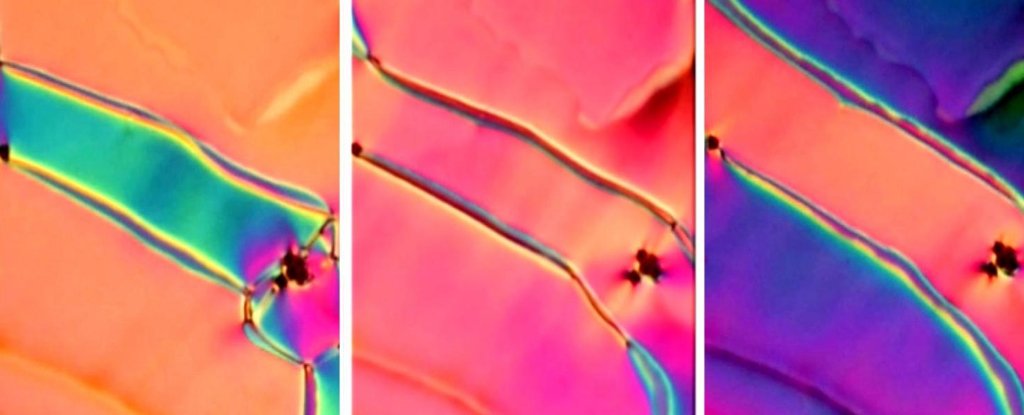

That splay arrangement did not emerge, but something else did: patches of bright colours around the edges of the cell containing the RM734 liquid crystal.

“It was like connecting a light bulb to voltage to test it but finding the socket and hookup wires glowing much more brightly instead,” said physicist Noel Clark of UC Boulder.

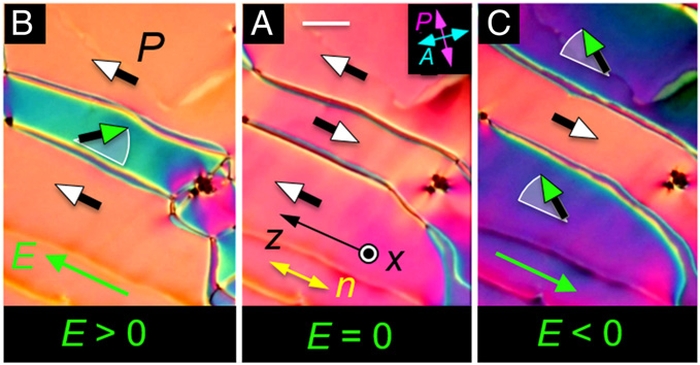

(Chen et al., PNAS, 2020)

(Chen et al., PNAS, 2020)

Further tests revealed that this phase of RM734 was between 100 and 1,000 times more responsive to external electric fields than other nematic liquid crystals, suggesting that the molecules demonstrate polar order.

And, when cooled from higher temperatures, ordered patches appeared spontaneously in the sample, with nearly all the molecules in each patch pointing in the same direction.

“That confirmed that this phase was, indeed, a ferroelectric nematic fluid,” Clark said.

They’re still not sure how or why RM734 displays this ferroelectric nematic phase, but its existence suggests that more ferroelectric fluids may be possible – ones we are yet to discover. This, in turn, could open doors to new nematic physics and new technology, including display technology and, the researchers said, computer memory.

The team is now investigating how RM734 can demonstrate ferroelectricity, hoping to reveal further details on this discovery. Who knows where this will lead?

“There are 40,000 research papers on nematics, and in almost any one of them you see interesting new possibilities if the nematic had been ferroelectric,” Clark said.

The research has been published in PNAS.