Products You May Like

Music has the power to transport us to other times and places, whether it’s the neighborhood we grew up in or a moment long lost to prehistory. Researchers have now analyzed a 55-note snippet of sheet music from 16th century Scotland, recreating a sound associated with a culture for which no other music has survived.

The notation was found in the margins of a page attached to a book that’s of historical importance in its own right: the Aberdeen Breviary of 1510. The collection of prayers, readings, and hymns is not on the bestseller lists now, but was the first full-length tome to be printed in Scotland.

A team from KU Leuven in Belgium and the University of Edinburgh in the UK have now analyzed the musical fragment, which had been discovered in the book back in 2011.

Though the fragment has been matched with a little-known Christian chant still sung in some Anglican churches during Lent today called Cultor Dei, memento (“Servant of God, remember”), the researchers aren’t sure if the notes were intended to guide instruments or a choir. Nonetheless, the scrap of notation is enough for experts to expand their knowledge on pre-Reformation liturgical culture in Scotland.

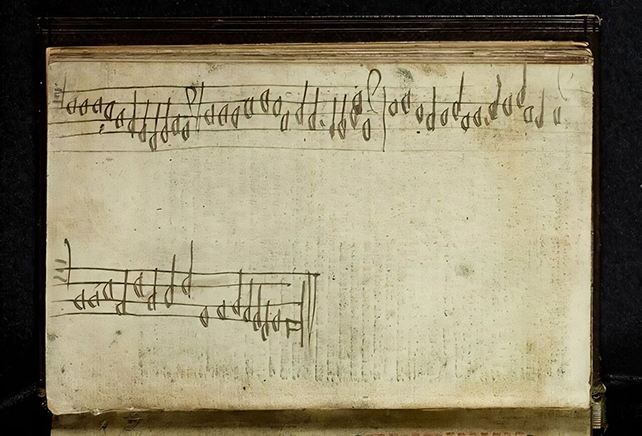

The recovered musical fragment. (National Library of Scotland/CC-BY-4.0)

The recovered musical fragment. (National Library of Scotland/CC-BY-4.0)

“From just one line of music scrawled on a blank page, we can hear a hymn that had lain silent for nearly five centuries, a small but precious artifact of Scotland’s musical and religious traditions,” says musicologist David Coney, from the University of Edinburgh.

“The fact that our tenor part is a harmony to a well-known melody means we can reconstruct the other missing parts.”

The music came without any kind of title or attribution attached to it, but the researchers recognized it as a polyphonic composition on two lines: a type of music where multiple melodies are sung or played at the same time.

That then led to Cultor Dei, memento. The notation aligns perfectly with the tenor part of a vocal harmonization of the hymn. You can hear what a sung version of the notation may have sounded like in a reconstruction posted here.

It’s one of very few musical records we have from this period of time, and the only one that’s survived from northeast Scotland, making it a crucial new finding for scholars of this period of music.

“For a long time, it was thought that pre-Reformation Scotland was a barren wasteland when it comes to sacred music,” says musicologist James Cook, from the University of Edinburgh.

“Our work demonstrates that, despite the upheavals of the Reformation which destroyed much of the more obvious evidence of it, there was a strong tradition of high-quality music-making in Scotland’s cathedrals, churches and chapels, just as anywhere else in Europe.”

The study also investigated the history of the book’s ownership and creation, finding connections to Aberdeen Cathedral and St Mary’s Chapel in Rattray in Aberdeenshire but no indication as to who might have written the music. The finding has encouraged the researchers to look at other similar texts for musical cues – quite possibly noted down in the margins.

“It may well be that further discoveries, musical or otherwise, still lie in wait in the blank pages and margins of other sixteenth-century printed books held in Scotland’s libraries and archives,” says musicologist Paul Newton-Jackson, from KU Leuven.

The research has been published in Music & Letters.