Products You May Like

Some historians have argued for years over which movie was the first slasher. Some believe that films like Alfred Hitchcock’s 1960 horror masterpiece Psycho and the Giallo sub-genre have all influenced and shaped the slasher into what it ultimately became. This year, two of those influential films are celebrating milestone birthdays: director Tobe Hooper’s The Texas Chain Saw Massacre (released in October 1974) and director Bob Clark’s Black Christmas (released in October 1974 in Canada and in December in the United States). In honor of these films’ 50th anniversaries, I’m going to take a look at the influence they had on a film that would be released four years later and is widely recognized as where all the conventions and elements of the slasher crystalized into the sub-genre we know today: John Carpenter’s 1978 film Halloween.

These films share several qualities like distinctive and creepy scores and subverting seemingly safe holidays. But my focus will be on the element that really makes a slasher stand out: its killer. So, grab your favorite sharp instrument, put on a creepy mask, and come along with me because we’re going to celebrate the birthdays of The Texas Chain Saw Massacre and Black Christmas by looking at how Leatherface and Billy helped shape (pun intended) Halloween’s The Shape, a.k.a. Michael Myers.

Black Christmas And One Creepy Killer

It’s no secret that Black Christmas influenced Halloween. In the special feature, “Black Christmas Legacy,” on Scream Factory’s 4K UHD release of Black Christmas, Bob Clark says:

“I was going to direct a film that John wrote a couple of years after Black Christmas. He was a big fan of Black Christmas, and he was just beginning his career. And John asked me if we were ever going to do a sequel to Black Christmas. I said, ‘No. This film is the last horror film I was going to do.’ He asked me if I did do a sequel what I would do. I said, ‘What I thought I would do is I would make it the following fall. Somehow in the interim, the killer had been caught and he’d been institutionalized. And I’d have him escape. Nobody knows it at first, and he’s stalking them again at the Black Christmas sorority house.’ And I was going to call it Halloween.

“Now when you think of what John Carpenter did; he wrote a script really quite different from what I did, there’s a basic core of like a sentence, cast it, directed it, edited it, and did the music.”

So, we know that John Carpenter saw Black Christmas and saw just how effective the opening POV shot of its killer, Billy, prowling around the sorority house. Halloween opens with a similar shot from the perspective of young Michael Myers going up the stairs and murdering his sister Judith, then descending the stairs and stepping outside. There are also several shots from the perspective of an adult Michael.

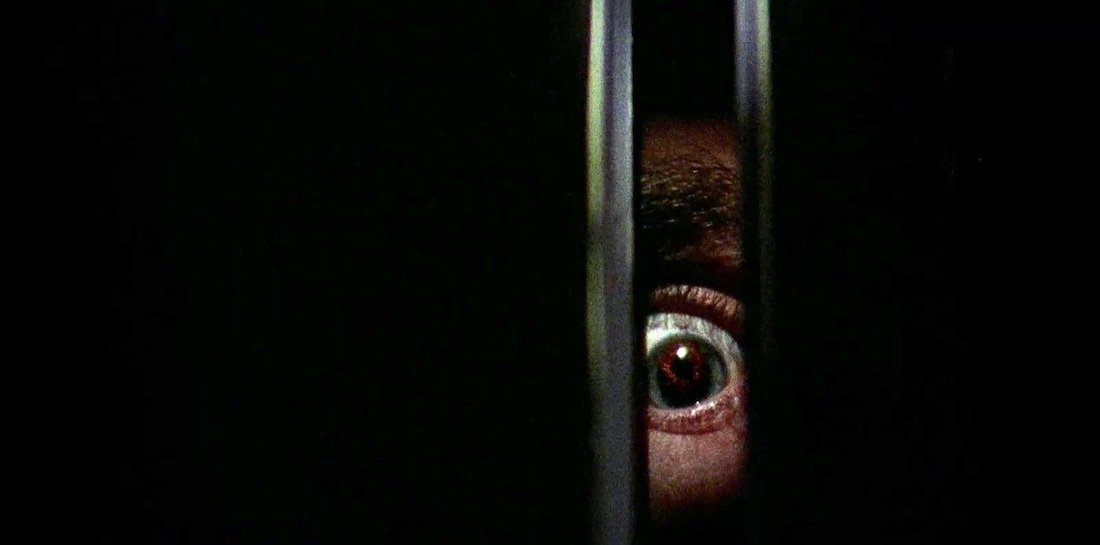

Most of Billy’s scenes in Black Christmas are filmed from his perspective. That’s a large part of why the film is so scary. We never see his full body when he descends from the attic to prowl about the house, make his phone calls, or even during his kills. The most we see of him is an eye and a shadowy figure right before he kills Margot Kidder’s Barb. It’s like he’s a formless, unknowable shape (see what I did there) preying upon the women of this sorority house.

Who Needs A Motive?

That’s what’s so terrifying about Billy—he seemingly has no motive. Sure, his absolutely chilling and obscene phone calls provide some clues to his motives. But these clues raise more questions than they answer though, and no real definitive answers are provided. Billy is a terrifying and iconic killer because he taps into one of our most primal fears: the unknown.

Later films provided Michael Myers with a motive for his killings, but the original Halloween did not. Like Billy, we’re left to wonder how did this young boy transform into a murderer. And the film never gave us an answer. We were left to anxiously ponder what Billy and Michael’s victims did to draw their murderous attention.

Both Billy and Michael also have an uncanny ability for stealth. Billy is able to secretly dwell in the sorority house attic and move about virtually undetected. The only times he’s seen is when he’s going in for the kill. Michael takes the stealth of Billy to a whole new level. He manages to drive around town in a mask without raising suspicion. He even gets extremely close to his victims— like when he observes John Michael Graham’s Bob and P.J. Soles’ Lynda having sex—without being seen. And the times when he is seen and arouses suspicion? He practically vanishes into thin air.

Dramatic Killers With Artistic Flair

Plus, these two iconic killers have a flair for the dramatic. In Black Christmas, Billy takes his first victim, Claire (Lynne Griffin), and poses her in a rocking chair in front of the attic window. Adorned with the bag that suffocated her still over her head, Billy later adds a baby doll to her arms. Later, he adds Mrs. Mac (Marian Waldman) to the gruesome tableau. He also arranges the bodies of Barb and Phil so that when Olivia Hussey’s Jess finds them they deliver maximum shock and awe.

In Halloween, Michael shows off his artistic ability in the way he poses the body of Nancy Loomis’ Annie in front of his sister’s headstone, with a simply jack-o-lantern lighting the room. That act of turning their victims into gruesome art tableaus would go on to become a hallmark of the Slasher film, partly because of Billy in Black Christmas, but also because Michael in Halloween fancied himself an artist.

So What About The Texas Chain Saw Massacre?

The influence The Texas Chain Saw Massacre had on Halloween is not as widely discussed. In an essay for Variety, film critic, Owen Gleiberman argues that Halloween is in fact a knockoff of Texas Chain Saw Massacre. While I’m not sure I agree, Gleiberman’s essay does bring up some interesting points of influence between the films and the impact of horror movies in the ‘70s. He writes:

“The ’70s was the formative age of contemporary horror, a time when horror films across the spectrum were listening to and talking to each other. To be a horror fan back then was to drink from a cornucopia of movies that seemed, in their extreme way, to capture what was going on in the world as much as any movies you could name.”

The Men Behind the Masks

The first point of comparison Gleiberman brings up between Leatherface and Michael Myers is both are masked killers. Leatherface’s signature mask and the fact that it’s made of dead skin is indeed very scary. His mask is inspired by the crimes of Ed Gein, who did in fact make masks out of human flesh.

What’s especially interesting about Leatherface’s mask, though, is the fact that he has more than one, each serving a different function. We see that in the film when Jim Siedow’s Cook comes back to the house with Marilyn Burns’ Sally Hardesty in tow. Leatherface appears wearing a new mask adorned with some makeup. He’s also cooing and acting submissive. That suggests Leatherface’s masks aren’t just there to hide his face. They also allow him to play different roles in his dysfunctional family which is both terrifying and heartbreaking.

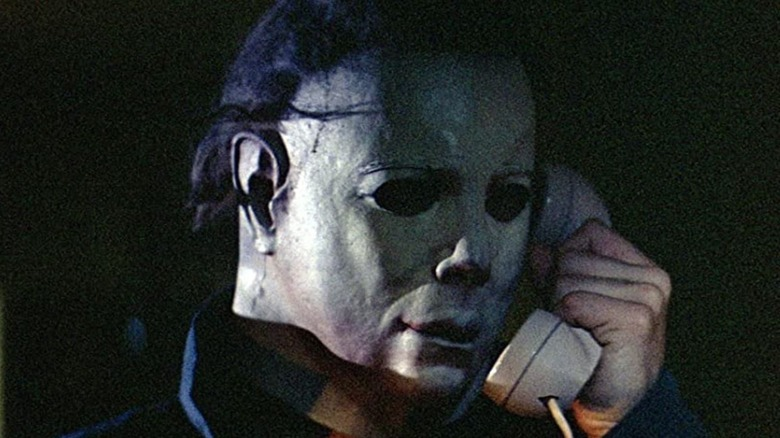

Carpenter also gives Michael Myers a mask because of the shock value, but I would argue that it also serves purpose. The mask allows Michael to become murderous. It’s vital to his identity as a killer. You see that at the beginning of Halloween when he picks up the clown mask before he murders his sister. There’s also the fact that all of Michael’s onscreen kills occur while he’s wearing that signature mask.

The real moment that shows the importance of the mask though comes in what would be Michael’s final fight with Laurie. They’re tussling, and he’s about to overpower her when she unmasks him. Instead of pressing his advantage and killing Laurie, Michael pauses to put his mask back on. That moment of hesitation shows just how important Michael’s mask is to him, and it ultimately proves his undoing. Because it allows Donald Pleasance’s Dr. Loomis time to swoop in and unload his pistol on Michael.

Hulking Monsters

Gleiberman’s other point of contention is the fact that both Michael Myers and Leatherface are hulking monsters. It’s true, but their physical power is wielded in different and truly scary ways.

Leatherface’s endurance is part of the reason why he’s so frightening. When he locks onto Sally Hardesty, he never relents. He chases her through thickets, his home, and wide fields. He only slows down to change direction or saw through obstacles in his way. The only reason he doesn’t catch her is because she makes it to the gas station where the Cook works. There, he leaves her to his family member.

In the film’s chilling climax, Leatherface is hit with a wrench, which causes him to carve a gash into his leg with his chainsaw. But still, he keeps going. Sally narrowly escapes him thanks to the assistance of a motorist who speeds her away in his truck.

Michael Myers also has seemingly superhuman endurance, but it’s his strength that’s more on display in Halloween. He does not need to run because when things are placed in his way, he just smashes through them with his fists. You get a sense of just how strong he is when he hoists Bob off the ground before sticking him to the wall with his knife.

So, Gleiberman argues that because of the masks and the hulking killers Halloween is a rip-off of The Texas Chain Saw Massacre. Sure the influence is undeniable; as is the impact of Black Christmas. But that doesn’t mean Halloween is a combined ripoff of The Texas Chain Saw Massacre and Black Christmas. No, what made Halloween a seminal classic is what their script co-writers Carpenter and Debra Hill did: they took effective elements from other works, mixed them together, and added something new to create something truly original. The brand new element they added was an unsympathetic killer.

The Key To A Good Slasher Villain: No Empathy

Leatherface is given plenty of horrific moments in The Texas Chain Saw Massacre, but he’s also given a few scenes of pathos. The first comes after he strikes down Allen Danziger’s Jerry. He screams in distress and goes to check the window. He then sits down, drops his hammer, and puts his head in his hands. This suggests he was actually quite scared of all these strange people suddenly appearing in his home. The other moment comes when the Cook arrives home and beats and yells at him. You get the sense that he’s frequently tormented by the Cook.

Billy, at first, seems less sympathetic than Leatherface. But when you consider the original title of Black Christmas was Stop Me, his actions are cast in a whole new light. Yes, Billy’s phone calls are terrifying, but what if they’re actually a cry for help? On many of the calls, he seems to be recounting some nightmarish past event. Is he violently acting out until somebody stops him? The film doesn’t offer a definitive answer, but it is something to think about.

Unlike Billy and Leatherface, Michael never makes any sounds of distress. He doesn’t vocally communicate in the film at all. We only hear the sound of his breathing. We do see his actions though and hear him described by the person who knows him best: Dr. Sam Loomis. Loomis of course talks about Michael being a creature of pure evil even from a young age. His commitment to raising the alarm about Michael’s escape and the Shape’s subsequent rampage shows Loomis was justified in his beliefs.

The moment that really sells the fact that Michael is a vicious and unrepentant killer is his murder of Bob and the iconic head tilt that comes after. Michael doesn’t say a word—just that head tilt speaks volumes. It’s the body language of someone delightfully surprised by what they just did.

So, ultimately the reason why Black Christmas and The Texas Chain Saw Massacre have such enduring legacies is twofold. One, they’re both genuinely scary movies dealing with timeless fears. The second is great horror stories don’t just scare people. They inspire future generations to take the effective elements of past tales, remix them, and add something original to the mix to create new masterpieces of fear like Halloween.

Categorized:Editorials