Products You May Like

The first ice-free day in the Arctic Ocean could arrive as soon as this decade, warns a new study.

Climatologists from Colorado University (CU) Boulder and the University of Gothenburg have used computer models to investigate when the Arctic might experience its first ice-free day. In this context, ‘ice-free’ means a sea ice area of 1 million square kilometers (386,000 square miles) or less.

The team used 11 different climate models to run 366 simulations of climate change from 2023 to 2100. They found that the first ice-free day in the Arctic appeared across quite a wide range of possibilities: it could occur in as little as three years, or it might not happen by the end of the century.

However, the majority of simulations predicted that this fateful day would arrive within 7 to 20 years. That was the case even if humans reduced their greenhouse gas emissions – which we’re doing a terrible job of so far.

Nine of the simulations reached an ice-free day within three to six years. This scenario is unlikely but poses a high risk, so the researchers investigated the conditions that led to such a quick transition.

All it would take is an unusually warm fall, winter, and spring, which primes the following summer to melt more sea ice. If this pattern holds for three consecutive years, the first ice-free day would occur by September of a given year.

An ice-free day wouldn’t be a one-off event either. More would of course follow, eventually culminating in entire months below the ice-free threshold.

“The first ice-free day in the Arctic won’t change things dramatically,” says Alexandra Jahn, CU Boulder climatologist.

“But it will show that we’ve fundamentally altered one of the defining characteristics of the natural environment in the Arctic Ocean, which is that it is covered by sea ice and snow year-round, through greenhouse gas emissions.”

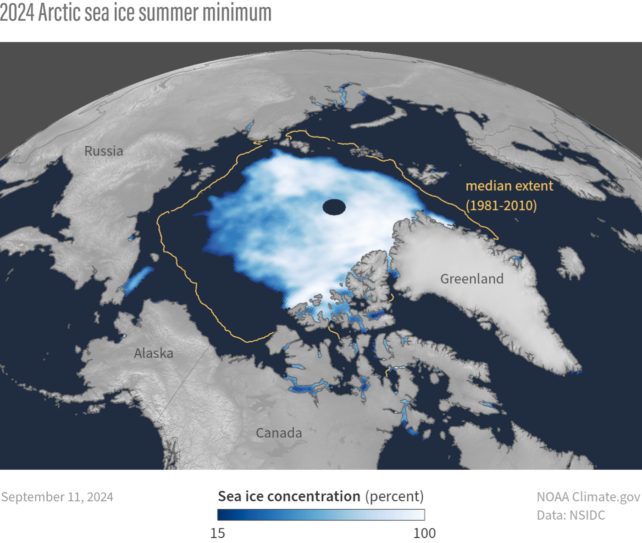

The amount of sea ice in the Arctic and Antarctic naturally shrinks and grows throughout the course of the year. The maximum and minimum extents have been monitored since November 1978 to track the effects of climate change.

This year, for example, the minimum sea ice area was recorded on September 11, at 4.28 million square kilometers. That makes it the seventh smallest area on record, with the loss showing a downward trend of 12.4 percent per decade.

Projecting forwards, scientists have previously estimated when the Arctic might become ice-free for large chunks of its summertime. For the new study, the researchers investigated an overlooked stepping stone on that path: when the first ice-free day might occur.

In all nine of the worst-case scenario simulations, sea ice was preconditioned for a few years before the first ice-free day occurred. In those years, atmospheric cooling arrives later in autumn, and warm spells appear as late as December.

During the ‘final’ winter before, temperatures linger above -20 °C (-4 °F) for extended periods, reducing the amount of new ice formed.

Spring may arrive up to one month earlier than usual, or see fewer cold spells. Heatwaves of over 0 °C become common. And finally, the summer featuring that fateful day is very warm, with temperatures over 10 °C. Storms at this time can further stress sea ice.

Together, these conditions can trigger the first ice-free day to arrive in August or September. After that first day, the Arctic remains ice-free for between 11 and 53 days in those nine quick transition simulations.

The researchers aren’t investigating this just to bum people out. The study found that ice-free days in all quick transition cases occurred in years where global warming exceeded 1.5 °C above the pre-industrial baseline – the target of the Paris Agreement.

If countries can stick to the guidelines set out in that agreement, an ice-free Arctic could be delayed, the team says. Unfortunately, 2024 is on track to be the first year above 1.5 °C of warming, so we might be heading down a negative path sooner rather than later.

The research was published in the journal Nature Communications.