Products You May Like

Bottlenose dolphins in Sarasota Bay in Florida and Barataria Bay in Louisiana are exhaling microplastic fibers, according to our new research published in the journal PLOS One.

Tiny plastic pieces have spread all over the planet – on land, in the air, and even in clouds.

An estimated 170 trillion bits of microplastic are estimated to be in the oceans alone. Across the globe, research has found people and wildlife are exposed to microplastics mainly through eating and drinking, but also through breathing.

Our study found the microplastic particles exhaled by bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops truncatus) are similar in chemical composition to those identified in human lungs. Whether dolphins are exposed to more of these pollutants than people are is not yet known.

Why it matters

In humans, inhaled microplastics can cause lung inflammation, which can lead to problems including tissue damage, excess mucus, pneumonia, bronchitis, scarring and possibly cancer. Since dolphins and humans inhale similar plastic particles, dolphins may be at risk for the same lung problems.

Research also shows plastics contain chemicals that, in humans, can affect reproduction, cardiovascular health and neurological function. Since dolphins are mammals, microplastics may well pose these health risks for them, too.

As top predators with decades-long life spans, bottlenose dolphins help scientists understand the impacts of pollutants on marine ecosystems – and the related health risks for people living near coasts. This research is important because more than 41% of the world’s human population lives within 62 miles (100 km) of a coast.

What still isn’t known

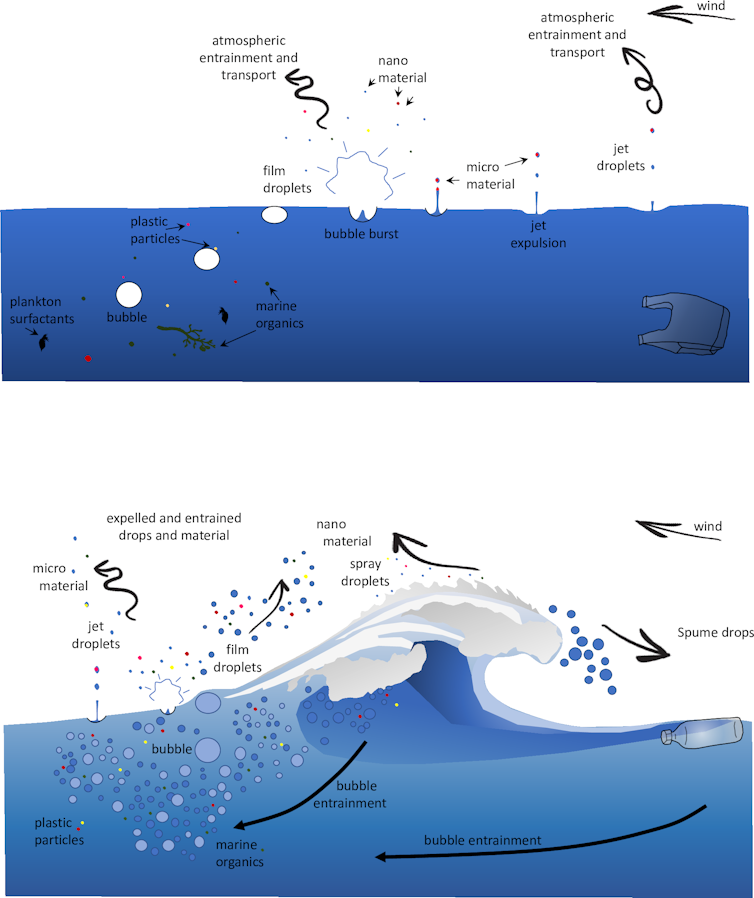

Scientists estimate the oceans contain many trillions of plastic particles, which get there through runoff, wastewater or settling from the air. Ocean waves can release these particles into the air.

In fact, bubble bursts caused by wave energy can release 100,000 metric tons of microplastics into the atmosphere each year. Since dolphins and other marine mammals breathe at the water’s surface, they may be especially vulnerable to exposure.

Where there are more people, there is usually more plastic. But for the tiny plastic particles floating in the air, this connection isn’t always true. Airborne microplastics are not limited to heavily populated areas; they pollute undeveloped regions, too.

Our research found microplastics in the breath of dolphins living in both urban and rural estuaries, but we don’t yet know whether there are major differences in amounts or types of plastic particles between the two habitats.

How we do our work

Breath samples for our study were collected from wild bottlenose dolphins during catch-and-release health assessments conducted in partnership with the Brookfield Zoo Chicago, Sarasota Dolphin Research Program, National Marine Mammal Foundation and Fundación Oceanogràfic.

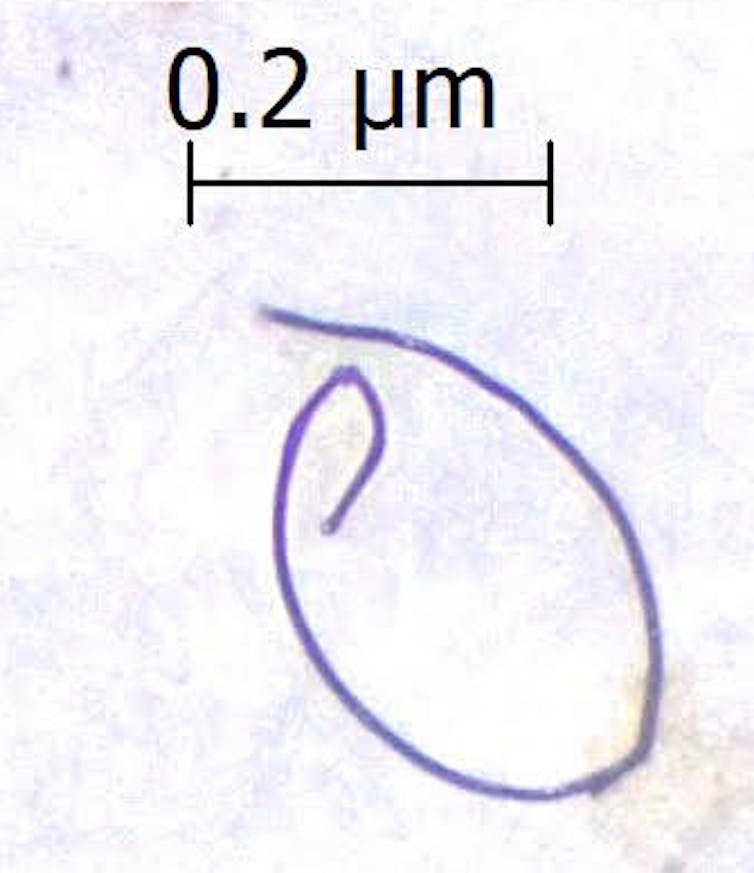

During these brief permitted health assessments, we held a petri dish or a customized spirometer – a device that measures lung function – above the dolphin’s blowhole to collect samples of the animals’ exhaled breath. Using a microscope in our colleague’s lab, we checked for tiny particles that looked like plastic, such as pieces with smooth surfaces, bright colors or a fibrous shape.

Since plastic melts when heated, we used a soldering needle to test whether these suspected pieces were plastic. To confirm they were indeed plastic, our colleague used a specialized method called Raman spectroscopy, which uses a laser to create a structural fingerprint that can be matched to a specific chemical.

Our study highlights how extensive plastic pollution is – and how other living things, including dolphins, are exposed.

While the impacts of plastic inhalation on dolphins’ lungs are not yet known, people can help address the microplastic pollution problem by reducing plastic use and working to prevent more plastic from polluting the oceans.![]()

Leslie Hart, Associate Professor of Public Health, College of Charleston and Miranda Dziobak, Instructor in Public Health, College of Charleston

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.