Products You May Like

No one yet knows what threat plastic pollution poses to human health, but the recent realization that we are drinking invisible fragments of plastic along with our water is making many understandably uneasy.

To stop microplastics and nanoplastics from penetrating deep into our bodies and brains, researchers at the University of Missouri have come up with a potentially sustainable and safe way to rid water of microscopic pollutants.

Using natural liquid ingredients that have low toxicity, the team has shown they can remove around 98 percent of nanoscopic polystyrene beads from fresh and salt water.

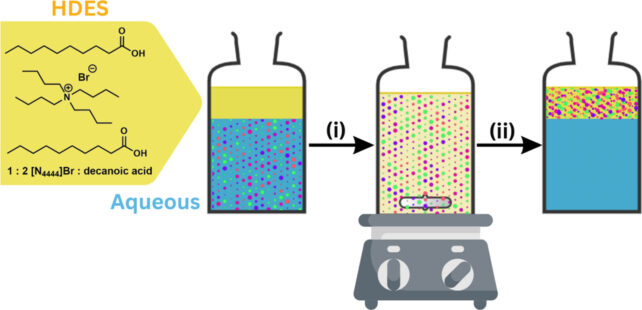

The solvent that researchers engineered floats on the surface of water, kind of like oil. A quick mix, however, and – voila! – the liquid picks up microscopic plastics in the water and carries them to the surface.

Sucking up the top layer of liquid with a pipette, researchers at the University of Missouri found they could remove nearly all nanoplastic beads from their contaminated water samples.

In salt water, the method worked at extracting 99.8 percent of all polystyrene pollutants.

The proof of concept showcases a cost-effective and potentially “sustainable solution to the nanoplastics problem”, argue researchers from Mizzou. With further research, the technique could even prove useful for cleaning water of other pollutants, like forever chemicals.

Previous studies have found that tap water and bottled water contain numerous microscopic bits of plastic, especially nanoplastics that are under a micrometer in size. In fact, by some estimates roughly 240,000 nanoplastic particles exist in each liter of bottled water, on average.

These non-biodegradable entities are sometimes made purposefully and sometimes formed from broken-down microplastics.

They can easily seep into natural ecosystems, through rivers or drainage networks, or from the abrasion of tires, agricultural runoff, or wastewater treatment plans.

Today, nanoplastics are found in bodies of water the world over, including places as remote as the deep sea, the Arctic, and mountain lakes.

“Nanoplastics can disrupt aquatic ecosystems and enter the food chain, posing risks to both wildlife and humans,” says chemist Piyuni Ishtaweera, who conducted the research while at Mizzou.

In addition, harmful chemicals, like heavy metals or flame retardants, can also cling to the surface of nanoplastics, where they can possibly interact with biological membranes.

Removing such tiny pollutants from the environment is no easy feat.

Just recently, researchers in China found that boiling tap water can remove up to 90 percent of nano- and microplastics.

This could be a simple way to remove pollutants from drinking water, but it isn’t useful for larger bodies of water that might be contaminated.

The new technique from Mizzou could tackle nanoplastic pollution in a far more scalable way.

“Our strategy uses a small amount of designer solvent to absorb plastic particles from a large volume of water,” explains chemist Gary Baker.

“Currently, the capacity of these solvents is not well understood. In future work, we aim to determine the maximum capacity of the solvent. Additionally, we will explore methods to recycle the solvents, enabling their reuse multiple times if necessary.”

The study was published in ACS Applied Engineering Materials.