Products You May Like

How much have you changed over the past couple of years? The passage of time continues, constantly, unremittingly. We’re all getting older, and time’s arrow marches on. It’s… inevitable. Recently, I had the opportunity to sit down with Citizen Sleeper 2: Starward Vector’s lead dev Gareth Damian Martin, after playing some of the upcoming sequel. In case you couldn’t tell, and thought I was just being introspective, in Citizen Sleeper 2, the passage of time is important.

Take Bliss, for example. Bliss is a character you can meet in the first Citizen Sleeper, and they’re back in the sequel. Those of you that met them in the first game might remember that, at that point in time, they used she/her pronouns. But now, an indeterminate amount of time later, they’ve realised they are non-binary.

In Citizen Sleeper 2, when you meet Bliss, they offer to help you out. Fans enjoyed their presence, but this resurfacing is about more than simply jingling keys for players of the first game. For Martin, Bliss presented “an opportunity to have this kind-of moment of solidarity, and a fun discussion between a non-binary person and a Sleeper about their experiences; something that I’m trying to bring to the Forefront.”

When you make any game (particularly one where you’re serving as the sole writer), it can be difficult to gauge how people might respond to it. After the runaway success of the first game, for Martin, Citizen Sleeper 2 was about making narratives about gender identity and other marginalized characteristics more concrete, and more than just metaphors.

“In Citizen Sleeper, it’s a big part of the game because it’s where I wrote from, but putting it out in the world and having people react to it allows me to then look at everything in a more intentional way and go, ‘okay, I need to make sure that’s still part of the game’.

“One of the readings of Citizen Sleeper that I didn’t love to see was where people were behaving like it was one of those science fiction stories; where you do something like you replace a whole group of minoritized people with a metaphor. I really didn’t want that to be Citizen Sleeper, and so I’m like, ‘okay, no, but there are trans and non-binary people in the Citizen Sleeper universe.'”

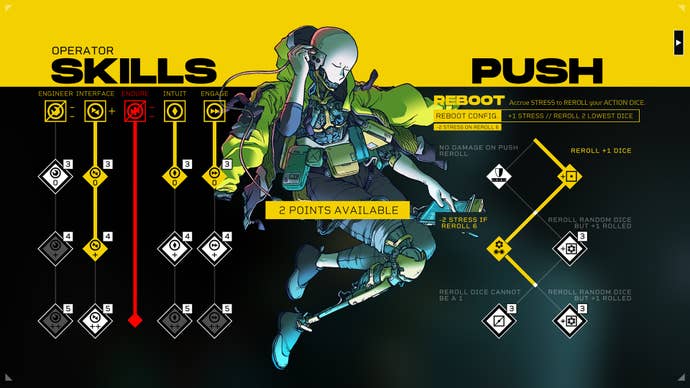

With these explicit changes to the world-building came changes to in-world come mechanics, too. I wrote about this in my preview of the game, but Starward Vector works quite differently from its predecessor. Different classes have different strengths and weaknesses, some having skills they can’t use at all. The game’s main mechanic is literally rolling dice – of which you have six you can use every cycle – but if you attempt something that you aren’t skilled in, you’ll more likely get a negative result.

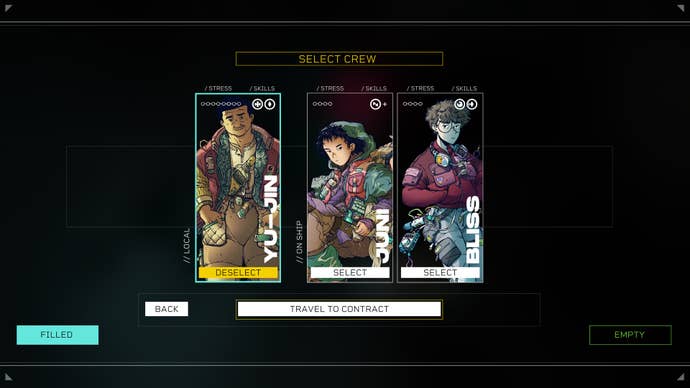

Alongside that, though, you now have to assemble a crew for different jobs you take on, with different characters having their own strengths that can make up for what you lack. But as a result of this balancing act, various NPCs can end up living to serve you, with no autonomy of their own. To combat this, Martin has attempted to give various characters their own sense of agency.

“[Citizen Sleeper is] not about, ‘oh yeah, you’re the captain. This is your crew.’ When you arrive at a location, they often go off and do their own thing because you don’t control them. That’s especially funny when you arrive at places and Serafin’s like ‘I’ve got something I need to do and the thing is you can’t fly the ship’. So you just have to deal with the fact that Serafin’s off doing something. A big core part of Citizen Sleeper 1 was the feeling that the characters have a lot of agency, and they’re not just tools for you to move around.”

This isn’t Dragon’s Dogma, where you can decide how your pawns look and work, no: in Starward Vector, each crew member you take on a job has their own dice you can roll, but if you try to make them do something they’re not good at (or don’t want to do) you can expect to hear their feedback. Little things like this really help bring the characters to life, as if they really have their own wants and needs, something that can be quite difficult to do in a game without motion capture, or actors to deliver their lines.

Martin explains that they put a lot of thought into the ways someone might react to certain situations, citing a character you meet early on in the game, Yujin, who ends up potentially causing a bit of trouble for you on your first job. “You have these fun moments where it’s like ‘oh yeah I get to pay that off’ and it gets to have a progression because these people are around you a lot more… My writing process is very much like that of a [TTRPG Dungeon Master]. I write a bit, but leave myself a lot of loose ends.”

Citizen Sleeper isn’t just about its characters, though. There’s also the world they live in. The first game was set entirely on one space station, The Eye, with Martin noting how they love stories about “one time and one city” but Starward Vector’s setting is very different. Primarily because it doesn’t have just one space station to visit, but many. One of the the most lauded things about the first game was the way in which the world was built up, with small bits of flavour text allowing you to build a vivid image of what The Eye looks like.

Starward Vector, in turn, takes the micro and makes it macro – filling the world with details that make these star systems living, breathing places. Martin spoke to me of their time designing the ecosystem of their first game, In Other Waters, and the way they had to think about things like whether there’s sunlight in a certain area, and what that might mean for the biology of certain creatures there. This line of thinking carries through to Starward Vector.

“We’re in an asteroid belt at the edge of a solar system. Where do people get water? Well, okay, let’s say that there’s like an ice asteroid that’s being mined… Okay, they’ve got that. Then you map it and you’re like ‘okay, well these places get water from here, but we need somewhere to get food’ and then you’re like ‘what leftover pieces of corporate tech might have been around’.”

You can really feel the passion for this world coming through from Martin, sat in the same room with them, watching them envision this complete world that they’ve created. All of these things matter, after all, as while all these systems might be something mundane within the world of Citizen Sleeper, they’re also necessary, and inform why these characters’ lives are the way that they are. There is a war going on in the background of Starward Vector, too – one that I wasn’t able to feel the full impact of in my time with the game, but one I’m curious to see explored further.

That aspect of the game is something that’s quite real for Martin, too. Their partner is Romanian, from a country that borders Ukraine, and is still being impacted by Russia’s on-going invasion that started in 2022 (the year the first Citizen Sleeper released, incidentally).

“I’ve spent a lot of time going to Romania and seeing how the war in Ukraine has affected Romania,” they explain. “Romania is on the Black Sea, so mines wash up on the beaches in the Black Sea and it’s this interesting relationship to a war, because it’s sometimes applying a lot of pressure and, other times, it’s like it’s almost not happening. It’s different for different people. There’s this really interesting texture that I found fascinating and really relates to the theme of crisis, and that’s really important to the game. It’s a big influence on how I think about the belt in CS2 as being on the ‘shore of war’.”

Mortality, and your relationship to your body, and how it exists in physical space – these are all themes that are integral to the DNA of the first game. And they’re present again in Starward Vector, too, at once again at the forefront of Martin’s mind since they’ve endured two surgeries in the past year.

For Martin, giving your body over to someone else to look after feels like “an unusual thing” that “you do because they are objective, and they have this objective position of looking at your body as an object that you can never do.” It was this thought process that led Martin to think a lot about “health anxiety and how our bodies can be terrifying, we can have moments and psychological effects on our bodies. I experience depression as a very physical thing, and I get lots of random pains, and I know they don’t exist.”

But it feels like a lot of these ideas could have been explored in DLC, or via expansions, or add-ons. Why do the whole way and make a full sequel? I asked Maritn.

“In a way, releasing [Citizen Sleeper] into the world and seeing people reflect on it, I was like, ‘oh, there’s all of these facets to Sleepers that are really cool and interesting, and I’d love to explore these more’. Citizen Sleeper was an experiment, and I [wanted to] keep it small and tight. ‘Let’s not go crazy’. I made it in two years, put it on the world to see if it works, and it did.”

Citizen Sleeper ended up receiving three pieces of DLC, which let Martin explore particular stories that felt important for them to tell, but there was still more ion the proverbial tank.

“I’ve still got so much stuff I want to do, but I can’t tell any more of these stories because I need more systems. I want to try and push things and pull things… [and] fully work through lots of feelings about being more conscious of what Sleepers represent, and then trying to actually engage with that a bit more.”

On top of that, there’s the simple fact that no one was making this exact kind of game – where you build a crew and go on adventures – in quite the exact way that Martin wanted, so for them it was also about making the game they wished they could play.

“I’m gonna take all of the things I think about this genre, and I’m going to do my vision of it and at least I know I will have marked that off. In the same way that when I made In Other Waters; that was me making a Metroid game, even though that game doesn’t really resemble a Metroid game… so this is my response to Mass Effect 2. It may not be the same as Mass Effect 2, but that’s the whole point. The whole point is it kind of exists in all of the gaps that Mass Effect 2 has.”

Citizen Sleeper comes from Martin’s heart. Putting the first game out there let them think about this world, and this game, more broadly. “I wanted to write about being a human,” they say. “And I made a robot to do that, because we’re often not allowed, or permitted, to write about bodies in a certain way, because bodies are not supposed to be in question in fiction. Especially not in games.”

Part of what resonated with me when I played the first game were these meditations on how bodies exist, how they navigate certain spaces, how they endure life events, how they age, how they grow, how they decay. While Starward Vector puts me in the shoes of a new Sleeper, their body is still something they have to figure out, too, and based on my conversation with Martin, I’m quite confident I’m going to come away from it with plenty of fresh ideas about how I exist in the space I occupy, too.

And that’s the point of art, right?