Products You May Like

A grisly find of two skeletons maimed in exactly the same way suggests that limb amputation was used as a punitive form of punishment with shocking precision in the Eastern Zhou Dynasty of China, more than 2,000 years ago.

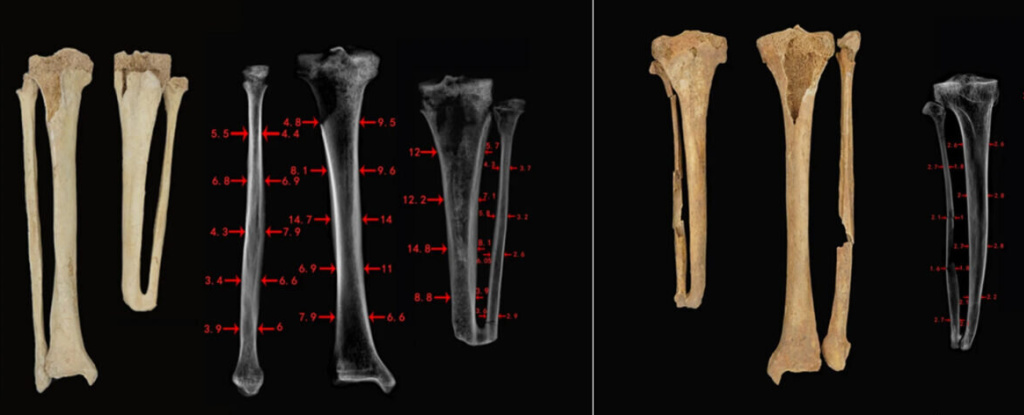

One skeleton, most likely male, that paleoanthropologist Qian Wang of Texas A&M University and colleagues studied was missing its left foot and about one-fifth of its lower left leg, which measured 8 centimeters (3 inches) shorter than the right leg.

The right leg of the second skeleton, another suspected male, also had the same length of bone chopped off – although not roughly. The men’s amputated limbs are missing similar lengths, cut within a centimeter’s difference of each other.

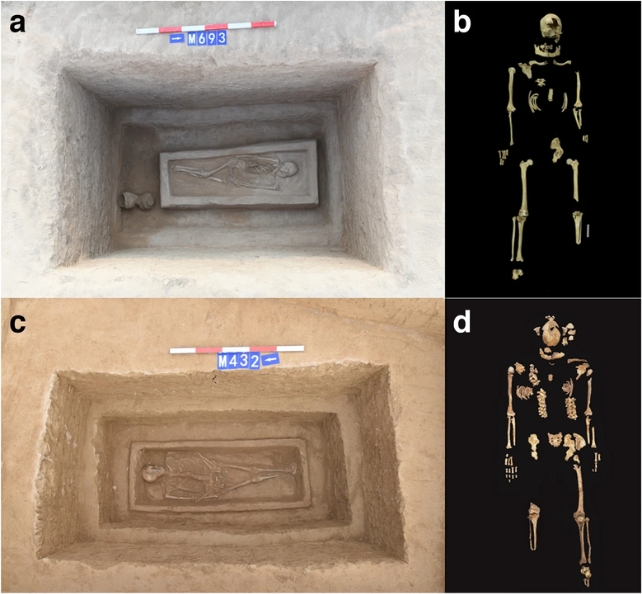

Excavated from a site close to Sanmenxia, a city in Henan Province, China, the skeletons date to between 2,300 and 2,500 years old, placing them in the Eastern Zhou Dynasty, whose leaders ruled parts of China from 771 to 256 BCE.

“This discovery, along with some previous findings, corroborates with historic written records of law and punishment” used during the Eastern Zhou Dynasty, Wang and colleagues write in their paper, which was published in March.

From the bones alone it’s impossible to know what these two men were accused of. Based on historical documents, however, Wang suggests one man might have received a harsher punishment than the other because right leg amputations were reserved for more serious offenses.

“Punitive amputation of both feet was reserved for even higher serious felonies,” Wang says.

Wang and colleagues suggest the skeletal remains are evidence of skillful amputation that, despite being used for punishment, also involved nursing to facilitate the men’s recovery. The two amputees likely survived for years afterwards as their leg bones showed significant signs of healing; the bone cleanly fusing where it had been cut off.

“Since amputation by penalty was not an uncommon phenomenon, they might [have] returned to normal social life and were buried in a proper manner after death,” Wang says.

According to the researchers’ analysis, the men likely held a high enough social status to permit their rehabilitation.

Each skeleton was found in a two-layered coffin buried in a north-south direction; an orientation that was typically reserved for members of the upper class. Commoners, on the other hand, were relegated to smaller, east-west oriented tombs.

Grave goods, along with isotopes in the bones indicating the men ate a protein-rich diet, also suggest they were aristocrats, possibly low-level officials.

History is littered with other examples of amputation in ancient cultures, the earliest documented case being that of a child who lived 31,000 years ago in Indonesian Borneo, and had their left foot surgically removed several years before they died.

Other ancient amputees have also had limbs removed for medical reasons: in 18th or 19th century Spain for an infected wound, or to treat diseases such as diabetes in ancient Egypt.

But limbs have been lopped off from Peru to Portugal for rituals and to punish offenders, the archaeological record shows.

As for the two Chinese men who paid for their unknown crimes with their limbs, Wang says: “These cases enrich our understanding of the penal laws and their implementations, medical care capabilities, and the general benevolent attitudes towards those who were punished by law from the social and archaeological contexts of ancient China.”

The study has been published in Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences.