Products You May Like

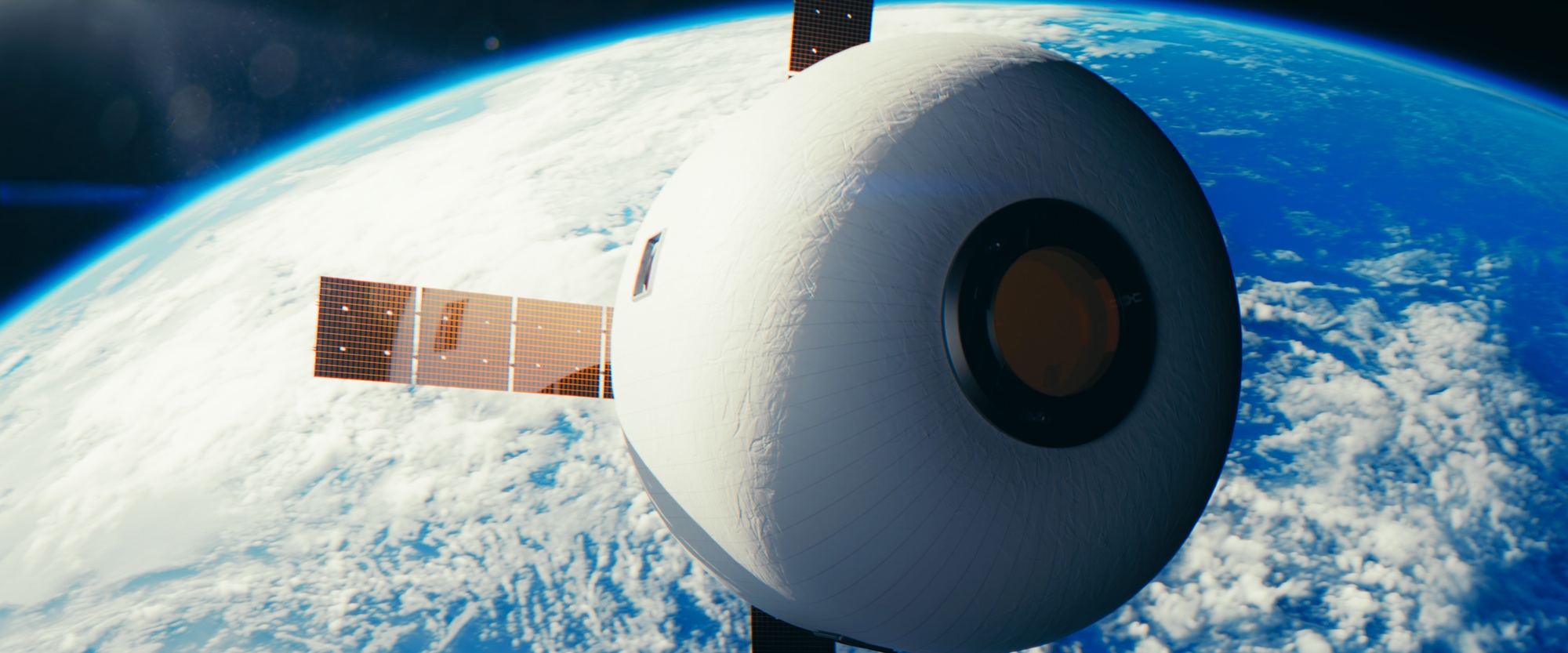

COLORADO SPRINGS — A startup has unveiled plans to develop inflatable modules that the company believes can be made larger and less expensive than alternatives, supporting commercial space stations and other applications.

Max Space is developing a series of expandable modules, the first of which is scheduled to launch on a SpaceX rideshare mission in 2025. That Max Space 20 module, compacted into a volume of two cubic meters for launch, will expand to 20 cubic meters after deployment, making it the largest expandable module flown to date.

Aaron Kemmer, co-founder and chief executive of Max Space, said in an interview that his interest in expandable modules stemmed from his experience at space manufacturing company Made In Space, which produced 3-D printers used on the International Space Station.

“What we always ran into when trying to do something meaningful was a volume bottleneck,” he said, citing an example of cramming a system to produce high-quality optical fiber that, on Earth, would span three stories into a standard ISS locker. “The hardest part wasn’t getting it to work in space. The hardest part was actually getting it to work in a limited volume.”

The concept of expandable modules is not new. The technology was central to the plans of the former Bigelow Aerospace, which launched the Genesis 1 and 2 spacecraft and built the Bigelow Expandable Activity Module (BEAM) currently on the ISS. More recently, companies such as Lockheed Martin and Sierra Space have tested on the ground, but not yet flown, inflatable modules.

Max Space is taking a different technical approach to earlier systems that used a bi-directional “basket weave” fabric structure. “When you start making fibers go in two different directions, 90 degrees apart, the result is you don’t know how much load is going in one direction or the other,” said Maxim de Jong, co-founder and chief technology officer of Max Space, whose past work included development of Genesis 1 and 2.

That requires additional material to ensure sufficient margins of safety and also makes it difficult to scale up designs to larger volumes. “Every scale-up is a point design and has to be revalidated,” he said.

Max Space is pursuing a technology called an ultra-high-performance vessel created by de Jong that distributes loads in one direction, a design that he credited to a “totally accidental discovery” while working on other concepts. That reduces the uncertainty in safety margins, which has been demonstrated in tests where modules burst at pressures within 10% of predicted levels. “The predictability is great and the scalability is great,” he said.

The company has built a version of the Max Space 20 module for testing, recently exhibiting it at the invitation-only MARS Conference hosted by Amazon founder Jeff Bezos. The company is now working on a flight version with enhancements like debris shielding.

The scalability this design offers will allow Max Space to quickly move to larger modules with volumes of 100 to 1,000 cubic meters — the latter the approximate volume of the entire ISS — later this decade. “Our big, exciting goal is…to launch the space station’s equivalent of volume in one Falcon launch,” Kemmer said, with such a module costing as little as $200 million.

An obvious application of such modules would be for future commercial space stations. “Building space station modules is hard and expensive, and a limiter to a lot of the interesting space applications like in-space manufacturing, biosciences and pharma,” he said. “What we want to do is demonstrate you can do it cheaply.”

The company’s first modules, though, could be used for other applications. Kemmer said the initial customers for the modules likely will be government agencies interested in using the modules as in-space propellant depots or other storage. “It’s definitely not our approach to rush in and put humans up in the first one.”

Max Space has no plans to build its own station, but instead be a supplier to other companies developing commercial space stations, such as through NASA’s Commercial Low Earth Orbit development, or CLD, program. “We look at our path to success as working with most other CLD companies and module providers,” he said.

That focus on developing the module technology extends to contracting out elements like the bus that provides power and propulsion as well as life support systems. “We’re focused on our core tech and building that out,” he said.

The company has raised what Kemmer described as a “sub-$10 million” seed round that is funding development of the initial Max Space 20 module and its rideshare launch. The company has less than a dozen employees and doesn’t expect to grow significantly until after the launch of that first module. “Part of our approach is to demonstrate it cheaply and with a small team on purpose,” he said.

Doing so, the Max Space founders argue, will allow them to scale up both the company and the modules incrementally. “We have a really good shot of making this happen,” de Jong said, “taking it one step at a time.”