Products You May Like

Paleontologists have unearthed the fossils of two 160 million-year-old lamprey species, discovering the once small fish had already evolved into monster chompers – growing more than ten times longer than the earliest lampreys.

The earliest fossil evidence of lampreys dates back 360 million years, earning them the nickname ‘living fossils’ due to their long history with little evolutionary change.

Today they can grow up to a meter in length, though earliest lampreys during the Paleozoic were barely a few centimeters long. The largest of the newly discovered species, Yanliaomyzon occisor, was just over 64 centimeters (25 inches) from tip to tail.

The surprisingly ginormous ancient species were discovered in the terrestrial Yanliao Biota in North China. We can learn more about the evolutionary history of lampreys and where they originated thanks to these exceptionally well-preserved Lagerstätte fossils.

“Bridging the recorded fossil and extant lampreys, these fossils offer an opportunity to reconstruct the evolutionary process and the ancestral state of modern lampreys’ feeding biology,” writes a team of researchers led by Feixiang Wu of the Chinese Academy of Sciences.

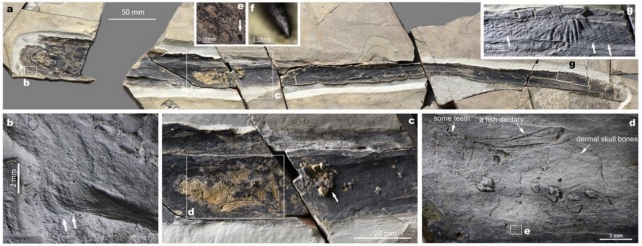

Wu and fellow paleontologists, Chi Zhang of the Chinese Academy of Sciences and Philippe Janvier of the National Museum of Natural History in France, conducted a comprehensive analysis of the two species, scanning with X-ray micro-computerized tomography to visualize the fossils in 3D.

Along with hagfish, lampreys make up the living jawless vertebrate groups. These marine creatures resemble eels with their long and scaleless bodies, but actually eels are a much newer species, with updated bodily tech like jaws and bones.

Lampreys are among the earliest vertebrates, and instead of using jaws like most ‘regular’ fish, their quite terrifying circular sharp-toothed mouth sucks the blood of other fish.

“Lampreys have great weight in the study of vertebrate evolution,” Wu, Janvier and Zhang write in their published paper.

“They are characterized by their peculiar feeding behavior of eating blood or cutting off tissues from the hosts or prey to which they firmly attach via their toothed oral sucker.”

Lampreys’ evolutionary history is still hard to figure out, though, because few fossils have been found.

It’s not clear when lampreys evolved complex teeth for feeding; early lampreys in the Paleozoic had feeding structures that seem too weak for predation. And they didn’t have the first larval stage of modern lampreys’ life cycle, where their eggs hatch as blind, worm-like critters that burrow in silt.

The physiological implications of their size, along with other fossil evidence, suggest the newly discovered species had already evolved a three-stage life cycle like today’s lampreys.

By the Jurassic period, the authors say, lampreys had better ways to feed, bigger bodies, and were predators. These newfound Jurassic lampreys have the strongest ‘biting structures’ of any known fossil lampreys, a strong indication of a carnivorous lifestyle.

“Yanliaomyzon occisor, to our knowledge, the largest fossil lamprey known so far, ranks among the largest in modern species,” Wu and colleagues write.

The adult size of living lampreys is directly linked to some of their most important biological traits. The bigger species can migrate farther and spread to wider areas, lay more eggs, and handle salt water better.

Figuring out how the Jurassic lampreys lived (and ate) is easier when you know how big their bodies were.

What’s more, skeletal remnants, including teeth, jawbones, and even the skulls of unidentified bony fishes were preserved in the intestinal tracts of both fossil species.

“The bones and skeletal relics point to a flesh-eating habit for these fossil lampreys,” the team writes, “making them the oldest records of its group with feeding mode clearly specified so far.”

The researchers think that rather than for predation, the smaller, more ancient lampreys’ mouth parts might have been used to scrape algal mats off other aquatic animals. This would have helped them find a nutritional niche in a world crowded with jawless fishes like the similarly shaped conodonts.

From their Devonian origins, lampreys’ feeding structures and habits changed drastically, according to the authors, and these fossils bridge some evolutionary gaps, as well as changing what was thought about where living lampreys originated.

“Contrary to past efforts,” they write, “our study points to the Southern Hemisphere as the biogeographic source for modern lampreys.”

The study has been published in Nature Communications.