Products You May Like

Oxford today is known as a place of learning and elite scholarship. Several hundred years ago, the university town had something of a darker reputation.

A deep dive into historical documents reveals that during the late medieval period in the 14th century CE, Oxford had a per capita murder rate four to five times higher than other high-population hubs like York and London.

And the reason? Bloody students.

Like, quite literally. Newly translated documents list 75 percent of the perpetrators of murders with known background as “clericus”, a term most commonly used to describe students or members of the then-recently founded University of Oxford. And 72 percent of the victims were also classed as clericus.

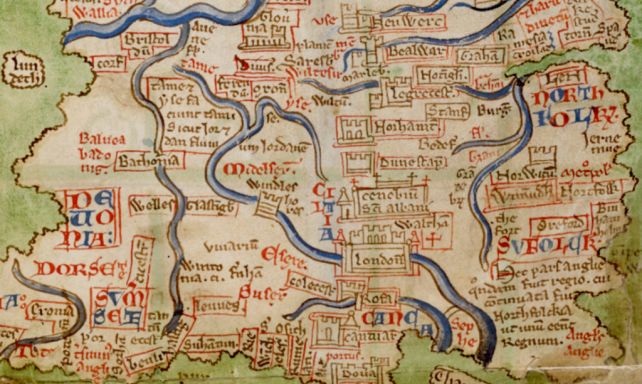

This information has been compiled into a newly relaunched, interactive website by Cambridge University’s Violence Research Centre. It’s called the Medieval Murder Map, where you can explore the map to learn the details of violent historical crimes.

“A medieval university city such as Oxford had a deadly mix of conditions,” says criminologist Manuel Eisner, lead murder map investigator and Director of Cambridge’s Institute of Criminology.

“Oxford students were all male and typically aged between fourteen and twenty-one, the peak for violence and risk-taking. These were young men freed from tight controls of family, parish or guild, and thrust into an environment full of weapons, with ample access to alehouses and sex workers.”

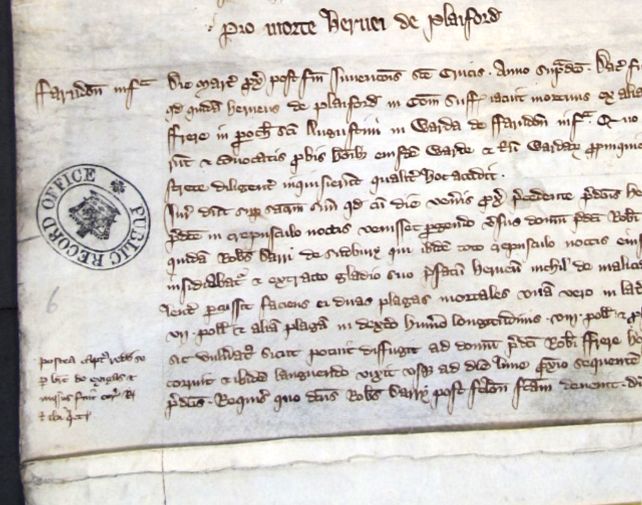

Originally launched in 2018, the Medieval Murder Map has received a significant update. Eisner and his team have translated and studied coroners’ rolls, records of investigations into violent crimes penned in Latin. These records included the who (perpetrator and victim, where known), the location, the weapon, and details of the crime.

The researchers then pinned these details to contemporaneous maps reconstructed by the Historic Towns Trust. The website now has the details of 354 murders across the three cities, with new details on accidents, sudden deaths, sanctuary church cases (in which the suspected felon would seek protection on consecrated ground to gain time for pleading their case with the coroner), and deaths in prison.

Murder cases in medieval England were treated in similar ways to how they are heard now.

“When a suspected murder victim was discovered in late medieval England the coroner would be sought, and the local bailiff would assemble a jury to investigate,” explains Eisner.

“A typical jury consisted of local men of good repute. Their task was to establish the course of events by hearing witnesses, assessing any evidence, and then naming a suspect. These indictments were summarized by the coroner’s scribe.”

It wasn’t guaranteed that the perpetrator would be brought to justice. But the crime rate in Oxford is certainly striking. Back then, the city had a population of around 7,000, with around 1,500 of those people students. Eisner and his colleague, historical criminologist Stephanie Brown of the University of Cambridge, worked out that the murder rate was around 60 to 75 people per 100,000 per year.

That’s huge, compared to England’s city murder rate today of less than 20 murders per million. The researchers say that the high crime rate is probably the result of a lot of young men gathered in one place (because women didn’t go to university), and a lot of booze. And ready access to weapons, of course.

“Knives were omnipresent in medieval society,” says Brown. “A thwytel was a small knife, often valued at one penny, and used as cutlery or for everyday tasks. Axes were commonplace in homes for cutting wood, and many men carried a staff.”

One murder recorded in Oxford took place after a gentleman took exception to another urinating on the street. The unfortunate victim was a servant unrelated to the disagreement. In another incident, a group of revelers took to the streets in the wee hours to sing and make merry; murder ensued when they refused to let a man they encountered join their party.

Sex workers could also be the victims of crimes, as with the case of one poor woman who, instead of being paid as requested, was violently killed.

“Circumstances that frequently led to violence will be familiar to us today, such as young men with group affiliations pursuing sex and alcohol during periods of leisure on the weekends. Weapons were never far away, and male honor had to be protected,” Eisner says.

“Life in medieval urban centers could be rough, but it was by no means lawless. The community understood their rights and used the law when conflicts emerged. Each case provides a glimpse of the dynamics that created a burst of violence on a street in England some seven centuries ago.”

You can peruse these cases in detail and at leisure on the Medieval Murder Map website.