Products You May Like

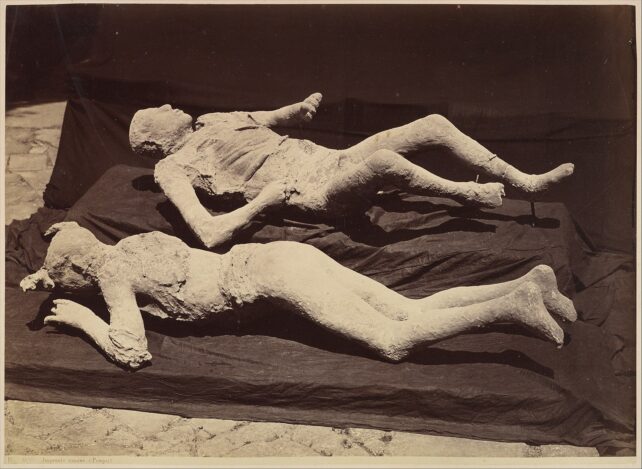

Personally witnessing the contorted forms of Vesuvius’s human and animal victims drives home the horror of their final moments like no words or footage ever could.

The famous casts of Pompeii have allowed this experience to be shared by generations of people across the world, from Italy to Australia.

Unfortunately, the plaster may have also contaminated the human remains within, a new study reveals.

Archeologist Llorenc Alapont of the University of Valencia in Spain and his colleagues believe plaster contamination is what’s made the biochemical analysis of these haunting remains so difficult, and why it’s been hard to conclusively confirm their actual cause of death.

“The use of plaster as a consolidant significantly affected the elemental profiles of some analyzed cast bones,” the researchers explain in their paper.

Over 100 casts were created in the 1870s by pouring plaster into voids of calcified volcanic ash left by decomposed bodies during the 79 CE volcanic eruption. The few remaining fragments of skeleton were embedded into the casts. It is these that researchers have attempted to assess to discover more about this doomed society.

Analyzing the chemistry of those remains using non-invasive X-ray fluorescence scanning for the first time, Alapont and team detected altered phosphorus and calcium concentrations in some of the bones.

This measure allowed them to determine which bones had been most contaminated. They were then able to identify remains with the least plaster interference for further analysis.

Their results supported previous theories, along with circumstantial evidence from the position of Pompei bodies and surrounding objects, about the tragic natural disaster that ended the once vibrant and thriving ancient metropolis of Pompeii.

While the plaster has altered the chemistry of the human remains it also helped preserve other information including the victims positions, even down to some of their expressions, and the presence of garments and other objects.

“They were laying on the ground trying to cover themselves with clothes, and with the fine ashes taking the shape of surrounding objects, including fine textiles,” Alapont and colleagues write.

This suggests the volcano’s victims, at least those that died in Porta Nola, were killed by asphyxiation from the gas and fine ash that burst from the collapse of the volcano’s lava dome. While not very hot, exposure to fine ash can only be tolerated for a few minutes even at low concentrations, the researchers explain.

This may have been a small mercy given what then followed: a brutal wave of incinerating gas and ash.

“The bodies under the high temperature (over 250˚C or 482˚F) of the ashes left by pyroclastic current suffered an “oven effect” and the “cooked” ashes left their fingerprint in a cavity, with just bones being left for many centuries,” explain Alapont and colleagues.

As a result, the bones’ chemical profile matches cremated individuals from the pre-eruption era. The cavities which held flesh before it was cooked and decomposed are what the future archeologists later filled with plaster.

“Our developed hypothesis for the cause of death is only applicable to the studied context. It is likely that the catastrophic eruption killed people in different ways,” the team qualify, noting that future analyses of the casts from other regions of Pompeii should also account for the plaster’s interference too.

This research was published in PLOS One.