Products You May Like

The biggest volcano in the Solar System could once have been an island in a vast sea, new research has found.

When Mars was young, and soggy, billions of years ago, the colossal Olympus Mons may have resembled Stromboli or Savai’i, but on a much larger scale.

A new analysis shows similarities with active volcanic islands here on Earth, adding to a growing body of evidence about Mars’ watery past.

“Here we show that the Olympus Mons giant volcano shares morphological similarities with active volcanic islands on Earth where major constructional slope breaks systematically occur at the sea-air transition in response to sharp lava viscosity contrasts,” writes a team led by geoscientist Anthony Hildenbrand of Paris-Saclay University in France.

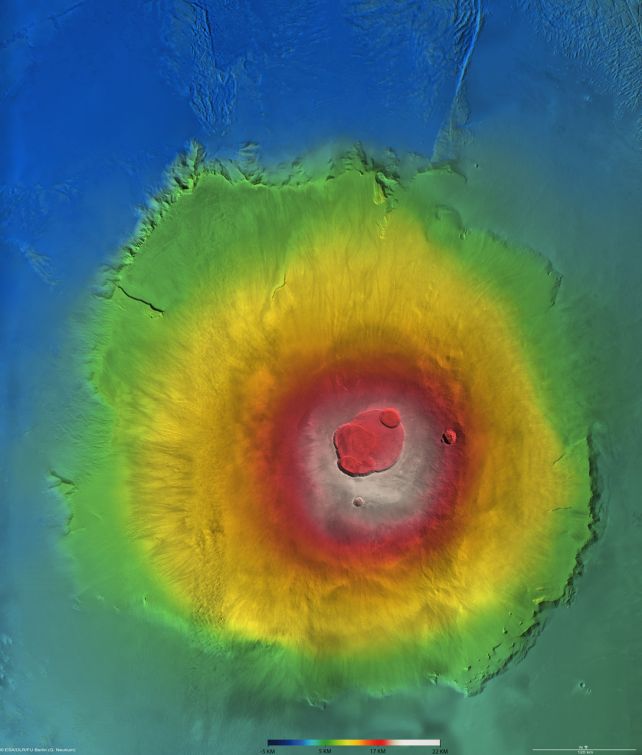

“We propose that the upper rim of the 6-kilometer high concentric main escarpment surrounding Olympus Mons most likely formed by lava flowing into liquid water when the edifice was an active volcanic island during the late Noachian–early Hesperian.”

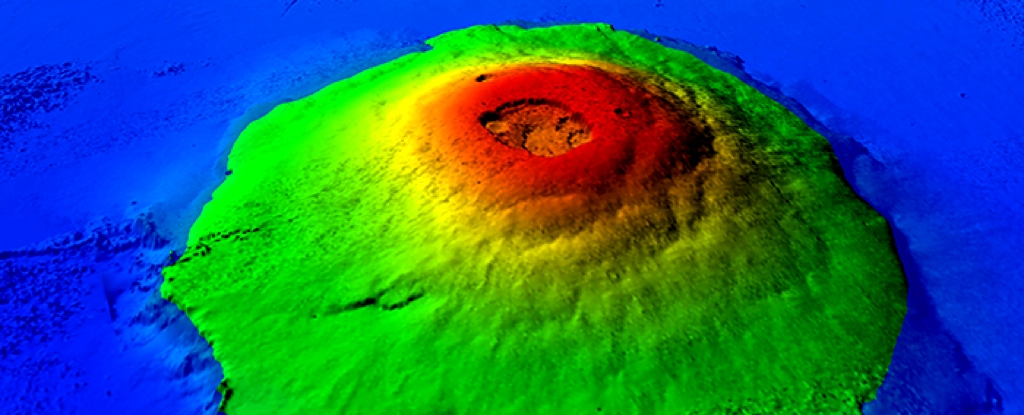

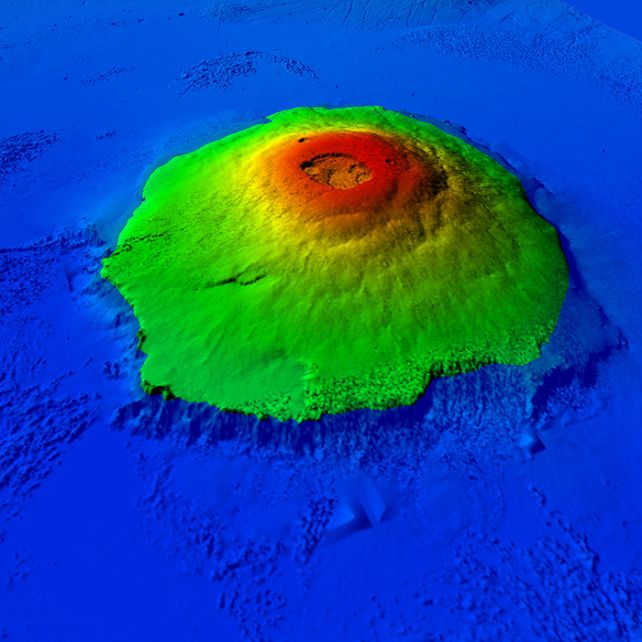

Olympus Mons is, however you measure it, a beast. The shield volcano stands approximately 25 kilometers (16 miles) high, and sprawls across an area roughly the size of Poland (or Arizona as another point of reference).

It’s not just the largest volcano, but the tallest planetary mountain known in the Solar System.

But there’s something odd about its foot. It doesn’t meet the ground as a clean slope. Rather, at a height of about 6 kilometers, for large portions of its circumference, it turns into a pronounced cliff, or escarpment, that drops off sharply to the surrounding landscape below. The origin of this feature is something of a mystery.

Mars is very dry and dusty nowadays. Any surface water is in the form of ice; no rivers flow, no oceans fill its vast basins and craters. But evidence continues to emerge that, once upon a time, Mars was rich with liquid water.

The Gale Crater, where Curiosity roams, appears to have been a vast lake, billions of years ago. Perseverance in the Jezero Crater explores a dried ancient delta.

Hildenbrand and his colleagues used this information to recontextualize Olympus Mons. They looked at similar shield volcanoes here on Earth. In particular, they studied three active volcanic islands: Pico Island in Portugal; Fogo Island in Canada; and the island of Hawaii in the US.

They found that the shorelines of these islands have sharp escarpments, similar to the escarpment that rings Olympus Mons. On Earth, these escarpments are the result of sharp contrasts in lava viscosity due to differential cooling as it transitions from air to water.

“This leads us to propose that Olympus Mons was a former volcanic island surrounded by liquid water,” the researchers write in their paper.

This could give us some clues about the water history of Mars. For example, the height of the escarpment would be the sea level of the long-lost ocean. And the age of the lava flows, dated to around 3.7 to 3 billion years ago, tells us when that ocean would have been there.

The team also identified similar features on another Martian volcanic mountain, Alba Mons, located more than 1,500 kilometers (932 miles) from Olympus Mons, across a vast expanse of lowlands.

This could mean that the waters of this ghost ocean filled large sections of the Martian surface.

The results give future Mars exploration missions a new avenue of enquiry regarding the history and evolution of Mars, the team says.

“Future spacecrafts dedicated to sample return and/or rover equipped for in-situ dating on selected sites of Olympus Mons constitute a promising line of research for the future, which can have significant impact regarding the longevity of oceans and the potential fate of early life on Mars,” the researchers write.

The research has been published in Earth and Planetary Science Letters.