Products You May Like

Some parasites have taken the simple life to whole new extremes.

Scientists have recently found a creepy, mind-controlling worm that is missing some of the most fundamental genes in the animal kingdom.

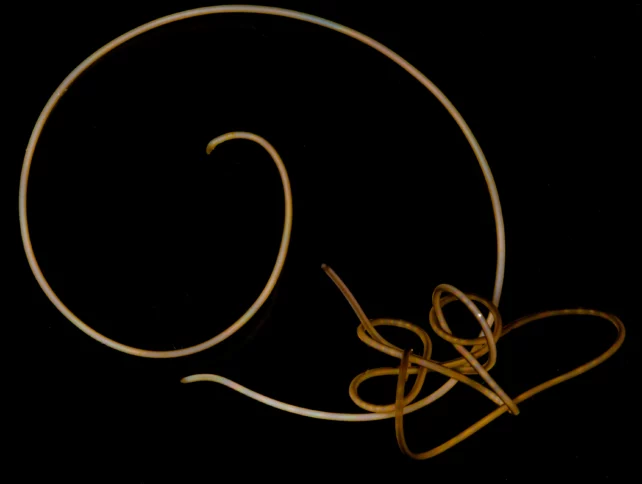

Ironically, the super long and thin ‘hairworm’ (also known as a ‘horsehair worm’) completely lacks the cellular-level ‘hairs’ that allow most animal cells to move, sense, or filtrate in liquids.

These microscopic filaments are known as cilia and they protrude from the surface of almost every cell in the human body.

Yet somehow, someway, two distant species of hairworm – one freshwater-based (Acutogordius australiensis) and one saltwater-based (Nectonema munidae) – have learned to live without these crucial appendages.

According to a team of researchers from Harvard University, the University of Copenhagen, and Chicago’s Field Museum, both species are missing about 30 percent of the genes thought to be responsible for the development of cilia across virtually all groups of animals.

The authors concluded that a distant common ancestor of hairworms must have shed these genes long, long ago. But why they did so remains a mystery.

“Cilia are organelles, small structures at the cellular level, that are basically present across all animals and even more broadly, in protists and some plants and fungi,” explains Field Museum evolutionary biologist Tauana Cunha.

“So they’re present across a large diversity of life on Earth.”

But the hairworm is special.

In the animal kingdom, it’s not uncommon for parasites to be missing lots of genes. Similar to the hairworm, many of these creatures have no excretory, respiratory, or circulatory systems. Instead, they rely on the bodies of other animals to do most of the hard work.

In evolutionary biology, if an animal doesn’t ‘use’ a structure or function, they tend to lose it gradually as they reclaim the cost of it requires.

To have zero genes for cellular cilia, however, is astonishing. Even the hairworm’s sperm lack a tail-like filamentous projection.

“There are plenty of other parasitic organisms that aren’t missing these specific genes, so we cannot say that the genes are missing because of their parasitic lifestyle,” says Cunha.

Researchers had previously noticed that hairworms didn’t have cilia in some cells. But until now, it wasn’t clear if this pattern existed across all the parasite’s cells in all its various life stages.

“Now with the genomes, we saw that they actually lack the genes that produce cilia in other animals– they don’t have the machinery to make cilia in the first place,” explains Cunha.

“It is likely that the loss happened early on in the evolution of the group, and they just have been carrying on like that.”

The authors hope their study will help scientists further probe the “genomic mechanisms underlying parasitism” to reveal how these wacky creatures pull off their fully-body heists.

After invading a cricket’s brain, maturing hairworms eats the insect from the inside out, sparing just enough of its body to keep it alive.

Once they’ve had their fill, the hairworm hotwires the cricket’s nervous system, moving the host body in twitches toward a body of water.

Once its grim puppet is submerged, the worm jumps ship, crawling out of the cricket’s body in long wriggling tendrils so it can reproduce.

It’s possible something in this macabre reproductive process requires specialized sensory organs that have no use for cilia. No doubt future investigations into this strange puppet-master will continue to show why it is thankfully so unique.

The study was published in Current Biology.