Products You May Like

There are many ways we humans have unleashed devastation on each other – nuclear weapons, pollution, the spread of deadly pathogens, just to name a few.

While it’s hard to say with certainty, by many accounts the deadliest day in human history was actually the result of a natural disaster. On the morning of 23 January 1556, a massive earthquake rocked China’s Shaanxi province, at the time considered the ‘cradle of Chinese civilization‘.

The quake only lasted a few seconds but is estimated to have directly killed 100,000 people, with the ensuing cascade of landslides, sinkholes, fires, migration, and famine killing an estimated total of 830,000 people.

Of course, that’s nowhere near as high as the total death tolls of major events like WWI and WWI, or even pandemics, famines, or floods.

But when considering a single day of devastation, the Shaanxi earthquake – also known as the Jiajing earthquake because it struck under the reign of the Jiajing Emperor of the Ming dynasty – is widely considered the most fatal we know of. It’s also listed as the deadliest recorded earthquake in history.

The event is only thought to have had a magnitude of 8.0 to 8.3. Many more powerful earthquakes have occurred both before and afterwards. But due to the geology and urban design of the area at the time, it caused disproportionately massive destruction to the surrounding cities of Huaxian, Weinan, and Huayin.

The Local Annals, which according to History.com date back to 1177 BCE, describe the destruction caused by the quake in rare detail.

A translated quote from the Annals claims that mountains and rivers changed places.

“In some places, the ground suddenly rose up and formed new hills, or it sank abruptly and became new valleys. In other areas, a stream burst out in an instant, or the ground broke and new gullies appeared. Huts, official houses, temples and city walls collapsed all of a sudden.”

It’s recorded that fissures opened up in the ground that were more than 18 meters (60 feet deep).

In Huaxian, every single building reportedly collapsed and close to the epicenter, about 60 percent of the population was killed.

Despite its relatively low magnitude, the quake is listed as XI (Extreme) on the Modified Mercalli intensity scale, which measures the intensity or shaking of an earthquake.

What made the earthquake so deadly?

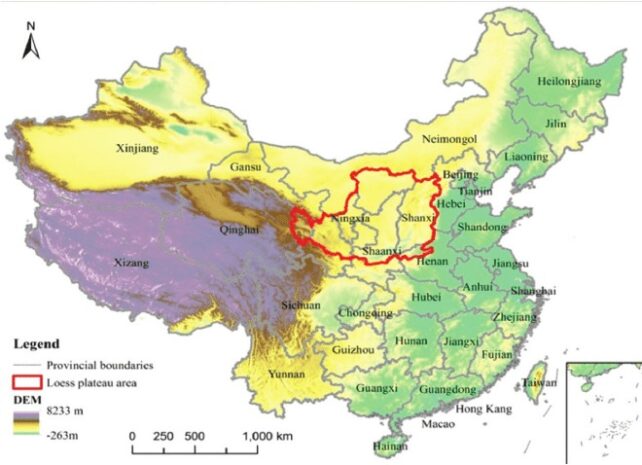

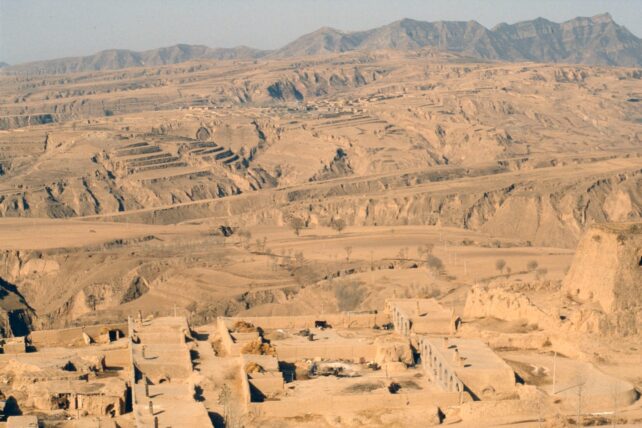

The epicenter was in the Wei River Valley which is geologically unique because it runs across the Loess Plateau in north-central China. Sitting below the Gobi Desert, the plateau is formed from loess: a silt-like sediment formed by the build up of wind-blown dust that’s eroded from the desert.

The plateau is now known for having regular, deadly landslides. But at the time, many houses were built directly into the soft loess cliffs, making artificial caves known as yaodongs.

When the earthquake hit in the early hours, many of those yaodongs collapsed, burying those inside and causing landslides that spread across the plateau.

It wasn’t just the yaodongs, but many of the buildings in the cities were made of heavy stone at the time, which caused a lot of destruction when they collapsed.

What caused the earthquake?

There are three major fault lines running through the area: the North Huashan fault, the Piedmont fault, and the Weihe fault.

A 1998 geological analysis of the 1556 quake concluded that the North Huashan fault played an important role in the event, “because its scale and displacements are the largest in the study area.”

“We need to consider the potential for active faulting, and prepare for another possible large earthquake in the region, since the faults are active now,” the researchers from Peking University concluded.

According to History.com, the Shaanxi earthquake actually inspired a search for the causes of earthquakes, and ways to minimize future damage caused by such disasters – stone buildings were replaced with softer, more earthquake-resistant materials, such as bamboo and wood.

As humanity hurtles ever closer to new ecological and anthropogenic disasters, it’s somewhat humbling to think that the deadliest day could not be triggered by us, but rumblings deep within our planet.