Products You May Like

Science is founded on hard evidence, but ironically, many of the stories we tell about scientists and their experiments are not based on much truth.

An apple falling on Newton’s head didn’t suddenly stimulate his idea of gravity; Darwin’s theory of evolution wasn’t founded on the beaks of finches.

And Benjamin Franklin certainly didn’t discover electricity by holding a kite in a storm.

It’s hard enough to imagine a great scientific mind standing in an open field, trying to attract a bolt of lightning to a metal key without any insulation or protection whatsoever – let alone one that would put a child in danger’s way, too.

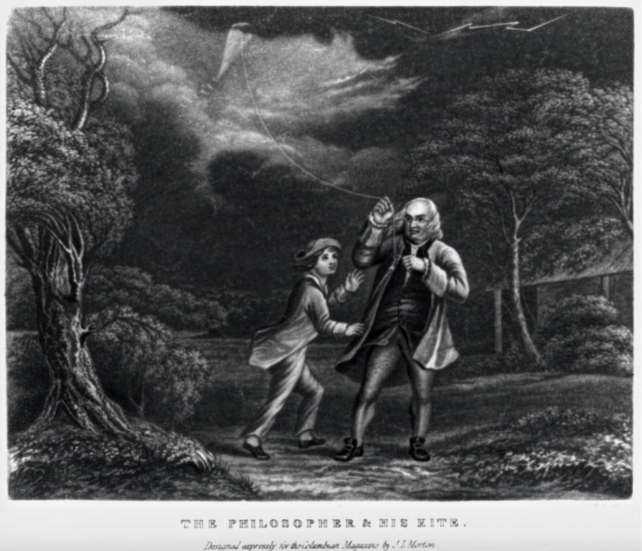

But that’s what many illustrations of Franklin’s kite experiment, including the one below, would have you believe.

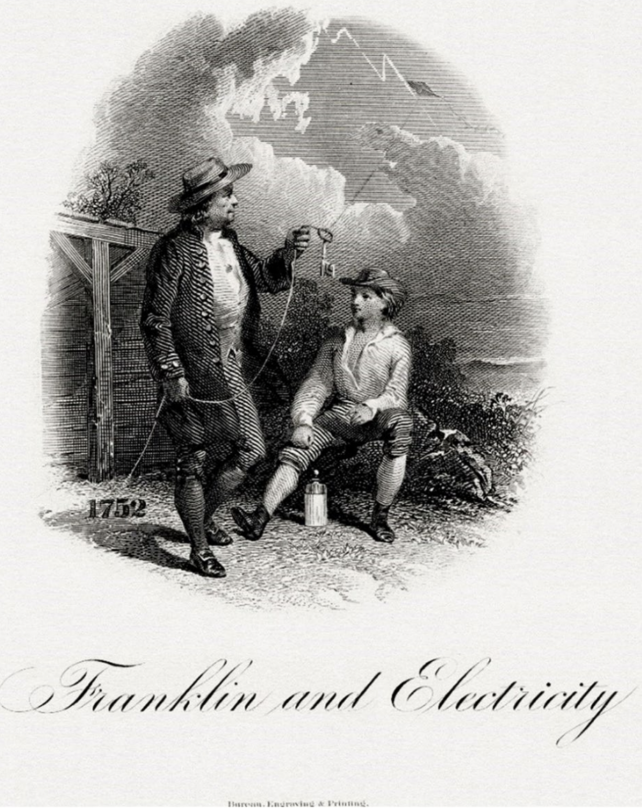

These images weren’t intended to be educational, yet they appear extensively in textbooks, documentaries, and even by scientific institutions like the Royal Society of London.

The science historian Breno Arsioli Moura wants to set the record straight.

With support from the São Paulo Research Foundation and the Federal University of the ABC in Brazil, he analyzed seven illustrations of Franklin’s kite experiment that were made in the 19th century.

The inaccuracies are laughable.

These images, he says, are primarily based on secondhand evidence and present “serious errors regarding the transmission of electricity, the role of conductors and insulators, and the protection of the experimenter.”

First, despite what you might remember being told at school, Franklin never wanted lightning to hit his kite. Even then, he would have known of the fatal consequences.

No, this experiment was carefully thought out by Franklin to determine if “the clouds that contain lightning are electrified or not”. Scientists already knew of electricity.

Franklin was just trying to prove that there was an ambient electrical charge to the clouds above.

Carefully positioned under cover, the famous scientist suggested that if someone flew a kite with a metal rod during a rainstorm, electricity in the sky could travel down the rain-soaked kite string to an attached metal key.

A silk string would separate the person flying the kite from the electricity. However, as they brought their finger closer to the metal key, they should be able to sense a tiny spark.

The famous experiment is logically sound, but whether Franklin ever actually carried it out is unknown.

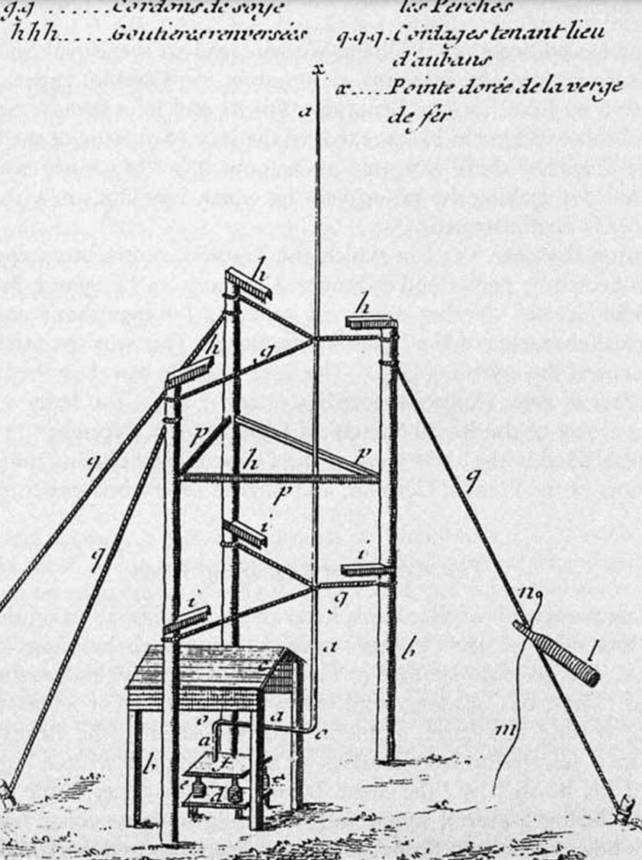

The scientist barely mentions the kite idea in his autobiography. Instead, he talks mostly of the ‘sentry box’ experiment, a similar idea he had that relied on a large metal rod stretching up into the sky, connected to a small electrical conductor in a nearby shelter.

“It’s important to note two things,” explains Moura. “The experiment wasn’t to be performed during a storm to take advantage of lightning strikes, and the rod wasn’t to be earthed but anchored by the insulating stand so that all the electricity extracted would be stored in it.”

The only other source for the kite experiment is a report written by a historian named Joseph Priestley in 1767. In it, Priestley says that Franklin secretly told his son about the experiment because he was worried it wouldn’t work. Apparently, the author had it “from the best authority” that Franklin’s son assisted him in raising the kite in June 1752.

According to Moura, Priestley’s account seems to be the primary source on which many later illustrations were based.

Since Priestley mentioned Franklin’s son, for instance, a child often appears in the drawings and etchings, although curiously, this kid looks much younger than 21 years old, the age of Franklin’s son at the time.

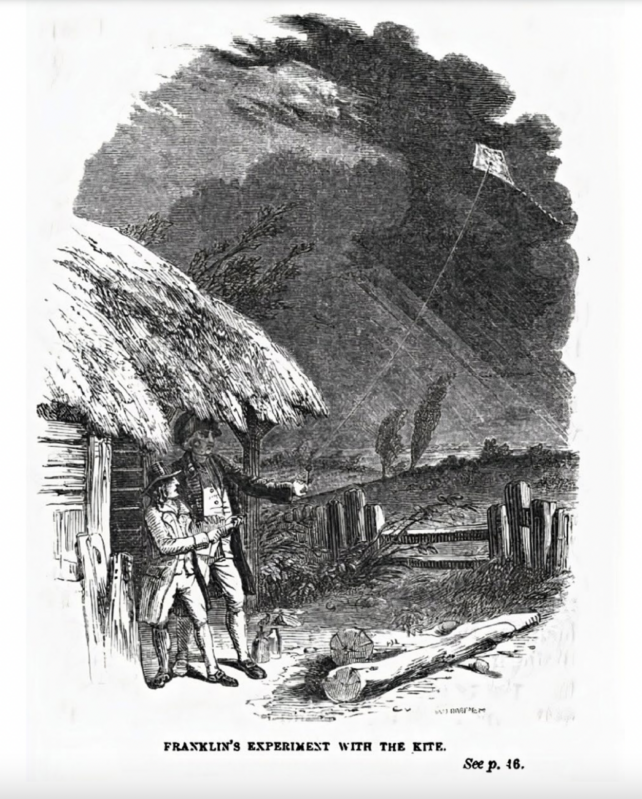

Moreover, since Priestley did not emphasize the importance of shelter in his account, almost all the illustrations have Franklin and his son standing in an open field. Only once are they depicted huddling under the cover of a thatched roof.

Other times, it’s the key that is missing. Rarely is Franklin illustrated using any insulation when holding the kite. Both are crucial details.

The earliest illustration analyzed by Moura, entitled The Philosopher and His Kite, actually depicts Franklin holding the kite string above the key.

This would have ruined the whole experiment as it meant the metal object would be grounded and couldn’t conduct a spark.

“Worse yet,” writes Moura, other illustrations suggest that lightning actually struck the kite or somewhere near it, “which would certainly have killed both Benjamin and William Franklin.”

The misinterpretation might stem from Priestley inaccurately describing electricity flowing down Franklin’s kite string as ‘lightning’.

Historian Alberto Martinez is an expert on the mythology behind scientific discoveries, and he says the Franklin story is one of his favorites.

“Regardless of its truth or falsehood, it’s fascinating to imagine this guy having the courage and stupidity to fly a kite in a thunderstorm and that he used a child’s toy to draw ‘electrical fire’ from the sky,” Martinez explains.

“It has the shape of a classic myth: the story of Prometheus, who used a long stalk of fennel to steal fire from the god of sky and thunder.

But Moura sees it a bit differently.

He thinks that when we see illustrations of the kite experiment in a Ken Burns documentary, we fail to see the “intriguing details” and overlook the “scientific errors”.

“There are far more complex and interesting histories behind what they intend to represent,” says Moura.

They say you should never let the facts get in the way of a good story, but sometimes, revealing the truth is the better story after all.

The study was published in Science & Education.