Products You May Like

Anemia was common in mummified ancient Egyptian children, according to a new study that analyzed child mummies in European museums.

Researchers used computed tomography (CT) scans to peer non-invasively through the mummies’ dressings and discovered that one-third of them had signs of anemia; they found evidence of thalassemia in one case, too.

“Our study appears to be the first to illustrate radiological findings not only of the cranial vault but also of the facial bones and postcranial skeleton that indicate thalassemia in an ancient Egyptian child mummy,” the team writes in their published paper.

Paleopathologist Stephanie Panzer and her colleagues from Germany, the US, and Italy, suggest that anemia was likely common in ancient Egypt, and it was probably caused by factors such as malnutrition, parasitic infections, and genetic disorders, which still cause the health problem today.

Researchers have even speculated that Tutankhamun died of sickle cell disease, a cause of anemia. However, as the researchers of this new study explain, “the direct evidence of anemia in human remains from ancient Egypt is rare.”

Anemia is a condition where the body lacks enough healthy red blood cells to carry oxygen to the body’s tissues. As Panzer and colleagues studied child mummies, the remains are more likely to show signs of anemia than adult mummies, due to their early death.

Whether or not anemia played a role in each of the children’s deaths could not be determined from the CT scans, but the research team believes it is likely to have contributed. They also looked for signs of diseases that could have caused the anemia.

When ancient humans were mummified, their bodies were preserved in ways that kept more information than those buried. Although modern science doesn’t let researchers remove the wrappings used in the mummification process, they often use scans to ‘look’ through the wrappings and see what’s inside.

CT scans can look at the mummies’ bones, which can provide evidence of anemia because the bone marrow makes red blood cells.

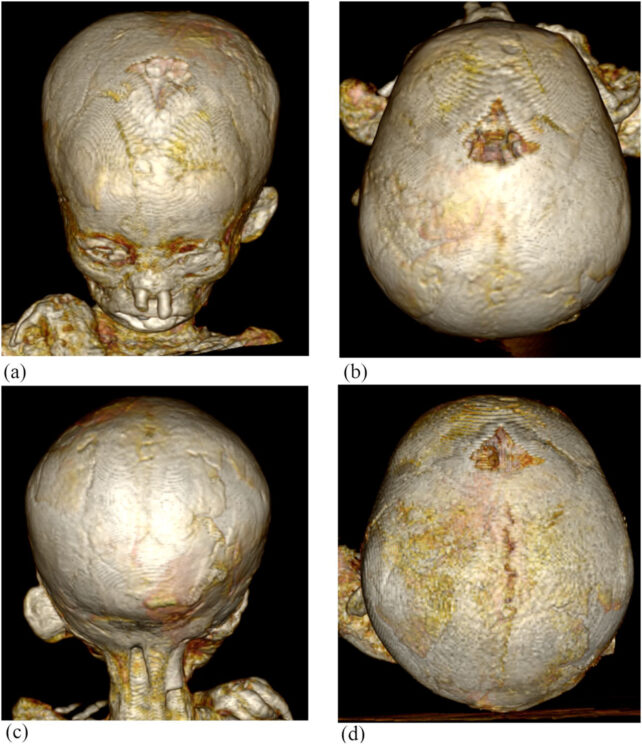

Chronic hemolytic anemia and iron deficiency anemia are often accompanied by an enlargement of the cranial vault (the area of the skull that houses the brain). The researchers hoped to look for this along with further indicators of anemia in the bones, such as porosity, thinning, and changes in shape.

Measuring the porosity and thinness of bones requires a certain level of contrast – often reduced in the CT scans by the density of the preserved tissue and surrounding embalming. After consideration, this assessment, as the authors explain in their paper, “was not feasible in this study because of insufficient CT image quality.”

Overall, the team found that 7 of the 21 child mummies they examined in German, Italian, and Swiss museums had measurable signs of anemia, specifically an enlarged frontal cranial vault.

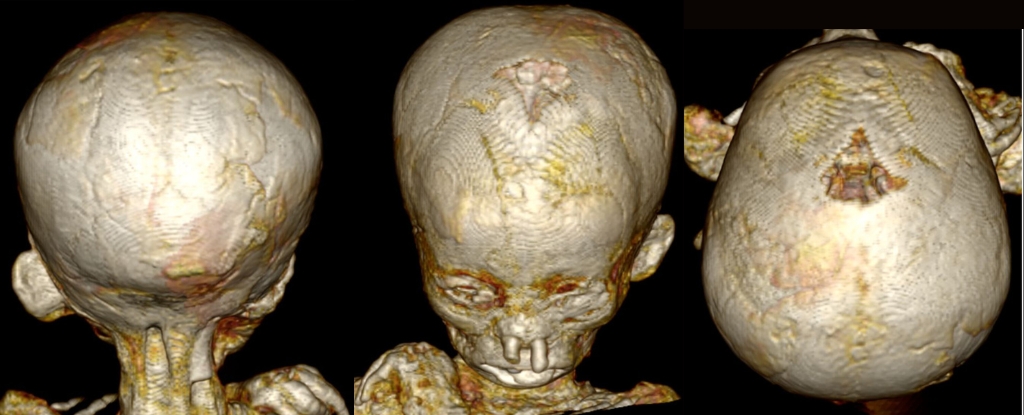

Moreover, one child – referred to as case 2 – had facial and other bone changes present in thalassemia, a genetic disease in which the body can’t make enough hemoglobin. Case 2 also had a tongue that was larger than usual, which the authors say “probably indicated Beckwith–Wiedemann syndrome.”

This genetically unlucky child probably died from thalassemia’s many symptoms, which can include anemia, within 1.5 years of birth.

The mummified children, estimated to be aged between 1 and 14 years when they died, lived during multiple periods.

“The chronologically oldest mummy dated back to the time span between the Old Kingdom (2686–2160 BCE) and the First Intermediate Period (2160–2055 BCE). Most mummies dated to the Ptolemaic (332–30 BCE) and Roman Periods (30 BCE–395 CE),” the researchers state.

As sad as this discovery is, ancient Egyptian mummified remains certainly have revealed some interesting facts and insights about their lives and deaths. While it adds to our understanding, a small-scale study like this does have limitations.

“The collection of investigated child mummies did not represent a population,” the authors note in their paper.

“The purpose of this study was to estimate the prevalence of anemia in ancient Egyptian child mummies and to provide comparative data for future studies.”

The study has been published in the International Journal of Osteoarchaeology.