Products You May Like

Researchers have just calculated the value society gets from a common but hidden underwater resource, and found it’s way higher than we ever expected.

Kelp forests have long done so much for humanity, all the while operating out of sight beneath the waves.

Hugging a third of our coastlines, they provide food and homes for much of our coastal seafood. In doing so, these vibrant ocean jungles aided daring human migrations like the southward colonization of the Americas 20,000 years ago.

We also eat the kelp itself, use it to fertilize crops, add it to medicines and skincare, and breathe the oxygen it produces.

Yet kelp forests are in a catastrophic decline, and we don’t fully understand the extent, let alone the value, of what we’re losing. So a team of researchers tallied an estimate of the services kelp ecosystems provide us all.

“For the first time, we have the figures to demonstrate the considerable commercial value of our global kelp forests,” says University of New South Wales marine ecologist Aaron Eger.

“We found 740 million people live within 50 kilometers of a kelp forest. So these systems have a significant role to play in supporting these people’s livelihoods and vice-versa.”

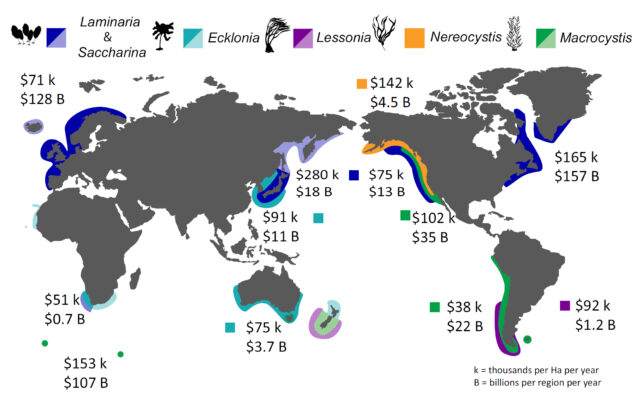

Eger and colleagues used 1,354 fish and invertebrate surveys across six different types of kelp forests in eight different ocean areas. They also took measures of nutrient use from carbon to phosphorus.

The economic value of kelp forest contribution to fisheries production averages USD $29,851 and 904 kilograms per hectare per year, the team reports.

Surprisingly, only 50 types of animals out of the 193 identified contributed the bulk of value to fisheries, primarily invertebrates such as lobsters, urchins, and abalone.

Not only do these ocean ‘trees’ provide habitat for thousands of marine species, but they also play a huge role in global nutrient cycles too. Kelps are a type of algae that are protists, not plants, but just like plants, their photosynthesis puts energy into the webs of life they shelter, removing carbon dioxide from their environment and producing oxygen in the process.

Removing carbon dioxide, in turn, elevates pH levels and oxygen supplies in the immediate areas – helping mitigate the local effects of ocean acidification.

Kelps also take up other nutrients, like nitrogen and phosphorus, to fuel their rapid growth, with some species able to add up to 50 centimeters of height in a day. Previous research found kelp forests are even more productive in terms of growth than intensely farmed crops like rice and wheat.

“Of the three elements, nitrogen removal provided the highest economic value per hectare per year (mean = USD $73,831, 620 kilograms), followed by phosphorus removal (mean = USD $4,075, 59 kilograms), and lastly carbon capture (mean = $163, 720 kilograms),” Eger and colleagues write.

While kelp’s carbon uptake may not be as impressive as its nitrogen removal, it’s still equivalent to land forests and seagrasses.

“Globally, these kelp forests produce an estimated average USD $500 billion per year,” the team concludes. This is three times more than the previous best estimates and is only a baseline measure that has yet to consider other significant contributions to our economy.

“There were also many other services we didn’t assess, including tourism, educational and learning experiences, and kelp as a source of food, so we anticipate the actual value of kelp forests in the world to be higher,” Eger qualifies.

Kelp also has incredible potential as a sustainable biofuel and helps protect our coasts from eroding.

But like far too much of the world around us, kelp forests are struggling. In the last few decades, about a third of all kelp forests have suffered deep losses. A combination of heat waves and ravenous invasive sea urchins has seen a 95 percent decline in kelp off California’s coastline since 2014. Half a world away, Australia’s kelp forests have been listed as endangered after similarly drastic declines.

They also suffer from pollution from human activities, and as these floating forests decline, so do lobsters, abalone, fish, and all the other life counting on their existence.

“Putting the dollar value on these systems is an exercise to help us understand one measure of their immense value,” Eger says. “It’s important to remember these forests also have an intrinsic, historical, cultural, and social value in their own right.”

The researchers hope their findings will draw some much-needed attention to this long-neglected ecosystem. They are fighting to restore and protect millions of hectares with a global Kelp Forest Challenge.

This research was published in Nature Communications.