Products You May Like

Increasingly tempestuous winds have been sweeping dust from Earth’s deserts into our air at an increasing rate since the mid-1800s. New data suggests that this uptick has masked up to 8 percent of current global warming.

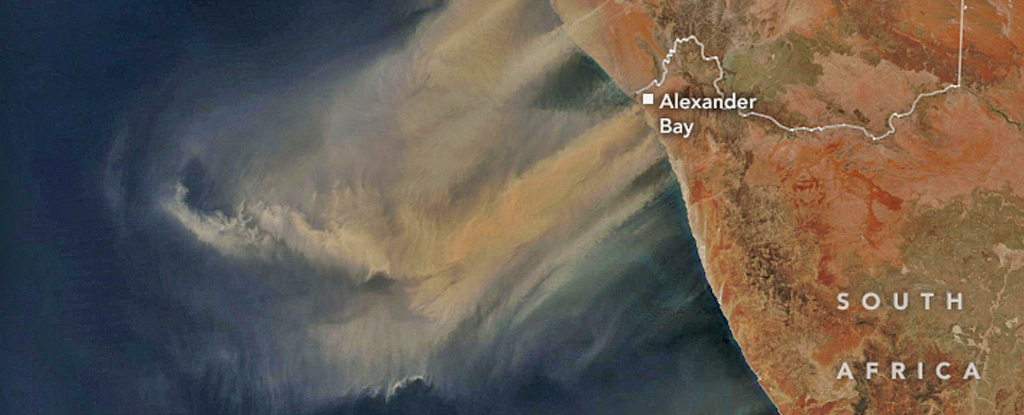

Using satellite data and ground measurements, researchers detected a steady increase in these microscopic airborne particles since 1850. Soil dust in ice cores, ocean sediments, and peat bogs shows the level of mineral dust in the atmosphere grew by around 55 percent over that time.

By scattering sunlight back into space and disrupting high-altitude clouds that can act like a blanket trapping warmer air below, these dust particles have an overall cooling effect, essentially masking the true extent of the current extra heat energy vibrating around our atmosphere.

Atmospheric physicist Jasper Kok from the University of California, Los Angeles, explains that this amount of dust would have decreased warming by about 0.1 degrees Fahrenheit. Without the dust, our current warming to date would be 2.3 degrees Fahrenheit (1.2 degrees Celsius).

“We show desert dust has increased, and most likely slightly counteracted greenhouse warming, which is missing from current climate models,” says Kok. “The increased dust hasn’t caused a whole lot of cooling – the climate models are still close – but our findings imply that greenhouse gases alone could cause even more climate warming than models currently predict.”

Higher wind speeds, drier soils, and changes in human land use all influence the amount of dust swept into our atmosphere. Some of this then falls into our oceans, feeding important nutrients like iron to photosynthesizing plankton that draw down carbon as they grow and reproduce.

This complicated desert dust cycle has yet to be factored into our climate models, and whether or not the amount of desert air particles will increase or decrease in the future is still unclear.

“By adding the increase in desert dust, which accounts for over half of the atmosphere’s mass of particulate matter, we can increase the accuracy of climate model predictions,” says Kok. “This is of tremendous importance because better predictions can inform better decisions of how to mitigate or adapt to climate change.”

This research was published in Nature Reviews Earth and Environment.