Products You May Like

What is going to happen to the 15,000 colorful electric scooters that currently spill across the streets of Paris? On March 23rd, their fate could drastically change as the French capital weighs up whether or not to renew licenses for the three scooter companies currently operating in the city.

And this isn’t just going to impact Dott, Tier and Uber-affiliated Lime — the three companies that have held those licenses since 2020. The decision will set a precedent for the many cities around the world that have also let scooters onto their streets. If things don’t go their way, a negative decision in Paris could have a chilling effect on micromobility startups globally.

Paris has been a pacemaker in the electric scooter race. As one of the first cities to approve their use in open city environments, city residents (and visitors) took to them as a convenient way to navigate around halting traffic and congested public transport; scooters in Paris provided a counterpoint to the claims that they were overhyped, over-capitalized by unimaginative VCs and a flash in the pan.

“This is important for everyone. In terms of business size, Paris is very important — it’s the biggest city in the world from a business point of view,” Dott’s director of marketing and communications Matthieu Faure told me. “And even from a symbolic point of view, Paris is important.”

Things started to look shaky starting in September 2022, when the city’s Deputy Mayors David Belliard and Emmanuel Grégoire requested a meeting with the three mobility operators. They said that Dott, Lime and Tier weren’t doing enough when it came to safety and urban clutter. But this wasn’t the first time the city of Paris had said it wasn’t satisfied with these services.

From the word go, there was no proper regulation in place and initially that led to a dozen different scooter startups rolling out their fleets in Paris — Bird, Bolt, Bolt by Usain Bolt (oui, deux Bolts), Circ, Dott, Hive, Jump, Lime, Tier, Voi, Ufo and Wind.

That eventually led to the tender process and a new set of rules — a maximum speed limit of 20 km/h and some dedicated parking spaces.

Then in 2021, tragedy struck when a pedestrian was killed in a scooter accident. That led to more restrictions on scooter services. Scooter companies agreed to implement hundreds of slow zones with a 10 km/h speed restriction in specific areas — pedestrian streets, public squares and car-free areas. At one point, the city of Paris even considered turning the entire city into a slow zone but ditched the plan.

There’s also the climate change question — and whether that’s really enough of a selling point. Scooter promoters like to say they are a green option for getting around. But as TechCrunch’s Rebecca Bellan has pointed out, scooters aren’t necessarily helping when it comes to environmental goals in certain urban areas. Such is the case in Paris.

An extremely dense city with an efficient subway network and a subsidized bike-sharing service with more than 400,000 subscribers, when people living in Paris need to go from A to B, they have a ton of options. Some people riding on electric scooters would have used their moped or requested an Uber, but many use scooters instead of the metro, which is arguably a greener mode of transportation compared to electric scooters.

And yet, both tourists and Parisians have embraced electric scooters in a massive way.

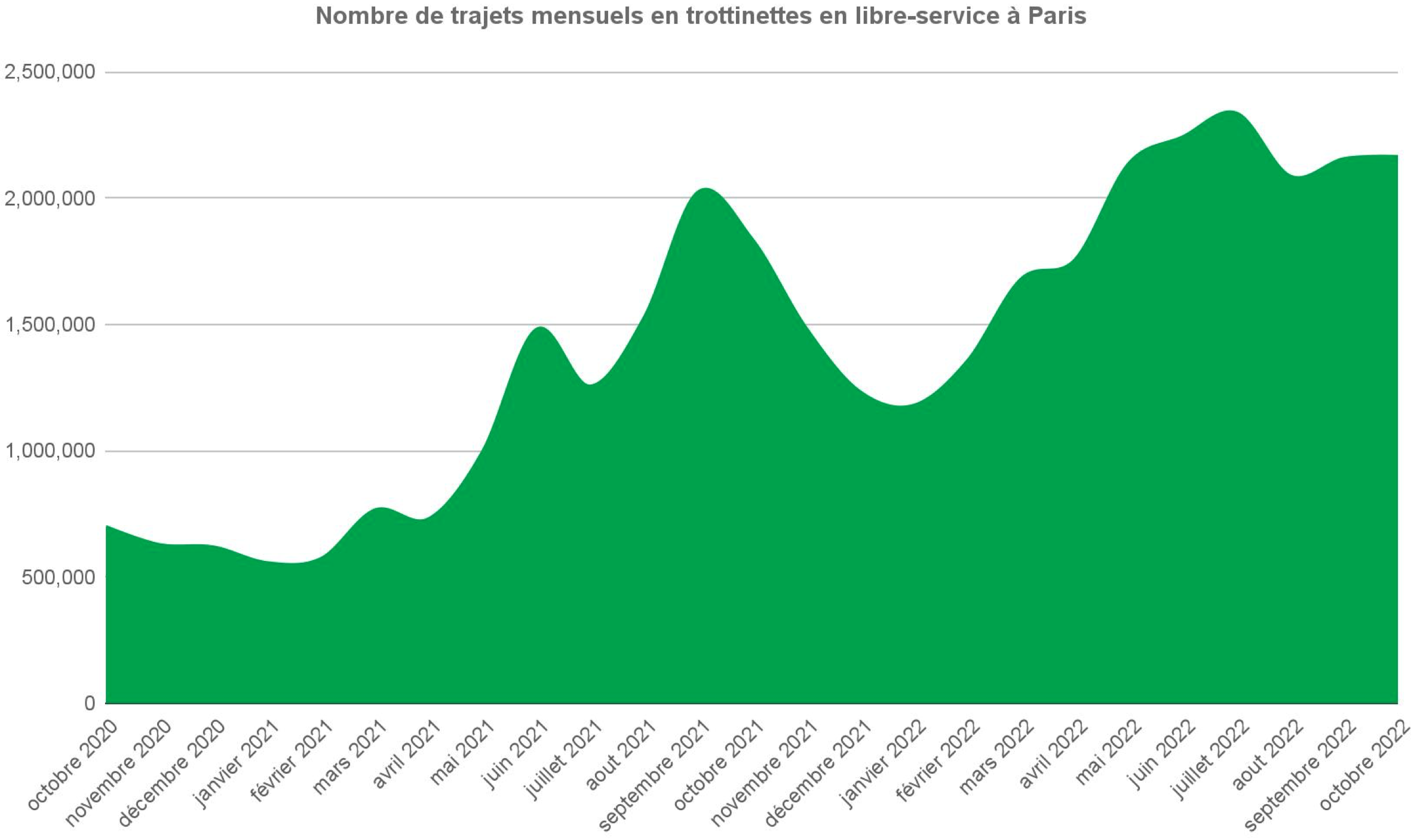

In October 2022, Dott, Lime and Tier registered more than 2 million rides. Out of the 400,000 users spread across the three services in Paris, 85% of them live in the city.

Operators each have a hard cap at 5,000 scooters, meaning there are roughly 15,000 scooters on the streets of Paris. According to Fluctuo, there are close to 300,000 shared scooters in 33 European cities.

But each scooter is used quite extensively in Paris — several times per day. Here’s a chart of the total number of scooter rides per month in Paris:

Image Credits: Dott, Lime, Tier

The promise of metrics like these has led to massive valuations and funding rounds. According to Crunchbase, to date, Lime, one of the companies that popularized the concept of free-floating scooters, raised $1.5 billion. Dott managed to secure $210 million while Tier grabbed nearly $650 million.

To be sure, it’s been mostly quiet on the funding front for these companies for much of the last year. Partly this is because the most publicly visible of these companies, Bird, which pointedly is not in Paris but is traded on the NYSE, has totally run out of charge. (With its market cap now at less than $86 million — compared to more than $2 billion when it went public in March 2021 — last week Bird announced a $32 million cash injection by way of convertible notes and personal investments from founder and chairman Travis VanderZanden and CEO Shane Torchiana. The money came at the same time that Bird acquired the previously spun-out Bird Canada and made other moves to try to shore up its finances.)

Turning back to Paris, following the September 2022 meeting, the three active scooter companies (Lime, Dott and Tier) got the civic message: they shouldn’t take for granted that scooter licenses would be renewed in 2023. With the wider market climate definitely not in their favor, proving that they are respectful companies in their marquee city became priority number one.

In October 2022, the three operators put together a list of 11 proposals that would improve safety and public space integration, ranging from banning users who do not respect the road-traffic regulations to using camera-based sidewalk detection systems.

Dott, Lime and Tier even started implementing some of those items. They added an age verification system and asked its users to take a photo of their ID. Similarly, there is now a registration plate on every scooter. This way, if there are two people riding a scooter at the same time, the police can write down the registration plate and the current time. Scooter companies can then find out who was using a specific scooter at that specific time.

“We’ve decided in December to proactively roll out two of these, notably on ID verification and license plates. After 30 days, we now have 100% of shared e-scooters in Paris that have a license plate, and over 160,000 IDs have been verified and checked,” Erwann Le Page, director of public policy for Western Europe at Tier, told me.

And then what happened? Nothing happened.

The negotiation tactic of silence

The city of Paris is divided on scooter regulation. Deputy Mayor David Belliard has been one of the most vocal opponents. He regularly claims that scooters should be banned, and his words carry weight: among other things, he’s in charge of transportation.

But the fact that he’s using media interviews to say that scooters should be banned proves that not everyone in the city council agrees with him.

“It’s a personal opinion, he’s against shared scooters,” Dott’s Matthieu Faure said. “We don’t really understand why. He doesn’t give any rational explanation.”

In particular, what does Anne Hidalgo, the Mayor of Paris, think about scooters? Nobody knows for sure.

“The City Council has not communicated any decision yet. To date, the City has not responded to any of the meeting requests and letters sent by Lime or the two other operators,” a Lime spokesperson told me.

“We have not heard back from Paris just yet. Our contract ends on March 23rd,” Tier’s Erwann Le Page added.

We have asked the city of Paris for a comment, and we will update the story if we hear back.

Image Credits: Lime

If I read correctly between the lines, Anne Hidalgo will ultimately have to decide whether scooter licenses should be renewed. Everything else you hear on this topic is just noise.

And there is no reason to communicate with scooter companies just yet. Scooter companies are already improving the safety of their services because the mayor of Paris is remaining silent.

In other words, saying nothing is the best strategy to get improvements from operators right now.

Reducing dependence on scooters in Paris

In contrast to the early days of shared scooters, micromobility companies have mostly switched to full-time employees to repair, replace and move vehicles and swap batteries.

There are currently 800 people working for Dott, Lime and Tier in Paris. There are another 200 people working indirectly with the three operators. In particular, a subcontractor company patrols the streets of Paris and works with all three companies.

And this model has been working well. Dott says that it is currently profitable in Paris when you take into account all fixed and variable costs associated with its Paris operations, including vehicle depreciation and amortization (EBIT profitable).

While Dott, Lime and Tier are currently live in dozens of cities, Paris still represents a good chunk of these companies’ revenue. That’s probably why they decided to launch bike-sharing services with free-floating electric bikes.

“We are currently operating 7,000 [bikes] in Paris and we plan to continue doing so,” a Lime spokesperson told me. Similarly, Dott has a fleet of 3,500 bikes, while Tier manages 2,500 electric bikes.

This time, there was no tender process for free-floating bikes, but operators still had to sign an agreement with the city of Paris. They also pay a license fee.

Image Credits: Dott

Adding electric bikes is a smart move, as there are some synergies between scooters and bikes. For instance, Lime uses the same batteries for its scooters and bikes, meaning that the operations team can swap batteries for all vehicles when roaming the streets of Paris.

But it’s clear that Dott, Lime and Tier still want to offer scooters after March 23rd. On Wednesday, a group of employees working for Dott, Lime and Tier protested in front of the city hall. They were asking for a meeting with city officials to get some clarity.

Once again, their demands were met with silence. Even if the city of Paris doesn’t seem to care about media coverage on the license renewal, the impending deadline means that the mayor of Paris will have to make a decision sooner rather than later. And many micromobility companies and local governments are turning their attention to what that answer will be.

Image Credits: Tier Mobility