Products You May Like

Take one look at Italy’s Leaning Tower of Pisa and a single question springs to mind: just how close is it to toppling right over?

For decades going on centuries, engineers, historians, and onlookers have held their collective breath at the fate of the iconic bell tower, which has weathered four earthquakes and swayed back and forth, yet somehow still stands with that eponymous lean.

It’s not without some clever intervening that the tower has avoided a date with gravity. In fact, before it was even finished engineers battled to return the structure to an upright position.

We can all now breathe a sigh of relief, thanks to the latest survey of the bell tower, which found that its health is much better than forecasted. The tower has crept upright by about 4 centimeters (1.6 inches) in the 21 years since the last stabilization works were done.

The survey was conducted by a team of geotechnical engineers and funded by Opera Primaziale Pisana (O₽A), a non-profit organization established to oversee construction works to preserve the historic site.

“Considering it is an 850-year-old patient with a tilt of around five meters and a subsidence of over three meters, the state of health of the Leaning Tower of Pisa is excellent,” an O₽A spokesperson told Italy’s National Associated Press Agency (ANSA) earlier this month.

Construction of the Tower of Pisa began in 1174, and within a few years – following construction of its first few tiers in fact – it was obvious something was wrong. Its shallow foundations were constructed on an unstable base of mud, sand, and clay that was softer on the southern side.

Engineers tried to correct the lean as they went, making upper floors taller on one side than the other, resulting in what you could say is a marvelous building that’s curved as well as lopsided.

Over many years, with its tilt increasing, engineers attempted to sure up the eight-storey tower, sometimes making the problem worse. By the 1990s, the Tower of Pisa was no closer to solid ground, tilting 5.5 degrees to the south, just beyond the point at which engineers thought the tower would collapse.

Shortly thereafter, the tower was closed to the public and the Italian government enlisted a group of experts, chaired by civil engineer Michele Jamiolkowski, to work out how to save it. They thought about injecting cement beneath the tower but decided that was too risky and instead tried anchoring the north side down with 900 tons (816 metric tonnes) of lead weights to counterbalance the sunken south.

When that didn’t work, they excavated soil from beneath the tower’s north side. Slowly, it began to rise up – and rotate. Anyone who has played a gravity-defying game of Jenga would know how nerve-wracking that would be.

The decade-long stabilization project was eventually completed in 2001, after which the tower had straightened up some 40 centimeters and now its tilt is just shy of 4 degrees – still twice as much as the building’s original lean when construction finished in 1350.

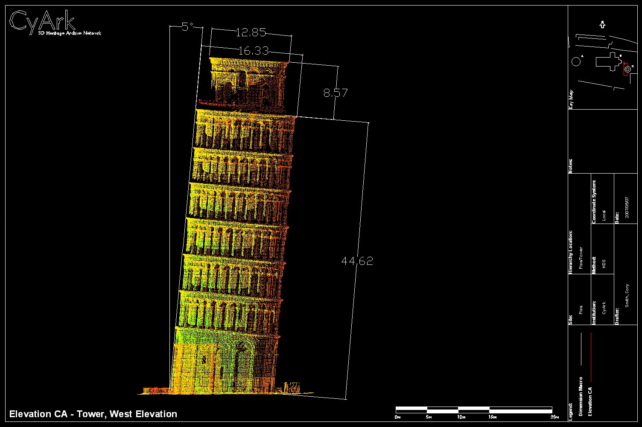

In 2013, researchers from Australia’s national science agency, CSIRO, also mapped every nook and cranny of the tower using 3D scanners, creating some ghostly digital reconstructions of the tower that could be used should the building ever need repairing.

Topple, hopefully, it will not. The tower now sways so slightly, oscillating on average around half a millimeter year, according to geotechnician Nunziante Squeglia, a professor of geotechnics at the University of Pisa, who is part of the monitoring group.

“Although what counts the most is the stability of the bell tower, which is better than expected,” Squeglia told ANSA.

In a country steeped in antiquity, Italy’s Leaning Tower of Pisa is not the only historic figure under close inspection for fear of collapse. Scientists have for centuries been eyeing off cracks in David of Michelangelo’s ankles that could bring down the world’s most perfect statue, an effort which ramped up after a 2014 paper found that a slight tilt of 5 degrees has already caused damage and could eventually lead to catastrophic failure. Earthquakes the same year didn’t help allay tensions.

While the fate of David is precarious, thankfully the Leaning Tower of Pisa should be secure for at least the next 300 years and maybe more, experts say. Some engineers even think that the restoration efforts could be so successful that the infamous tower may one day right itself.

Ironically, research shows that the same soft soils beneath the tower’s foundation that produced its characteristic lean might actually now offer some protection from earthquakes, giving the structure a longer, less destructive natural vibration period if rocked.

So perhaps a better question to ask ourselves is: will the Leaning Tower of Pisa ever stand up straight? And what then will become of its name?