Products You May Like

A new study has revealed that small lakes on Earth have expanded considerably over the last four decades – a worrying development, considering the amount of greenhouse gases freshwater reservoirs emit.

Between 1984 and 2019, global lake surfaces increased in size by more than 46,000 square kilometers (17,761 square miles), researchers say. That’s slightly more than the area covered by Denmark.

Carbon dioxide, methane, nitrous oxide, and other gasses are constantly produced from lakes, because of the bacteria and fungi feeding at the bottom of the water, snacking on dead plants and animals that have drifted down to the lake floor.

In total, this lake spread equates to an annual increase of carbon emissions in the region of 4.8 teragrams (or trillion grams) of CO2 – which to continue the country comparisons equals the increase in CO2 emitted by the whole of the UK in 2012.

“There have been major and rapid changes with lakes in recent decades that affect greenhouse gas accounts, as well as ecosystems and access to water resources,” says terrestrial ecologist Jing Tang, from the University of Copenhagen in Denmark.

“Among other things, our newfound knowledge of the extent and dynamics of lakes allows us to better calculate their potential carbon emissions.”

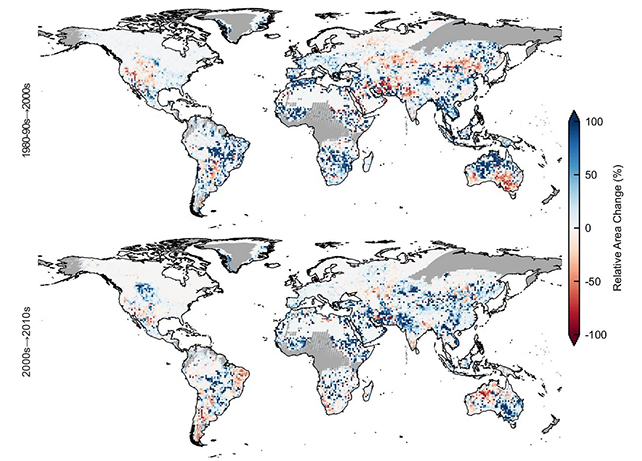

The researchers used a combination of satellite imagery and deep learning algorithms to make their assessments on lake coverage. A total of 3.4 million lakes were logged in total.

Smaller lakes (less than one square kilometer or 0.39 square miles) are so important to the calculation of greenhouse gases because they produce a high volume of emissions relative to their size, the team says.

These less expansive bodies of water account for just 15 percent of the total lake coverage, yet are responsible for a 45 percent of the increase in carbon dioxide output and 59 percent of the increase in methane emissions across the 1984 to 2019 period.

“Small lakes emit a disproportionate amount of greenhouse gasses because they typically accumulate more organic matter, which is converted into gasses,” says Tang. “And also, because they are often shallow. This makes it easier for gasses to reach the surface and up into the atmosphere.”

“At the same time, small lakes are much more sensitive to changes in climate and weather, as well as to human disturbances. As a result, their sizes and water chemistry fluctuate greatly. Thus, while it is important to identify and map them, it is also more demanding. Fortunately, we’ve been able to do just that.”

More than half of the increase in lake coverage over the study period is due to human activity, the researchers say – essentially, newly constructed reservoirs. The rest is mainly due to melting glaciers and thawing permafrost, caused by the warming of our planet.

The researchers are hoping that their data will prove useful for future climate models, with a significant chunk of greenhouse gasses potentially coming from lake surfaces as more melting and warming continues.

“Furthermore, the dataset can be used to make better estimates of water resources in freshwater lakes and to better assess the risk of flooding, as well as for better lake management – because lake area impacts biodiversity too,” says Tang.

The research has been published in Nature Communications.