Products You May Like

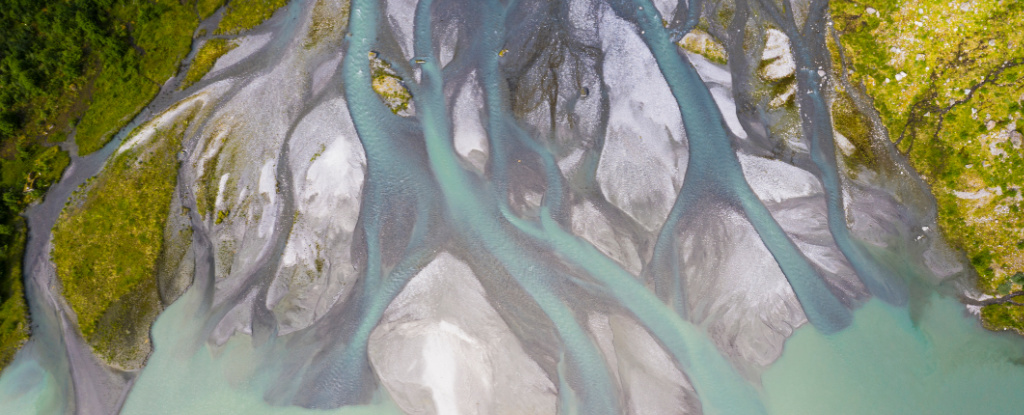

Fast-melting glaciers are releasing staggering amounts of bacteria into rivers and streams, which could transform icy ecosystems, scientists warn.

In a study of glacial runoff from 10 sites across the Northern Hemisphere, researchers have estimated that continued global warming over the next 80 years could release hundreds of thousands of tonnes of bacteria into environments downstream of receding glaciers.

“We think of glaciers as a huge store of frozen water but the key lesson from this research is that they are also ecosystems in their own right,” microbiologist and study author Arwyn Edwards of Aberystwyth University in the UK told the BBC.

Glaciers are masses of ice creeping ever so slowly toward the sea, carving out mountainous valleys as they go. Yet there is more to the flows than frozen water, with minerals, gases, and organic materials trapped on a one-way slide that could take tens of thousands to millions of years to terminate.

Studying the contents of glaciers is like opening the door to another time in history. Microbes entombed inside them could be a rich source of useful, new compounds, such as antibiotics. However, the researchers behind this new study say melting glaciers are releasing tonnes upon tonnes of bacteria faster than scientists can possibly catalog them.

Led by glacial hydrologist Ian Stevens of Aarhus University in Denmark, the team sampled surface meltwater from ten glaciers across the Northern Hemisphere: in the European Alps, Greenland, Svalbard, and the far reaches of the Canadian Arctic.

Finding on average tens of thousands of microbes in each milliliter of water, they estimate that more than a hundred thousand tonnes of bacteria could be expelled into glacial meltwaters over the next 80 years, not including the glaciers in the Himalaya Hindu Kush region of Asia.

That’s equivalent to 650,000 tonnes of carbon released per year into rivers, lakes, fjords, and oceans across the Northern Hemisphere, though it depends on how fast glaciers melt and how fast we curb emissions.

Under a ‘middle of the road’ emissions scenario – that would still see global temperatures rise between 2 and 3 °C – masses of bacteria in meltwater are predicted to peak within decades before declining or potentially disappearing entirely as glaciers recede, the researchers found.

“The number of microbes released depends closely on how quickly the glaciers melt, and therefore how much we continue to warm the planet. But the mass of microbes released is vast even with moderate warming,” Edwards said.

Earlier this year, scientists realized that Arctic ice is already thinning faster than expected. Other research suggests that some glaciers have already passed a tipping point where meltwater is slowing to a trickle as glacial runoff steadily declines.

Microbes in meltwater can fertilize downstream ecosystems, but these may be sensitive environments or catchments used by communities that depend on glacial runoff as a water source.

The researchers didn’t study individual strains of bacteria, only estimated their combined biomass, so they could not identify any species that might pose a threat to human health – nor did they determine whether microbes were active, dormant, damaged, or dead.

“The risk is probably very small, but it requires careful assessment,” Edwards told Steffan Messenger at the BBC.

Without further studies, we also don’t know how the sudden influx of microbes could contribute to further environmental change. Researchers expect it could have a profound effect on the productivity and biodiversity of microbial communities, as well as biogeochemical cycles.

On top of that, bacteria and algae found in icy environments usually contain pigments to shield themselves from damaging sunlight. But these pigments, in absorbing solar energy, could add to warming that is already accelerating glacial ice loss.

Although more research is needed to assess the downstream effects of glacial meltwater laden with microbes, these warnings shouldn’t be taken lightly. Humans’ thirst for water and unabated industrial activity has reshaped the global water cycle in ways we’re only just beginning to comprehend.

“Over the coming decades, the forecast ‘peak water’ from Earth’s mountain glaciers means we need to improve our understanding of the state and fate of ecosystems on the surface of glaciers,” says glaciologist and study author Tristram Irvine-Fynn at Aberystwyth University.

“With a better grasp of that picture, we could better predict the effects of climate change on glacial surfaces and catchment biogeochemistry.”

The study was published in Communications Earth & Environment.