Products You May Like

The Romans certainly knew what they were doing when it came to road-building, and new research shows that the routes they mapped out thousands of years ago are still linked to areas of prosperity today.

In other words, if you live close to the Roman road network established more than 2,000 years ago, you’re more likely to be in a comparatively wealthy area. The trade, profit, and development these roads enabled still matter in modern times.

That wasn’t the roads’ primary use originally; the ancient Romans built roads mainly to make it easier for troops to get around. Over time, the roads began to link towns and cities of significance.

“Given that much has happened since, much should have been adapted to modern circumstances,” says economist Ola Olsson, from the University of Gothenburg in Sweden.

“But it is striking that our main result is that the Roman roads have contributed to the concentration of cities and economic activity along them, even though they are gone and covered by new roads.”

At the peak of the Roman Empire’s expansion at the beginning of the 2nd century CE, some 80,000 kilometers (49,710 miles) of road had been established, with the first – a military supply route – starting construction in 312 BCE.

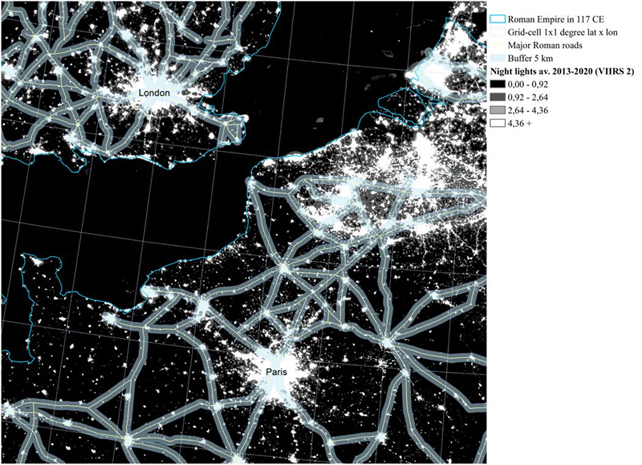

The researchers overlaid maps of the Roman Empire’s roads on top of modern-day satellite images, using night-time light intensity as an approximate indicator of economic activity. The map was divided into smaller grids for closer analysis, measuring a single degree of longitude by a single degree of latitude.

The team reports a “remarkable pattern of persistence” between Roman road routes and modern economic activity, despite much of the original infrastructure now having gone completely.

Whether the roads spurred economic activity or were built along routes that were already prospering remains – but there are indications that the former hypothesis is correct, that the routes drove an increase in trade and wealth. The emergence of market towns along the routes would have been crucial, the team says.

“That is the big challenge in this entire field of research,” says Olsson. “What makes this study extra interesting is that the roads themselves have disappeared and that the chaos in Western Europe after the fall of the Roman Empire would have been an opportunity to reorient the economic structures. Despite that, the urban pattern remained.”

The findings weren’t consistent everywhere, though: In North Africa and the Middle East, where camel caravans replaced wheeled transport sometime between the 4th and 6th century CE, the Roman roads weren’t built around or replaced.

In these regions, there’s no relationship between the old routes and current economic prosperity, and the areas are less prosperous economically overall. Again, the researchers say that the market towns – or in this case, their absence – are crucial.

The findings have implications for future infrastructure planning as well. Decisions about where to put road and rail routes have the potential to significantly improve the economic climate in a particular area – and as this latest study shows, that improvement can last for a long, long time.

“In Sweden, for example, we are talking about possibly building new railroad trunk lines,” says Olsson. “The former, from the 19th century, gained enormous importance for economic activity in Sweden. New stretches for the railroad are discussed, and if they are built you can expect some communities to get a big economic boost.”

The research has been published in the Journal of Comparative Economics.