Products You May Like

Cutting your own carbon footprint isn’t easy, even for the most motivated person. Tracking, tallying, investigating, researching.

For Sanchali Pal, though, that was part of the fun.

Pal, who had been working in international development, wanted to start trimming her footprint. “I started building an Excel spreadsheet of the carbon emissions in my life, starting with food, and it ended up becoming this massive spreadsheet and ended up using it over six years to lower my emissions by about 30%.”

Pal knew, though, that not everyone would go to those lengths. “I found it incredibly satisfying, but I’m a very particular kind of person.” Even still, she said the process was still “difficult and frustrating.”

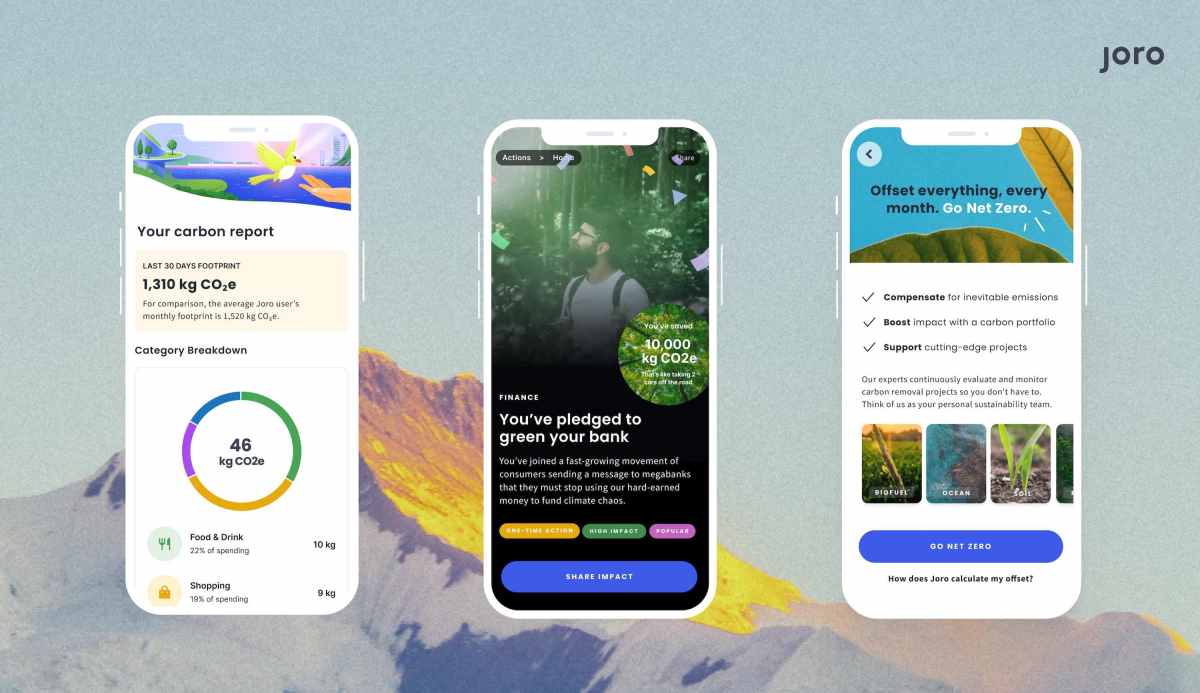

That’s what got Pal started on what would eventually become Joro, an app that helps people track and reduce their carbon footprints. Founded in 2018, Pal raised a $1 million pre-seed in 2019 and another $2.5 million in a 2020 seed round. Sequoia participated in both, leading the second round.

Image Credits: Cayce Clifford

Those investments have helped Joro triple its monthly active users over the past few months, reaching an average compound monthly growth rate of 25%. Now, TechCrunch has exclusively learned that Joro raised a $10 million Series A led by existing investors Sequoia Capital and Amasia. They were joined by Norrsken, Nest co-founder Matt Rogers’ Incite, Jay-Z’s Arrive, and Mike Einziger, the lead guitarist of Incubus.

The new funding will not only help build the Joro team, but it’ll also help continue the company’s shift from helping people track their footprints to helping them take action on what they learn.

While Joro users can get general advice on how to cut their carbon footprint, the real power of the app happens when the user connects their financial records, synced via Plaid. From there, Joro works to estimate their carbon footprint by studying payments and amounts, like how much spending happens at gas stations or on airfare, for example. From there, it offers more personalized suggestions for how the user might cut their own carbon footprint. (Pal said that Joro never sells this data outside the platform “and never will.”)

Sometimes those cuts are simple, like eating less meat, while others can be more challenging. For users with family scattered across the country, for example, eliminating air travel would be a difficult thing to ask. In that case, Joro then offers users the ability to offset their emissions.

For a fee, users can offset part or all of their emissions. To make it simple, Joro offers a subscription. For users on a budget, they can set a ceiling on how much they’re willing to pay per month. Most people using the app pay about $30 per month, Pal said. Some pay as little as $10, while others with more extravagant lifestyles pay as much as $1,000 per month.

Joro takes 17% of monthly subscription fees to help pay for the app’s services and — more importantly from the user’s perspective — for vetting offsets.

Finding high-quality offsets is incredibly challenging for individuals. I went down that path years ago and eventually gave up because the ones that I felt were suitably additional, verifiable and permanent were only available to large buyers. I didn’t want to be throwing my money after questionable offsets, so I didn’t buy any. Because Joro aggregates its purchases across users, it can buy the types that I couldn’t access on my own.

Pal said that Joro evaluates offsets every few months to ensure they’re living up to the company’s standards. In addition to the usual requirements — additionality, verifiability and permanence — the team also looks for what Pal calls “transformative potential.”

“How does this affect local ecosystems? Environmental justice considerations? Especially as a consumer, as a person, if you’re buying into offsets, things you might care about more than a company.”

The offsets cost Joro anywhere from $12 to $600 per metric ton. Some are nature-based solutions, while others are technological. The entire portfolio is balanced at an average of $25 per metric ton, Pal said.

The startup will use its new funding to build its team and continue the shift from tracking carbon footprints to helping people take action to reduce them. The new focus not only satisfies a frequent request from users — it also should open new opportunities.

“We think it could be another path to revenue, where people are actually changing things, switching to lower-carbon vendors or to lower-carbon ways of living. That’s a really great alignment of our impact model and our revenue model,” Pal said, saying that it would likely take the form of affiliate relationships between Joro and the vendors it features in the app.

Pal is optimistic that the new infusion of cash and recent growth trends will help broaden Joro’s impact. Already, though, she’s stunned by how the landscape has changed recently.

“Even three years ago, it was really hard to explain to people what Joro was,” she said. “The concept of climate tech barely existed, right? There was clean tech, and there was software. But software for climate? It’s been incredible to see how quickly it’s happened.”