Products You May Like

The discovery of incredible fossils of a giant marine lizard reveals how this ancient extinct beast would have ruled the sea 66 million years ago.

The beast is a newly discovered species of mosasaur, giant marine reptiles that hunted the oceans during the Late Cretaceous.

It’s called Thalassotitan atrox, and wear on its teeth along with other remains found at its excavation site suggest that this intimidating animal was no gentle giant – but feasted on difficult prey such as sea turtles, plesiosaurs, and other mosasaurs.

Other mosasaurs sought smaller prey, like fish, or ammonites (which weren’t actually always that small).

This means Thalassotitan likely occupied a spot at the very top of the food web, maintaining ecosystems by keeping the other predators in check.

“Thalassotitan was an amazing, terrifying animal,” says paleontologist and evolutionary biologist Nick Longrich of the University of Bath in the UK. “Imagine a Komodo dragon crossed with a great white shark crossed with a T. rex crossed with a killer whale.”

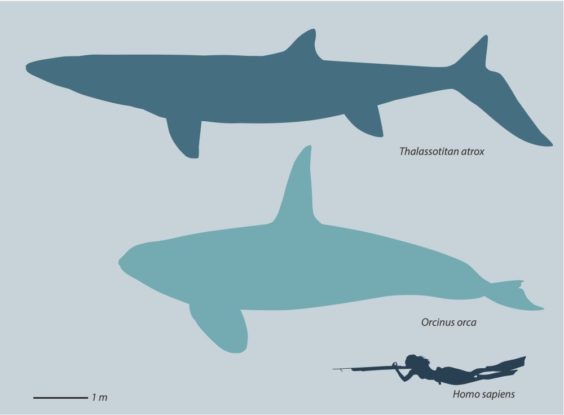

There is no reptile alive today that is on the scale of mosasaurs, which could reach lengths of 12 meters (40 feet) – twice the size of the largest modern reptiles, the crocodilians. But mosasaurs are related, instead and distantly, to modern snakes and iguanas.

Mosasaurs were better adapted to a fully aquatic lifestyle than the marine iguanas of the Galapagos. They had a reptilian head, but flippers instead of clawed feet, and a tail sporting shark-like fins.

Different mosasaur species could also specialize in different prey, given their different teeth. Some teeth were small and spiky, good for fish and squid; others had blunter teeth and crushing jaws, perfect for shelled creatures.

But, given that the animals don’t seem to have a good sense of smell, it’s likely that they were predominantly predators, rather than scavengers.

Analyses suggest that mosasaurs feasted on fish, cephalopods, turtles, molluscs, other mosasaurs, and even birds. Thalassotitan seems to have been among the fiercest.

The fossils were discovered in the phosphate fossil beds of Morocco, a region rich in diverse and excellently preserved Cretaceous and Miocene fossils.

The remains include skulls, vertebrae, limb bones, and phalanges. Together, they allowed for a complete description of Thalassotitan’s skull, jaw, and teeth, as well as the skeleton, shoulders, and forelimb.

The animal, Longrich and his team found, could likely grow to a length of around 9 to 10 meters – slightly larger than an orca. However its skull was nearly twice the length of the orca’s, coming in at around 1.5 meters long.

Unlike other mosasaurs which had slender muzzles, Thalassotitan’s jaw was wide and short, with large conical teeth that would have been perfect for seizing and rending prey. And these teeth contained another clue as to the animal’s diet: many of them are broken and worn, damage that would not occur from a diet predominantly consisting of soft prey.

According to the researchers, this suggests that Thalassotitan chipped and broke its teeth on hard surfaces, such as turtle shells, and the bones of other, perhaps more timid, mosasaurs.

This is supported by other fossils found near the Thalassotitan remains: the bones of large predatory fish, a sea turtle shell, a plesiosaur skull, and the bones of at least three different mosasaur species.

These remains all show signs of acid wear, as you might expect might occur in digestive acids in the belly of a giant beast, before being regurgitated back out. That is circumstantial evidence, the researchers note; but it’s still pretty interesting.

“We can’t say for certain which species of animal ate all these other mosasaurs,” Longrich explains.

“But we have the bones of marine reptiles killed and eaten by a large predator. And in the same location, we find Thalassotitan, a species that fits the profile of the killer – it’s a mosasaur specialized to prey on other marine reptiles. That’s probably not a coincidence.”

In the last 25 million years of the Cretaceous, mosasaurs became more and more specialized and diverse. The discovery of Thalassotitan suggests that mosasaurs were even more diverse than we thought – and that their ecosystem was alive and thriving, with enough prey diversity enough to support this predator diversification.

In turn, this has some interesting implications for the times leading up to the Cretaceous-Paleogene mass extinction 65 million years ago. It implies that, rather than declining and leaving the world vulnerable, as some have thought, biodiversity was going great guns, possibly in the wake of a smaller mid-Cretaceous extinction event.

More digging into the fossil beds of Morocco should clarify this intriguing possibility.

“There’s so much more to be done,” Longrich says.

“Morocco has one of the richest and most diverse marine faunas known from the Cretaceous. We’re just getting started understanding the diversity and the biology of the mosasaurs.”

The paper has been published in Cretaceous Research.