Products You May Like

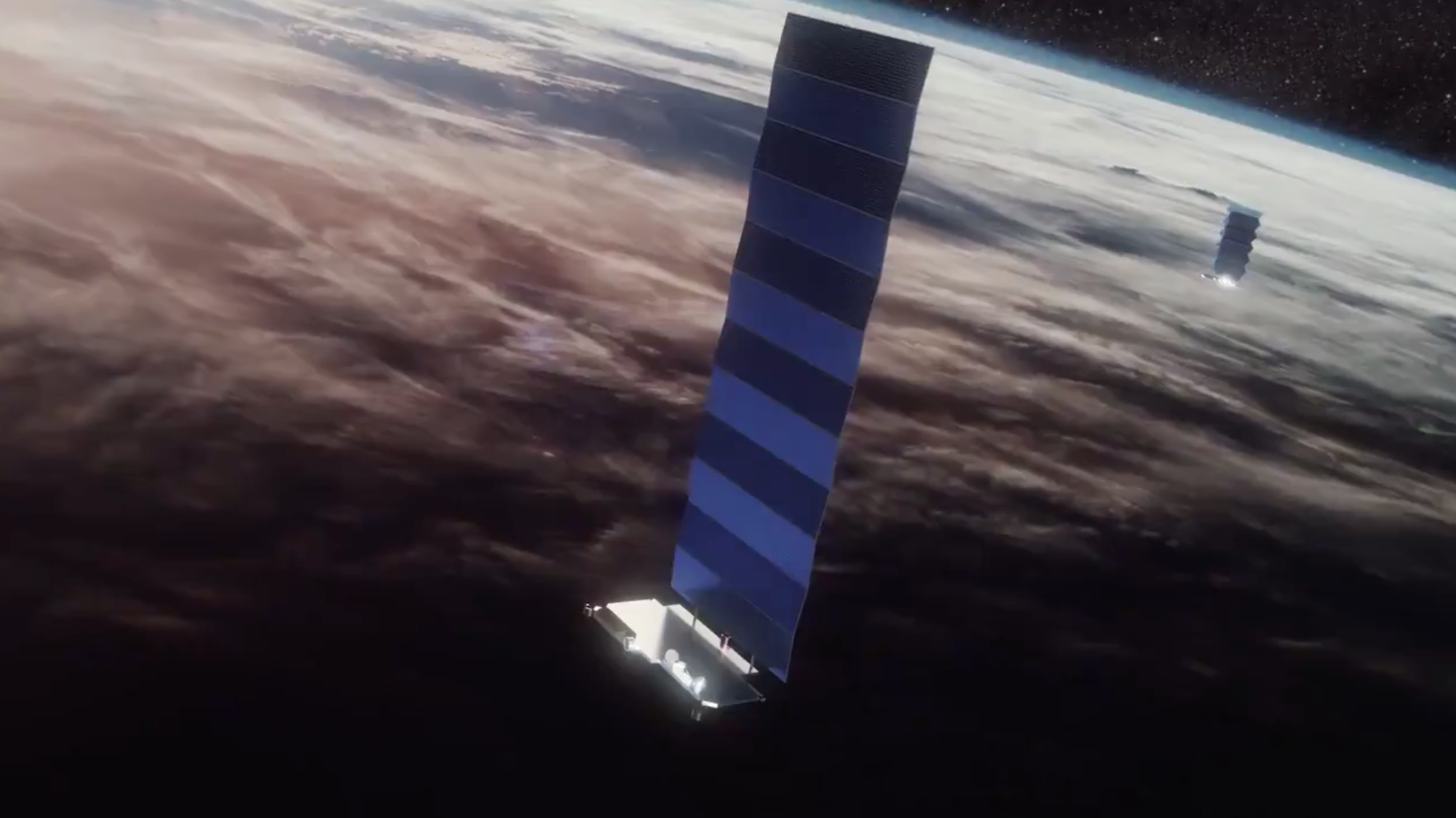

WAILEA, Hawaii — Two years after the close approach of a Starlink satellite with a European Space Agency satellite alarmed some in the space industry, SpaceX says it’s working closely with a wide range of satellite operators to ensure safe space operations.

In September 2019, ESA announced it maneuvered an Earth science satellite called Aeolus when the agency determined it would pass dangerously close to a Starlink satellite. The incident was exacerbated by a breakdown in communication between ESA and SpaceX in the days leading up to the close approach.

After that incident “we went to work coordinating” with both commercial and government satellite operators, said David Goldstein, principal guidance navigation and control engineer at SpaceX, during a panel discussion at the Advanced Maui Optical and Space Surveillance Technologies, or AMOS, Conference here Sept. 16.

The best-known example of that coordination is a Space Act Agreement between NASA and SpaceX announced in March. Under the terms of that agreement, SpaceX agreed to move its Starlink satellites in the event of any close approaches with NASA spacecraft, a move intended to avoid scenarios when both parties maneuvered their satellites.

In addition to that agreement, Goldstein said the company has a Cooperative Research and Development Agreement with the U.S. Space Force and a “good working relationship” with ESA and the European Union’s Space Surveillance and Tracking program.

Those partnerships extend even to OneWeb, a company that complained in Federal Communications Commission filings about a close approach one of its newly launched satellites had with a Starlink satellite in March. “We have a great working relationship with OneWeb after that conjunction in March,” Goldstein said. “Just fantastic coordination at the operational level.”

He specifically praised OneWeb for its support for the ongoing Inspiration4 crewed mission, saying “they jumped through a lot of hoops” to provide updated information about the orbits of its satellites. Goldstein appeared by video on the panel from SpaceX’s headquarters because, he said, he is providing collision avoidance support for Inspiration4, which launched Sept. 15 for what’s scheduled to be a three-day mission.

Other companies SpaceX is working with regarding space traffic management include Astroscale, which is developing technologies to service satellites and remove orbital debris, and United Launch Alliance. The work with ULA, he said, is to address “launch COLA [collision avoidance] sorts of issues.”

SpaceX recently signed a contract with LeoLabs, which provides commercial space traffic management services using data from a network of tracking radars it operates. “They’re doing great work, and we’re super proud of the accomplishments they’ve had and the help they’re providing to us and others,” he said.

Goldstein also expressed interest in Slingshot Beacon, a collaboration platform developed by Slingshot Aerospace to help satellite operators share space traffic information. That tool, he said, could make it easier for companies to share data and coordinate potential conjunctions.

One of the more controversial aspects of Starlink is its automated collision avoidance system, where the satellites maneuver 12 hours before the time of closest approach if the risk of a collision exceeds a set threshold.

Goldstein said he did not have up-to-date information on the number of such maneuvers the Starlink fleet has performed to date. However, he said the company informed the FCC that, from December 2020 through May 2021, Starlink satellites made more than 2,000 collision avoidance maneuvers.

“The average per satellite during that time is one to two,” he said. “That’s not a terribly high number for that many spacecraft.” SpaceX currently has nearly 1,700 Starlink satellites in orbit.

Goldstein appeared on a panel that was discussing developing “right of way” procedures for determining who should maneuver in the event of a close approach. “We need a sense of urgency to address things that we can do to avoid the Kessler Syndrome,” or a runaway growth of orbital debris. “There are things that we can do to make space safer, and we all need a sense of urgency to do what we can to avoid that.”