Products You May Like

Within the remains of 890-million-year-old microbial reefs – a world that was dominated by bacteria and algae – lie possible signs of multicellular animal life, 90 million years before there was thought to be enough oxygen in Earth’s atmosphere to sustain such life.

We all personally know oxygen is vital to us as animals – once inhaled, our respiratory systems pass the precious molecule to every corner of our body, so our cells can use it to make their chemical energy.

So it wasn’t known for certain whether multicellular animals (metazoans) could exist before Earth’s oxygen had reached the necessary level that allows this critical process of animal cellular respiration to take place. This milestone is generally thought to have occurred during the Neoproterozoic oxygenation event.

(Turner, Nature, 2021)

(Turner, Nature, 2021)

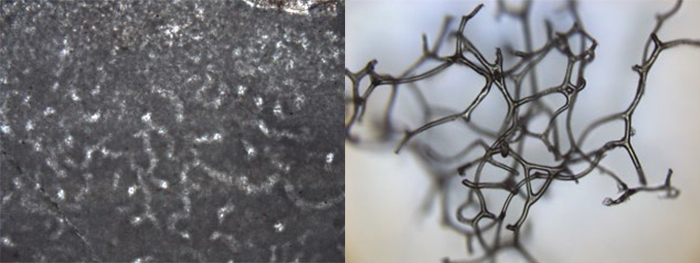

Above: Fossil pattern (left) compared to the pattern of a modern sponge skeleton (right).

Before this event, between 800 to 540 million years ago, dissolved oxygen in the oceans was probably too low to sustain metazoans – except near the reefs where oxygen-producing microbes dwelt.

But genetic evidence from animals contradict this. Molecular clocks suggest the Animalia kingdom of life started well back into the Neoproterozoic era.

Now, Laurentian University paleobiologist Elizabeth Turner has found potential fossil evidence to support this – within reefs that were once oases of oxygen.

Examining wafer thin slices of rocks from the Little Dal reefs in Canada with transmitted light micrography, Turner identified rare sections containing complex branching, 20-30 micrometer tubules, resting in gaps within and around the ancient reef formations.

The reefs were mostly built by photosynthesizing cyanobacteria and could reach kilometers in diameter, but the mystery structures were found on exposed edges, within depressions of the reef growth area and in shaded gaps.

This suggests that unlike the sunlight-seeking reef-builders, whatever formed the fossilized imprints didn’t need light but could withstand the exposure at the edges of the reef, and it also didn’t like to sit on the reef itself.

The fossilized pattern doesn’t match the branching seen in fungi and other microbes, or known geological patterns, but “closely resemble both spongin fiber networks of modern keratosan sponges,” Turner explains in her paper.

Example of a modern keratosan sponge. (Philippe Bourjon/Wikipedia/CC BY-SA 3.0)

Example of a modern keratosan sponge. (Philippe Bourjon/Wikipedia/CC BY-SA 3.0)

We have suspected for a while now that the dawn of the metazoans likely began with sponges – or something much like them – as they are the most basic known animals.

You’d be forgiven for thinking these strange creatures are more closely related to a cactus than a cat, given their weird vegetative-like morphology and sedentary existence.

They’re basically a perforated, soft-tissued sack, stuck to the ground on one end, that filters the water. But they, like us, produce sperm and eggs to reproduce, have cells that lack the cell walls found in plants, and their DNA firmly places them as an early relative to all other animals.

This fossil is “perhaps exactly what should be expected of the earliest metazoan body fossils,” writes Turner.

So far, the oldest undisputed sponge fossil is from the Cambrian, around 550 million years ago, but if this new find can be confirmed it suggests early animals emerged before oxygen conditions on Earth were optimal for us – and survived severe ice ages 720 and 635 million years ago.

We may all come from much tougher stock than we’ve realized.

Turner’s research is published in Nature.