Products You May Like

SAN FRANCISCO — Kleos Space is conducting a six-month test of technology for in-space manufacturing of large 3D carbon fiber structures that could be used to construct solar arrays, star shades and interferometry antennas.

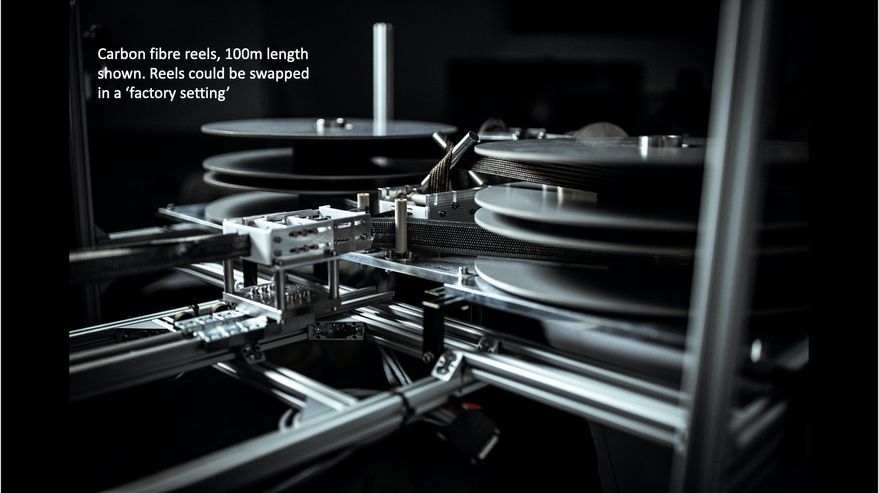

The company with operations in Luxembourg, the United States and United Kingdom is best known for radio frequency reconnaissance satellites. In the background, however, Kleos has been designing and developing in-space manufacturing technology called Futrism to robotically produce a carbon-fiber I-beam with embedded fiber-optic cables that is more than 100 meters long.

“It’s something that we have linked to our roadmap for RF, because it’s something that could deploy very large antennas for RF reconnaissance,” Kleos CEO Andy Bowyer told SpaceNews. “However, it’s useful for a whole range of other applications as well that we are very keen to work with partners on. We firmly believe that manufacturing in space is the future.”

In fact, the technology was not conceived with RF reconnaissance in mind. Bowyer and Kleos-co-founder Miles Ashcroft began focusing on in-space manufacturing at Magna Parva, a U.K.-based space engineering firm the pair co-founded in 2005. When Kleos spun out of Magna Parva, it took possession of the in-space manufacturing technology and intellectual property, which became part of the firm’s long-term technology roadmap.

That work continued as Kleos built a business around delivering data from clusters of four RF reconnaissance satellites flying in formation. The firm’s first cluster launched in November. Two additional clusters are scheduled to reach orbit this year.

Meanwhile, Kleos is continuing ground-based testing of an engineering model of its robotic manufacturing technology. Kleos modified pultrusion technology, a popular method for composite manufacturing on the ground, for use in space. The Kleos machine continuously pulls carbon fiber through a die, injects resin into the die and heats the material to produce cured I-beams.

“We’re making the equivalent of trusses for bridges and building blocks,” Bowyer said. “This is civil engineering on a massive scale for space applications.”

Kleos is now publicizing its work because of growing interest among government agencies and companies in manufacturing large structures in space. Government agencies and companies around the world have developed technology for on-orbit 3D printing, spacecraft robotic arms and in-orbit servicing. By combining all those components, complex systems could be manufactured and assembled in space, Bowyer said.

DARPA signaled its interest in “pioneer technologies for adaptive, off-earth manufacturing to produce large space and lunar structures” in February when the agency unveiled its Novel Orbital and Moon Manufacturing, Materials and Mass-efficient Design program.

Pultrusion is widely applied on the ground to manufacture products like aircraft components and sports equipment with tailored material properties. On the ground, though, machines rely on human support and maintenance as well as gravity to pour resin into the die.

A couple of major challenges for Kleos engineers were automating the entire process and devising ways to move fluid in microgravity especially after long-term storage.

Now that the engineering model works, Kleos is considering ways the technology could be deployed.

“If you can physically connect deployed and distributed sensors with fiber-optic cables, for instance, the position of those sensors are very accurate in relation to each other,” Bowyer said. In addition, the technology could pave the way for kilometer-scale reflectors to support science, he added.

Beyond Kleos, Bowyer envisions many applications for lengthy structures with embedded power and data cables.

“You would not just build large structures, but large structures that are intelligent, that can carry sensors,” Bowyer said. “We have a lot of ideas. But it’s a technology that has a life way beyond Kleos’ needs that is really exciting.”