Products You May Like

I am fully aware that I am in the minority on this, but in my opinion Scream 4 is the best film of the series. There is certainly tough competition. Scream is one of the more consistent franchises in horror, largely due to the remarkable continuity of talent it has enjoyed both in front of and behind the camera. The original film is a landmark in horror cinema, a foundational shift in the landscape that changed the face of the entire genre. Its greatness cannot be denied and certainly will not be by me. Scream 2 upped the ante and remains one of the all-time great sequels and, though generally not as highly regarded as the other films in the series, Scream 3 certainly has plenty of fans.

I will contend, however, that Scream 4 takes everything that is great about the original film and at least attempts to outdo it. More often than not, it succeeds. The film continues the stories of its legacy characters in logical and interesting ways while also introducing compelling new characters. It expands on the themes and mythologies of the previous films while acknowledging the fact that much had changed in the fifteen years since the original and eleven since the previous entry. It also introduces an element that had not been present in the previous films, social media, and presents what has turned out to be very prescient exploration of its dark side.

Finally, Wes Craven continually challenged himself, grew as a filmmaker throughout his four-decades in the industry, and channeled all of that knowledge and energy into its making.

Neve Campbell, David Arquette, and Courteney Cox return to their characters with such ease and familiarity. Because of the eleven-year gap between the third and fourth films, there is a sense of renewed enthusiasm and an electricity to their performances. Sidney Prescott returns as a woman intent on escaping her identity as a perpetual victim, having written a book on the subject. Though seen by the teenagers of Woodsboro as “the Angel of Death” this is clearly not who she is, but a fighter and a survivor. Dewey and Gale have been married for ten years and Gale has given up her journalism career to support her husband, who has become Sheriff of Woodsboro. Clearly this has created tension in their relationship. When the murders begin, Gale finds a renewed sense of purpose and hopes that she and Dewey can recapture some of the magic they once had.

The familiarity with these characters from writer, director, and actors as well as a shared history gives a new depth and pathos to the writing and performances. Their interactions contain genuine tension, affection, and chemistry as necessary for the situations. The relationships are more complex and nuanced than they ever have been before and the three actors certainly rise to the challenge. For me, they even top their performances in the original film. Also, because screenwriter Kevin Williamson had grown as a writer, there is an even deeper realism to these three and all the characters in the film than had ever been present before.

Surrounding the familiar characters from the previous films, Williamson created a new cast of supporting characters as compelling as any in the series. Sidney’s cousin Jill (Emma Roberts) is the connective tissue for her friends, Olivia (Marielle Jaffe) and Kirby (Hayden Panettiere), and ex-boyfriend Trevor (Nico Tortorella) to the legacy characters. Film geeks Charlie Walker (Rory Culkin) and Robbie Mercer (Erik Knudsen) serve as stand-ins for film-Twitter and offer a bit of meta-commentary on the character of Randy Meeks played by Jamie Kennedy in the previous films. This group of teenagers are the most compelling new characters in the film. Their relationships feel organic and natural, I would argue even more so than among the teens in the original film. Added to the adult cast are Marley Shelton as Deputy Judy Hicks, a controversial character to be sure, Anthony Anderson and Adam Brody as members of the Woodsboro police force, and Oscar nominee Mary McDonnell as Sidney’s aunt.

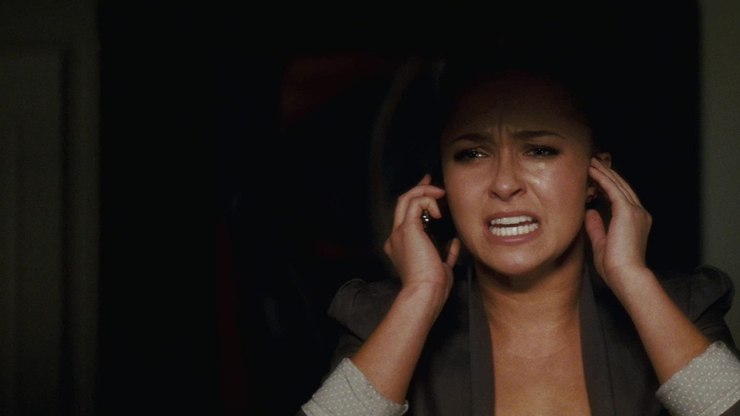

Of all the new characters, however, Kirby Reed was immediately embraced by horror fans. She is the embodiment of the fact that horror had entered the mainstream, at least in part thanks to Scream. She is smart, popular, beautiful, and knows at least as much about horror movies as Charlie and Robbie. She is the one character to ever beat Ghostface at his quiz game, only to be double-crossed and stabbed in the stomach. In recent years, the slogans “Justice for Kirby” and “Kirby Lives” have been floating around in hashtags and on t-shirts. Many fans hold out hope that she will against all odds return in the fifth Scream movie. To be fair, we don’t actually see her die in Scream 4 and stranger things have happened in the Scream universe (long lost brother, anyone?).

Like its predecessors, Scream 4 is certainly a commentary on the state of horror at the time of its release. The aughts were a time of so-called “torture porn” and a massive boom in remakes of horror classics of the 70’s and 80’s. Each of the Scream films is well known for its cold open. Here, the opening sequence comments on sequel culture watering down the original, but this had been well-covered ground in Scream 2 and 3. The double opening subverts this, even commenting in the dialogue before a surprise kill that “you can see everything coming.” The triple opening takes us into uncharted territory, even for the Scream franchise. Just as Wes Craven’s New Nightmare (1994) was a commentary on the success of the Elm Street films, Scream 4 not only examines the horror remake boom, but specifically the success of the Scream movies through its on-screen stand-in Stab. In this film, the Stab series has veered off course into every bizarre trope of the slasher sequel imaginable including time travel, Facebook killers, and “meta-shit.” Scream 4 pokes the eye of the many Scream imitators but also realizes that Scream itself is not above some self-directed satire. The cold open is a prime example of that fact.

Yes, the movie is a meta-commentary on horror sequels, remakes, and even meta-horror itself, but its most pointed commentary is about something far more applicable to 2021 than it was upon its release ten years ago. In 2011, social media was generally considered to be innocuous. It was about connecting with old college friends, sharing opinions about the latest episode of The Bachelor, and posting low-res pics of last night’s dinner. But Williamson and Craven saw much darker possibilities lurking below the surface. The film uses social media as a method of deconstructing the nature of fame in the age of Facebook, Twitter, and now Instagram, where personal worth is measured in likes, retweets, and follower count.

Jill’s motive may be the most compelling of any in the Scream films because it is really no motive at all. And as we learned from the first film, “it’s scarier when there’s no motive.” She seeks only notoriety, fame, and fans. “My friends? What world are you living in?” she tells Sidney, “I don’t need friends. I need fans.” Jill’s monologue has turned out to be frighteningly true. “Look around. We all live in public now, we’re all on the Internet. How do you think people become famous anymore? You don’t have to achieve anything. You just gotta have fucked-up shit happen to you.” How many names of killers do we know because of social media posts shared on national news? How many atrocities have been committed by “nobodies” seeking any kind of attention they can get? How many of their “manifestos” have been published and spread through social-networking sites? This foresight into the dark underbelly of social media may well be the greatest reason for the reevaluation of Scream 4 in recent years. Unfortunately, it has turned out to be far-too prophetic.

In a less overt way, the film delves into the popular true crime trend, specifically the consumption of true stories of murder and tragedy as entertainment. In reality, this is nothing new. Horror films and stories have drawn inspiration from true events since the beginning. What Scream 4 asks is “where do we draw the line?” At what point have we crossed into the lionization of evil people and the exploitation of victims and survivors? Maybe that particular genie is already out of the bottle and the question needs to be, “where do we go from here?” Like many of Craven’s best films, the questions are presented but left to the viewer to answer. The questions are not judgements or condemnations but true inquiries that deserve thought, discussion, and debate.

Wes Craven’s films have often proven to be incredibly insightful and even ahead of their time. As far back as The Last House on the Left (1972), Craven had been able to tap into elements that audiences found simultaneously repellant and compelling. He continually worked at honing and refining his abilities as a filmmaker and storyteller and never settled for taking the safe route in his work. He fundamentally changed horror three times in his career with Last House, A Nightmare on Elm Street (1984), and Scream (1996). Had it been more successful on its initial release, perhaps Scream 4 could have been a fourth time. It is a remarkably daring film in many ways. It is highly subversive, insightful—even prophetic, and as with most Craven films, politically and intellectually astute. But it is also the fourth film in a series and sequels are rarely taken as seriously as the original.

Though Wes Craven rarely got to make films entirely as he envisioned, he did always remain true to what interested him most and this film is no exception. It is gratifying to see the cult of this final film from one of the true masters of horror grow over time. In the ten years since its release, the power of its story and themes as well as the great craft in its making have all contributed to this. Scream 4 has proven in the years since its release to be a fitting capstone to a remarkable career.